‘The Godfather’ celebrates 50 years as the ‘greatest family movie ever’

Classic Mafia film resulted from ‘a series of miracles’

As The Godfather celebrates its 50th anniversary this month, the movie is regarded as one of the best ever made, a Mob classic centered on timeless themes of family, loyalty and justice.

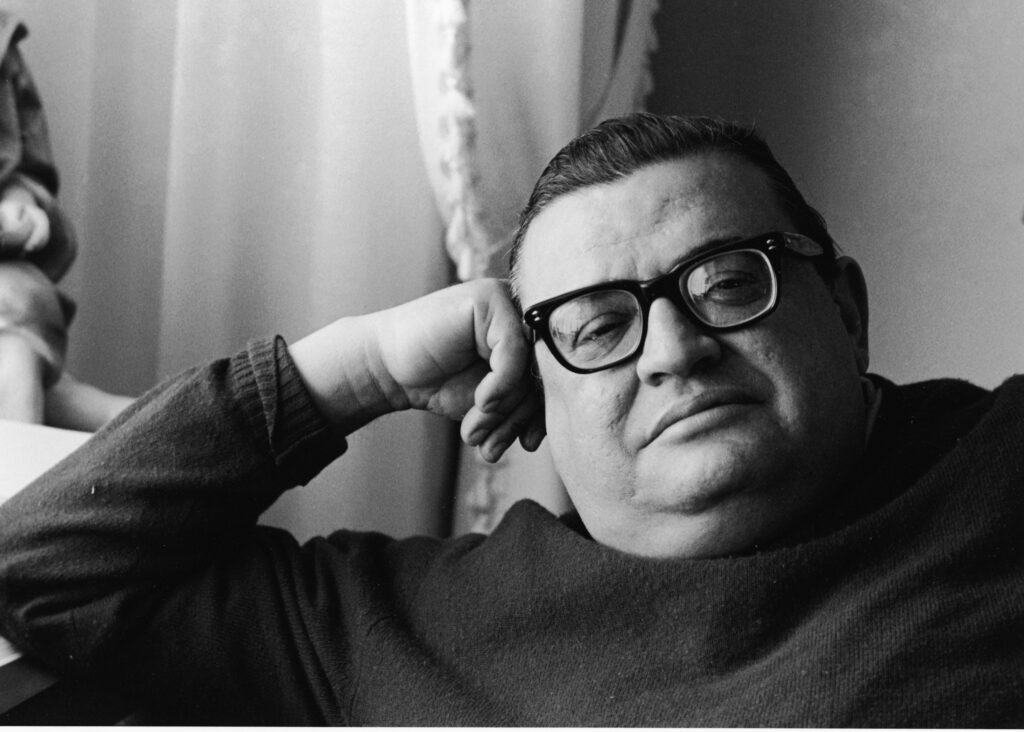

The novel came out three years before the movie was released. Written by Mario Puzo, it is a fictional tale of a New York Mafia don and his empire. It was popular from the start, selling nine million copies during its first two years on bookstore shelves. Since then, the novel has sold millions more.

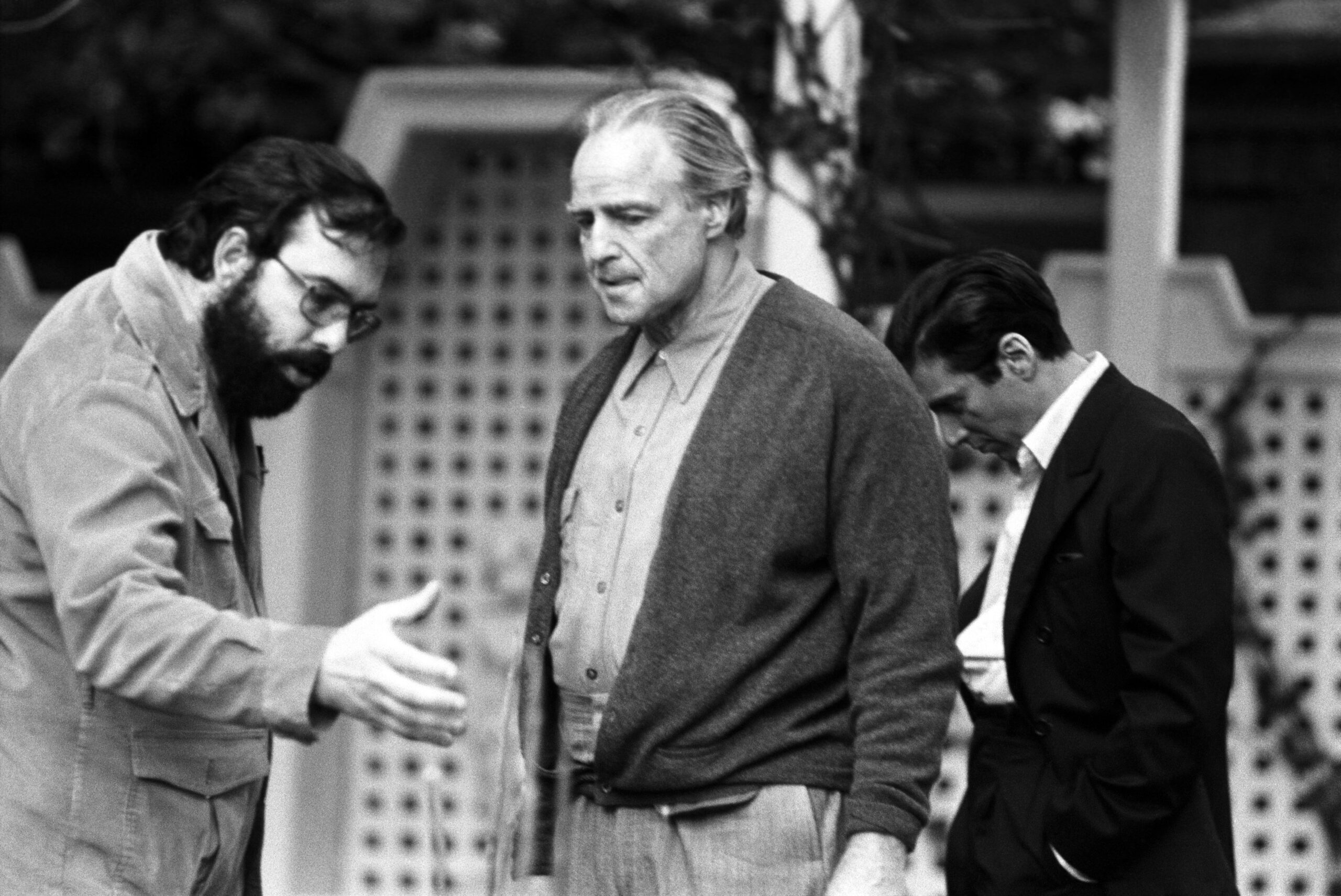

The names associated with the novel and movie, including Puzo and director Francis Ford Coppola, are widely recognized today, having transformed Puzo’s imagined underworld into three Godfather movies, the first appearing in March 1972.

In the beginning, however, executives at Hollywood’s Paramount Pictures had little faith in the creative team’s ability to pull off a marketable movie, much less a masterpiece.

Don’t miss The Making of The Godfather: The 50th Anniversary of a Mob Masterpiece on Wednesday, March 16

This program will explore the making of The Godfather with actor Johnny Martino, who played Paulie Gatto. The discussion also will dig into the real-life Mob’s involvement with the film.

Surprise success

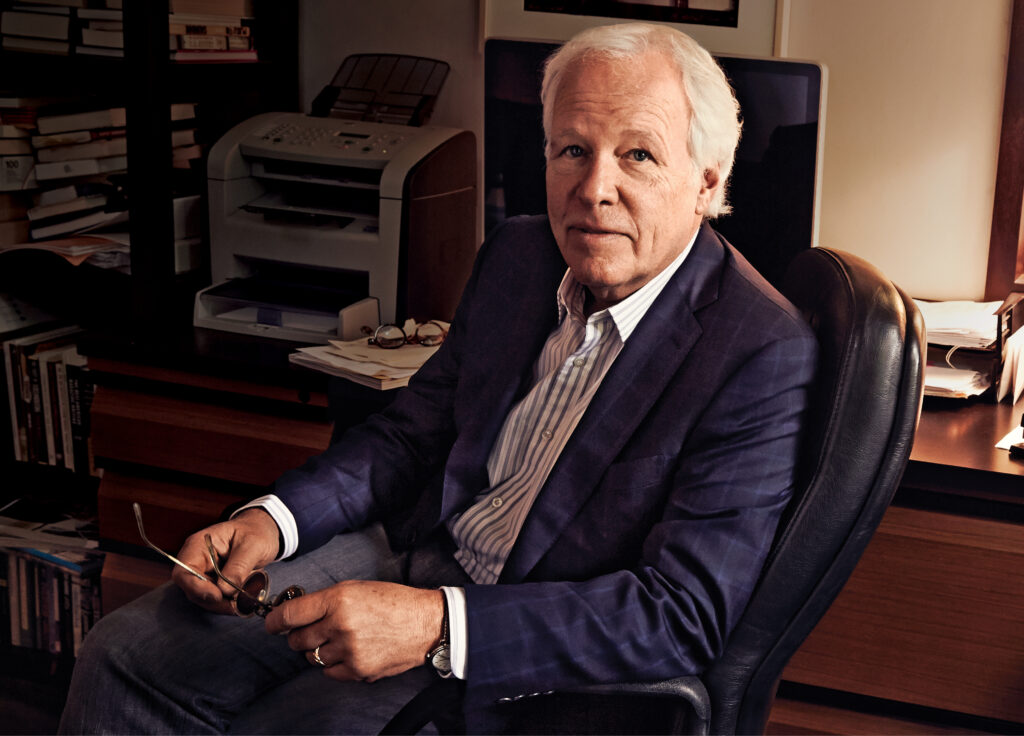

Faced with obstacles at every turn, The Godfather “is the result of a series of miracles” that led to the movie’s 1972 debut, according to journalist and author Mark Seal. Seal is the author of Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli: The Epic Story of the Making of The Godfather, published in 2021.

As the book points out, Puzo himself was a surprise success.

Before making a splash at age 48 with his blockbuster novel, the former Army private, a compulsive gambler with a large family to feed, churned out lurid stories and adventure tales for mass-market publications. One of these stories, published in Male magazine, focused on a Hawaiian gangster and “the ultimate in hot-fleshed women and cool-chip gambling.”

Puzo had published two obscure literary novels, earning a few thousand dollars combined. The other writing job for men’s magazines helped him stay afloat. In his 1976 nonfiction book Inside Las Vegas, Puzo, whose favorite Southern Nevada casinos during his flush years included the Sands and Tropicana, wrote about an earlier period in his career when he had to move with his wife and children into a new Bronx housing project. At the time, Puzo’s obsession with gambling frequently left him in a deep financial hole, but it paid off a time or two.

“It cost $85 to move,” he wrote. “I only had $20. I bet the $20 on a baseball parlay taking two underdogs with big odds. I won. I didn’t have to borrow the money. I kept my pride.”

Puzo’s early struggles as an author came as one of the biggest surprises to Seal when researching and writing the book.

“I had read about his gambling and indebtedness, but didn’t know the extent of that until I read some of the letters he had written asking for extra time to pay various bills, which are included in his papers at Dartmouth College,” Seal said in an email.

‘Going places’

Coppola had not done much better at first. Though he had success as a screenwriter, winning an Oscar for co-writing the World War II movie Patton, Coppola was not a prominent filmmaker. His early experience as a director included work in the 1960s sexploitation industry, where films were called “nudies.”

Marli Renfro appeared in one titled Tonight for Sure and saw promise in the young Coppola. She later had a role in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho as Janet Leigh’s body double during the shower scene. In an Esquire article recalling those years, she spoke fondly of Coppola.

“He reminded me so much of Hitchcock, just the way he did things, the way he directed me,” Renfro said. “I remember thinking at the time, ‘This young man is going places.’ He was so methodical and knew exactly what he wanted and was just very creative.”

Until Coppola hit it big, some in Hollywood didn’t see him on the same level as Hitchcock.

When The Godfather was being cast and filmed, the studio was struggling, led by meddling executives who pinched pennies and planted a spy on the set. Real Mafia members protested during filming, claiming the movie would stereotype Italian Americans.

Except for Marlon Brando, who was thought to be problematic and washed up, the other actors were not well-known. A studio executive described Al Pacino, because of his short stature, as “a runt.” Pacino lost sleep, worried about being fired. Coppola, already concerned he would be replaced, was undercut and betrayed along the way. At one point, a mountain of worries caused his frustration to boil over.

“One night, after another hellish day of filming, he returned to his borrowed apartment, passing his pregnant wife, two young sons, and other family members and headed into the bedroom,” Seal wrote in Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli. “He stripped the blanket off the bed and started furiously tearing. Rip, rip, rip, until the blanket was in shreds and he collapsed on the naked bed.”

Combined, the people working with Coppola to pull The Godfather together represented the “unlikeliest of teams in a movie that few believed would succeed, much less sweep the world,” Seal said.

“Its author, Mario Puzo, was usually broke and saddled with sizable gambling debts,” Seal said. “Its studio was on the brink of collapse. Its director had just turned 30 and accepted a job that most bankable directors had turned down. Coppola took it because he needed the money.”

Seal said the cast was “comprised of almost unknowns” — James Caan, Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton and John Cazale.

“Its leading man, Marlon Brando, at 47, was considered a has-been and box-office poison,” Seal said. “Against those odds, which no Las Vegas casino would take today, The Godfather endures, fifty years later, as perhaps the greatest movie ever made.”

Family first

Looking back, many credit The Godfather’s popularity with its focus on the patriarch, Don Vito Corleone (Brando), and his family.

In Seal’s book, the movie’s producer, Al Ruddy, says, “There is one reason that movie is successful and one reason only. It may be the greatest family movie ever made.”

Having this family life at the center of the movie gives The Godfather its “heart and soul,” Seal said. “In creating the Corleone family, Mario Puzo in his novel and Francis Ford Coppola, who directed the film and co-wrote its screenplay with Puzo, created a family of gangsters, not merely as criminals and killers, but as family men.”

Puzo’s own family shaped his work. He grew up in the rough Hell’s Kitchen section of New York City.

“Even though Puzo would say he had never met an actual gangster when he wrote his novel,” Seal said, “he came from a strong Italian American family with a strong Italian American mother, who wielded language like a weapon and, Puzo said, first uttered some of the famous lines he would give to Don Corleone, including, ‘A man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man.”

Seal’s favorite Mob productions are the first Godfather film, followed by The Sopranos, Goodfellas, Casino and The Irishman. “All of them embrace their subjects as family first, criminals second,” Seal said.

Mob movies and shows like these continue to generate interest because they are “the new American Western,” he said.

“In the book,” Seal said, “I quote the media scholar Robert J. Thompson, who wrote in the 2002 reissue of Mario Puzo’s novel, The Godfather: ‘The Western has been replaced by the Mob story as the central epic of America.’”

Included in this is “an unbreakable code, a solid sense of family, and an ability to bypass bureaucratic loopholes and inefficiencies,” according to Thompson. “These people could get things done, and while some of those things were horrible, most of their victims deserved what they got and were usually outlaws themselves.”

A seat at the table

At age 82, Coppola continues to focus on his work, including a project titled Megalopolis. The new project “remains something of a mystery,” according to Variety, but could turn out to be a sort of Roman epic, “set in a utopian version of New York City called New Rome.”

For Godfather fans, there is more to look forward to. On April 28, Paramount+ is planning to debut The Offer, a 10-episode series looking at Ruddy’s experiences in producing the movie.

As this upcoming series indicates, people are still fascinated by the underworld that Puzo dramatized in his 1969 novel. After the book came out, Puzo did not slow down. For years, he continued writing novels and screenplays. By the time he died in 1999 at age 78, he had become a celebrity author, featured on the covers of Time and New York magazines, earning recognition seldom granted to literary figures.

That recognition was a long way from his job writing potboilers and adventure tales for the Magazine Management company in his hometown, New York City.

Magazine Management’s editorial director, Bruce Jay Friedman, later an acclaimed author himself, said its writers “seemed not so much to have been hired as to have washed ashore at the company like driftwood.”

“We were all slightly ‘broken’ people,” he wrote in Lucky Bruce: A Literary Memoir. “A few had gifts, but we were ‘rejects’ all, having clearly been unable to cut the mustard at the Luce and Hearst empires.”

Puzo was one who ultimately broke through. A hint of this ascent occurred one night in 1966 during a dinner at the Long Island home of writer Gay Talese’s aunt, Susan Pileggi. Talese during this period was a New York Times reporter, and his friend Puzo was working on the The Godfather novel-in-progress. One of Puzo’s earlier novels featured a minor Mob character. An editor suggested Puzo play up the Mafia in future work.

In Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli, Seal captures the significance of this dinner.

“That night, assembled at the table, sat the future of Mob literature: Talese, who would write the organized crime classic Honor Thy Father; his first cousin Nick Pileggi, who would write Wiseguy (the basis for the film Goodfellas); and Puzo, who was in the process of writing The Godfather.”

Gay Talese’s wife, Nan, was there, soon to become “a celebrated publisher of some of the greatest authors of her time,” Seal wrote.

Seated with members of the Talese and Pileggi families, Puzo was beginning his rise to the top, based on a fictional family of his creation, the Corleones.

In this transition from a world of literary “rejects” to dinner with “the future of Mob literature,” Puzo had found his place at the table.

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. The Mob in Pop Culture blog appears monthly.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org