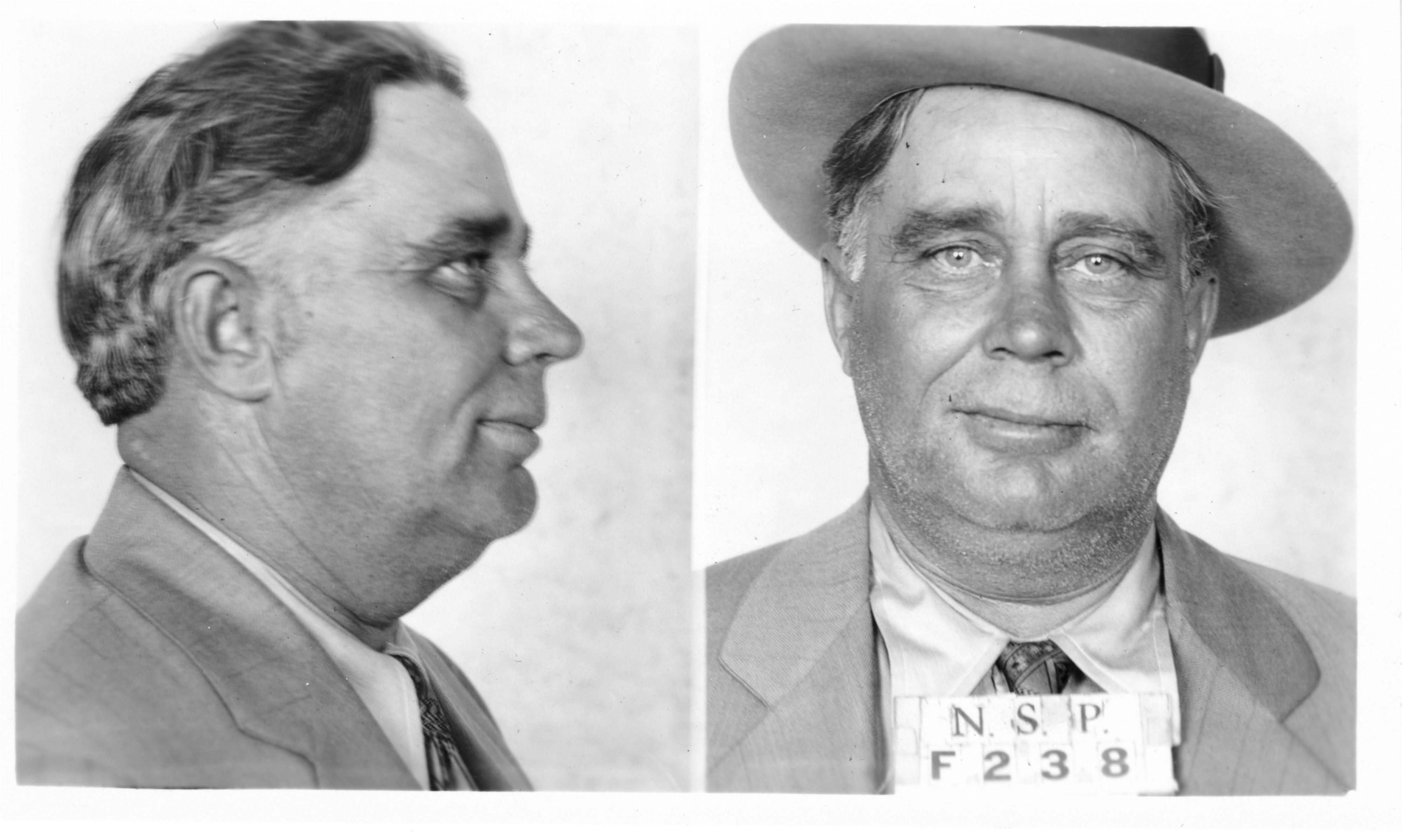

The first mobster in Las Vegas: Part 1

Las Vegas crime kingpin Jim Ferguson reigned over city’s bootlegging, vice rackets during Prohibition

First of three parts

In the 1920s and ’30s, the U.S. government considered him a “menace to society.” Nevada law enforcement officers said he led “one of the most dangerous gangs of criminals operating” in the state. And, in Las Vegas, he had the title “King of the Tenderloin.”

Meet Las Vegas’ first organized crime figure, James “Jim” Ferguson. During his reign in Nevada, Ferguson left a trail of destruction, from death to political corruption, robbery, burglary and bootlegging.

Little is known about the first 30 years of his life. He once told prison guards he was born January 9, 1893, in Memphis, Tennessee. With the scars of two bullet wounds on his stomach when arrested, he told jailers, “I am a farmer.”

In 1924, as he turned 31, Ferguson arrived in Ely, Nevada. At the time, in most of the United States, gambling, prostitution and the sale of alcohol were illegal. The same was true in Nevada, but many residents considered the state wide open to tolerating vice rackets. And Ely was at the top of the wide-open list.

Like Las Vegas, Ely, incorporated as a city in 1907, was still a new town. And like Las Vegas, its work force was in large part made up of single men. With massive copper mines feeding its economy, Ely was much larger than the railroad maintenance town of Las Vegas.

However, when Ferguson arrived in Ely, he soon found out there was little opportunity for someone with his skills. The city’s leaders and vice lords had already come to an accommodation.

Ferguson did make contacts in Ely’s so-called “restricted district.” He met Vera Magness, who worked in the “district” and wanted to set up her own brothel. She would soon become the common-law Mrs. Ferguson.

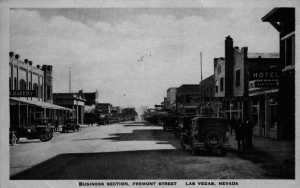

The two headed to Las Vegas. After arriving there in late 1924, Ferguson found gambling, legal and illegal, prostitution and bootlegging all flourishing. At the time, Las Vegas’ population was about 2,300.

The young Ferguson learned that those in charge of the city’s red light district had been in control for nearly two decades. They appeared vulnerable to a takeover.

As for the local police, they were concerned primarily with keeping traditional criminals out of town.

Ferguson decided the environment was ripe for the picking and began working on taking over. He received some unexpected help. A local grand jury had just been empaneled and was looking at ways “to clean up the present very unsatisfactory moral condition” of the community. On February 5, 1925, the Clark County Grand Jury issued its report on the state of the local society. It provided Ferguson with an outline of the weaknesses in the area’s criminal justice system.

The panel criticized Clark County’s law enforcement, from the sheriff’s office to the city police for the “almost total non-enforcement” of the laws prohibiting the sale of liquor. The Las Vegas Age newspaper was of the opinion that “a careful reading impresses one with the idea that the present grand jury has determined that conditions in Clark County in respect to morals and the bootlegging evil shall be improved.”

The grand jury also went after gambling, calling it “one of the most pernicious vices, demoralizing in its effect and which brings into a community an undesirable element.” All levels of government must make “a concerted effort to clean up the present very unsatisfactory moral condition in our county.”

Not long after the grand jury released its report to the public, the city prepared for an election. The office of mayor and four seats on the City Commission would be on the ballot.

With the grand jury report still a matter of discussion, candidates had to center their campaigns on morality in civic life. The incumbent mayor, William German, seeking re-election, emphasized efforts to halt bootlegging and his promise to improve the standards of decency within the community.

German called the bars, brothels and gambling dens tolerated by the city “a brazen temptation to the susceptible.” He called on the voters to elect those “who will have the courage and backbone to work with me in controlling and regulating the open vice conditions that are a disgrace to our city.”

The mayor’s opponent, Fred Hesse, replied, “Much is being said about the morals of our city. I intend, if elected, to put forth every effort to correct existing evils.” However, Hesse added that he would enforce the laws with a balance of “sanity as well as to decency.”

From the beginning of Las Vegas’ city government in 1911, the elected city commissioners not only set policy, but each commissioner would directly control a municipal department.

The mayor had the power to make the appointments. One commissioner would be in charge of the city police, another the streets, another the lights and sewers and the fourth the city’s finances.

Of the 941 votes cast, Hesse beat German by a slim margin of 38.

In the wake of the city elections of 1925, Ferguson had emerged, one newspaper put it, as “a power in the underworld of Las Vegas.” Magness, as Mrs. Ferguson was known, opened a brothel in Block 16, the red light district. Ferguson was poised to make his move to become the “King of the Tenderloin.”

Up to that point, only one person stood in his way: Al James. For nearly 20 years, James was the titular leader of the local red light industries. James owned and operated the Arizona Club, the largest saloon and gambling hall in Las Vegas, located at the center of Block 16.

Block 16 was the 16th block in the grid laid out by the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad when it auctioned off its land within the Las Vegas Township in 1905. One of the railroad’s stipulations in the deeds from the land sale focused on the sale of alcohol. Only in Blocks 16 and 17 could the retail sale of alcohol be the primary function of a business.

The deed restriction did not hold up for long. In less than a year, the city permitted businesses posing as hotels along Fremont Street — the city’s main business district — to sell liquor. This change forced the saloon owners in Block 16 to expand their vice services. At the top of the list was prostitution.

In late May of 1925, reports started circulating of “trouble” in the underworld regarding a possible “shake up” for control. On the night of July 21, 1925, Ferguson made a very public strong-arm move on James. The outbreak of violence at the Arizona Club made the front pages of both Las Vegas newspapers.

“Fires of a feud which have been smoldering for some time past burst forth into lurid flames in the red light district,” the Clark County Review reported. The Las Vegas Age reported that “what is described (as) a wild night” took place “when the clan of one James Ferguson” who appears to “have ambitions to be King of the Tenderloin” stormed the club.

Both papers immediately saw the significance of Ferguson staging a violent brawl inside James’ bar and casino. Following the carnage, James swore out “complaints against Ferguson,” which, the Review stated, “rather speaks for itself to those in the know. The incident bears with it more than usual [significance], since the assaults took place principally in the rooms of the Arizona Club.”

Police arrested Ferguson, and he was charged, the Las Vegas Age reported, with “assault with a deadly weapon with intent to commit bodily injury.” Also among those arrested were three women described by the Age as “denizens of the district.”

Ferguson had enough resources to hire the best lawyer in town, Artemus W. Ham, to defend him, but the court nonetheless convicted him. A judge sentenced him to four months in the county jail.

With his wife and gangster cohorts keeping his plan to dominate Block 16 moving on the outside, Ferguson had successfully pushed his main rival aside. James still owned the Arizona Club, but Ferguson now ran the saloon.

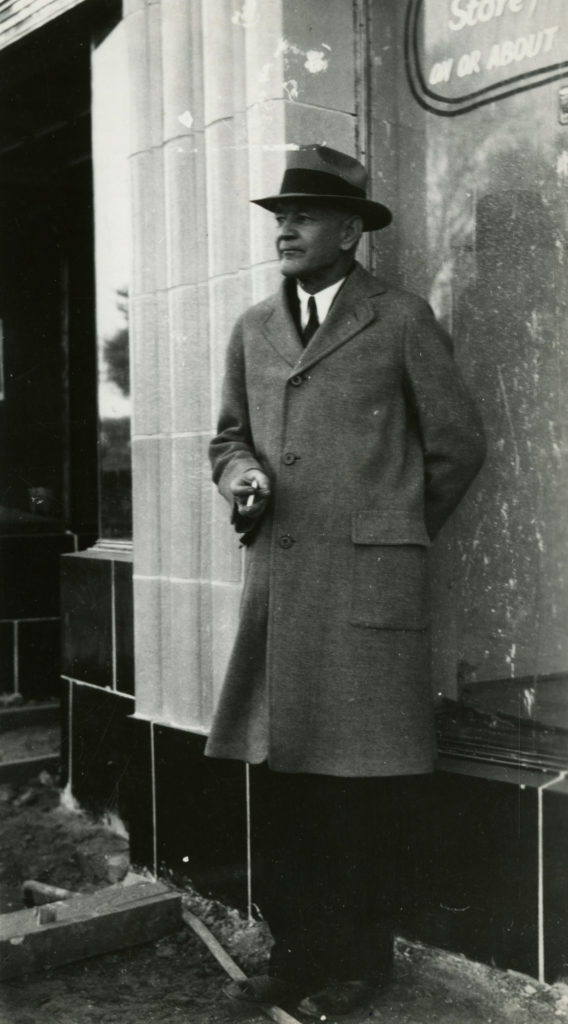

Another development that helped solidify Ferguson’s power base was the appointment of a new city marshal. At its December meeting, the City Commission appointed Robert Earnest “Spud” Lake to serve as city marshal. The job was better known by its unofficial title: chief of police.

Lake was part of a pioneer family that came to Las Vegas in 1904. Over the years, he had served in various local law enforcement positions.

When Ferguson got out of jail in early 1926, he assumed a less public posture, but quietly set up an operation to manufacture and distribute illegal liquor in Las Vegas. Working with Mayor Hesse and Police Chief Lake, Ferguson devised a system of monthly fees and fines. The agreement allowed his bootleggers, both wholesalers and retailers, to operate freely in the city and environs while paying city officials fees to keep the liquor flowing.

Ferguson’s deal with the city brass had both official and unofficial rules. Both sides agreed that Ferguson’s operation would pay a regular, but small fine to the city. The city’s fine would be less than a federal fine. In return, the city would not close down any of Ferguson’s stills, liquor wholesalers or retail outlets. The city also called for Ferguson’s vice businesses in Block 16 to avoid causing problems for the public at large.

Ferguson had a separate plan. He would charge the bootleggers a monthly fee for “protection” in exchange for limited arrests and fines. In some cases, this “protection fee” came with the requirement that the bootleggers buy their whiskey direct from Ferguson’s stills before selling it to saloons and individuals. Ferguson also spread the word that bootleggers who failed to pay him for protection would be arrested and fined more often.

For the rest of 1926 and 1927, Ferguson tightened his control over Las Vegas bootlegging and prostitution rackets, and he cemented his relationships with local law enforcement and city government. At the same time, he expanded his gang’s activity elsewhere in Nevada, as well as parts of California and Utah. Ferguson bragged to federal undercover agents about supplying Southern California mobsters with bootlegged whiskey.

Mayor Fred Hesse ran for re-election in 1928. Based on a recent change to the city charter, if he won, he would be the first Las Vegas mayor to serve a four-year term instead of two years.

In his re-election campaign, Hesse claimed that through his administration’s “most careful management,” most of the “undesirables” in Las Vegas had been “arrested, punished and have departed the city.” The mayor added that the town was “practically free of undesirables.”

Hesse was re-elected. Voters also selected as a city commissioner a newcomer, 30-year-old local businessman Roy Neagle. It was Neagle’s first try at public office. At the first meeting of the City Commission following the 1928 election, Hesse appointed Neagle to oversee the police department.

At the same meeting, Lake kept his job as chief of police, and Joe May as night police officer. The mayor and police chief brought Neagle into the loop on the controls over Ferguson’s bootlegging operation and the city’s vice district.

Robert Stoldal, a longtime television news executive in Las Vegas, is a Las Vegas historian and member of The Mob Museum’s Board of Directors.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org