The bosses of the Mafia Commission were indicted 40 years ago

The case, led by U.S. Attorney Rudy Giuliani, targeted each of New York’s Five Families

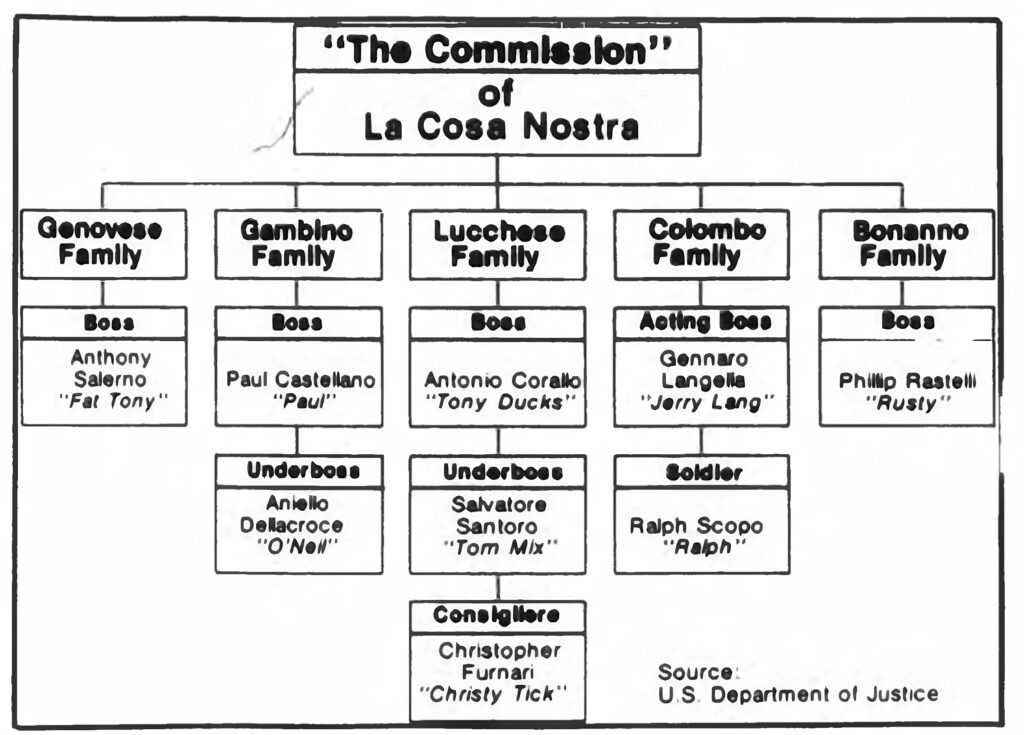

New York, like other major cities across the United States, faced waves of crime during the 1970s and ’80s. What distinguished the Big Apple, however, was the pervasive influence of organized crime, controlling everything from construction to narcotics. The city was the epicenter of America’s most powerful Mafia families, ruled by a board of directors known as the Commission.

Numerous investigations into the Mob’s activities were already in progress by the early 1980s, including the Pizza Connection case, which aimed to stop the Mob’s collaboration with the Sicilian Mafia to traffic heroin. In 1983 a new player emerged on the side of law and order, Rudy Giuliani, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, who soon became the Mob’s archnemesis.

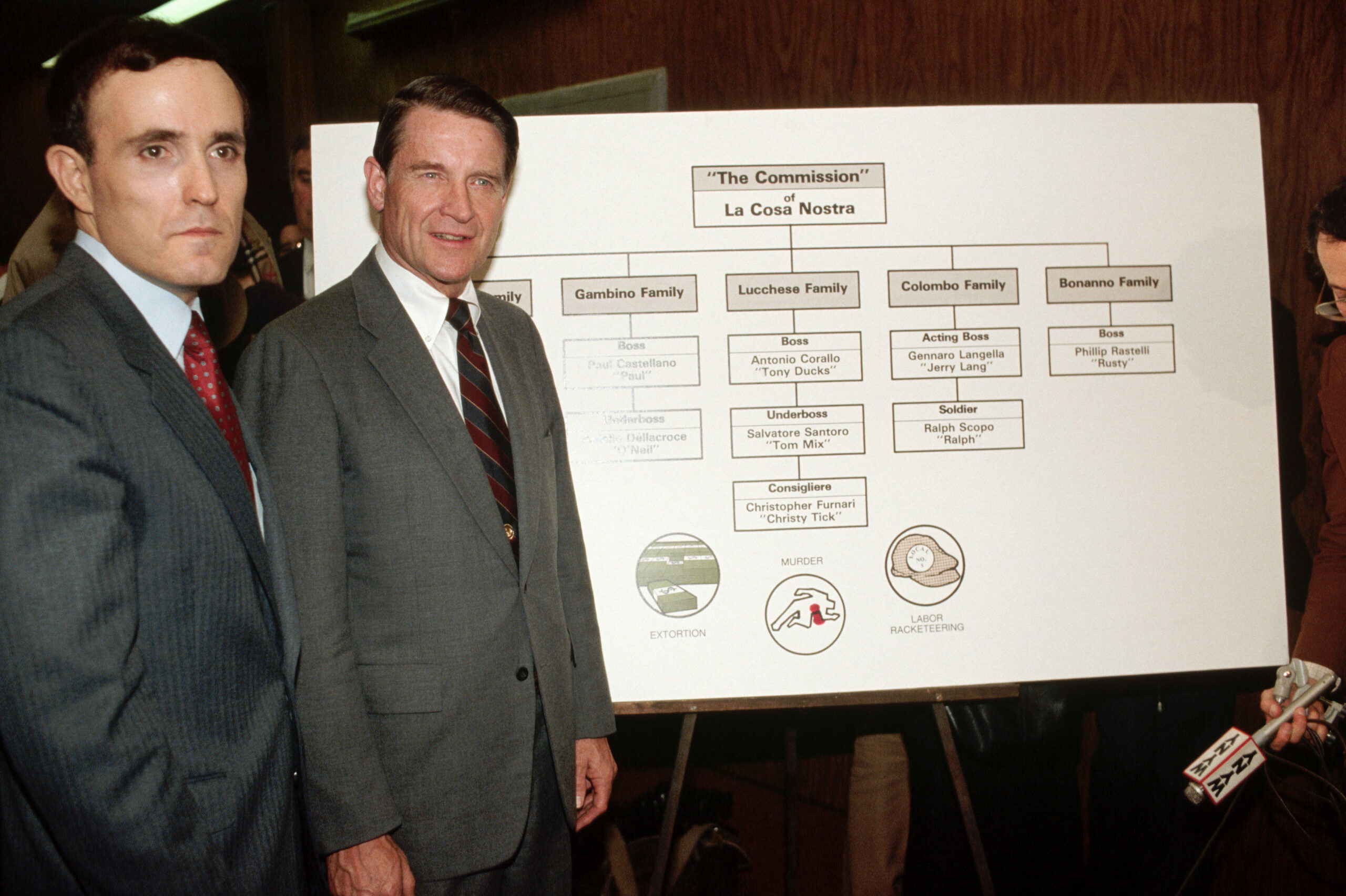

The government’s bold new initiative made waves in February 1985 with the announcement of indictments against nearly all the New York Mafia’s leading figures and some of their associates. This aggressive crackdown on organized crime created a significant ripple effect throughout the criminal underworld and propelled Giuliani into the national spotlight. However, the results of these efforts did not unfold as expected.

Casting the RICO net

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, commonly known as RICO, gave law enforcement a tool to not only catch the little fish but the sharks calling the shots too. However, some officials thought the law was unclear, and critics called it unfair. For a while after its inception in 1970, prosecutors were reluctant to use RICO, and when they did, it wasn’t to its full potential.

“We had RICO for almost 10 years before we knew what to do with it,” FBI Director William Webster said in February 1985.

RICO mandates that the government demonstrate a defendant’s involvement in the operations of a criminal enterprise through “a pattern of racketeering activity.” This pattern is the commission of at least two acts of racketeering in a 10-year timeframe. A racketeering act, often referred to as a “RICO predicate,” encompasses a range of serious federal and state felonies. Consequently, a defendant in a RICO trial may face charges related to various alleged crimes at different times and locations.

The FBI had been surveilling the Mob since 1980 as part of “Operation GENUS.” The investigation brought together federal, state and local agencies, including FBI agents, New York City Police detectives, assistant U.S. attorneys, and attorneys and investigators from the New York State Organized Crime Task Force. Among their most fruitful methods were wiretaps and bugs. Lucchese family boss Tony “Ducks” Corallo and Gambino boss Paul Castellano were both caught in their net. Hidden listening devices recorded damning conversations in Corallo’s car and Castellano’s house.

Once Giuliani stepped into the position of U.S. attorney, his office took the lead in formally going after the five-headed beast.

“It is a great day for law enforcement,” Giuliani said during a press conference. “Probably the worst day for the Mafia.”

The government’s case

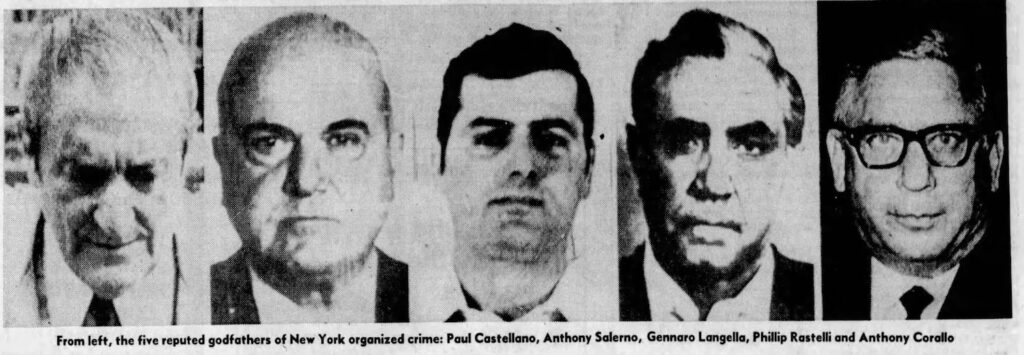

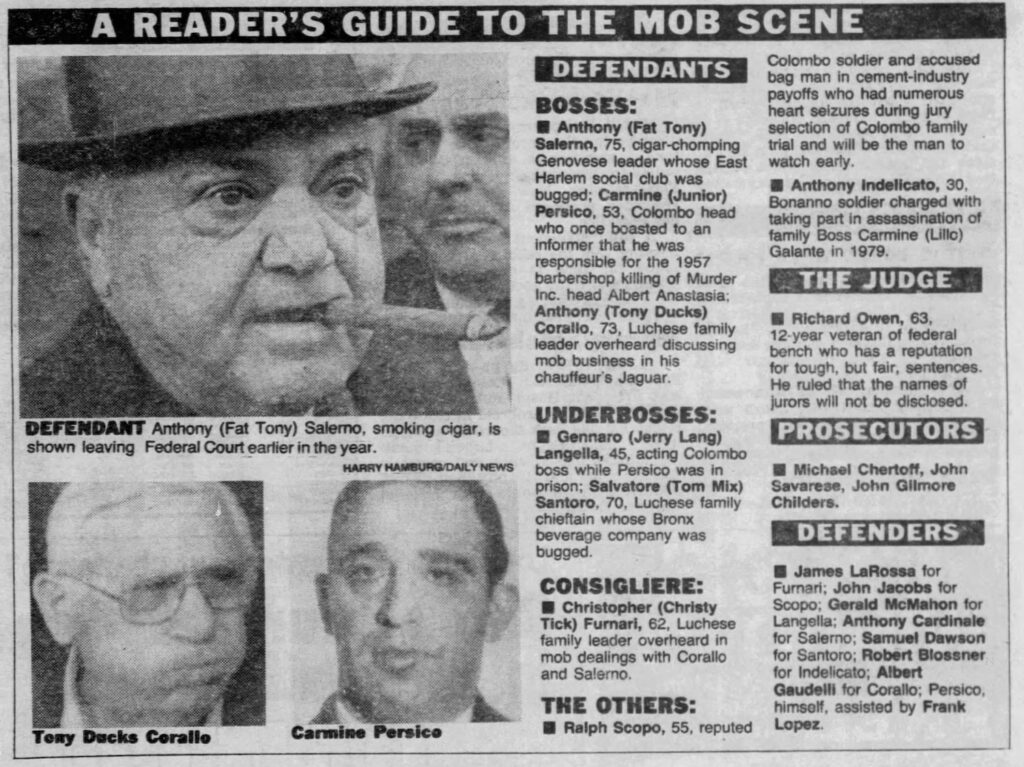

The initial 15-count indictment was announced on February 26, 1985, following an extensive five-year investigation. This effort involved cleverly hidden listening devices, 171 court-approved wiretaps and the dedication of more than 200 federal agents. Some of the defendants had already been arrested days before Giuliani’s press conference, including Castellano and Genovese family acting boss Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno. Both put up a $2 million bail.

In the 1994 book Busting the Mob: United States v. La Cosa Nostra, James B. Jacobs summarizes the government’s argument:

“United States v. Salerno aimed to fell all of New York City’s Cosa Nostra leaders with a single stroke. The indictment charged the bosses of New York City’s Cosa Nostra crime families and several of their subordinates with constituting and operating a ‘commission’ that served as a board of directors and supreme court for the Mob. … In a real sense, the case was about whether it is a crime, meriting life imprisonment, to be a Cosa Nostra boss.”

The indictments targeted the Mob’s role in controlling the lucrative concrete industry and those who received the prized contracts. This group of Mob-associated companies became known as the “Concrete Club.” The indictment also pointed to the Commission’s role in approving murders.

The crux of the government’s case rested on classifying the Commission as a criminal enterprise. Every defendant in the case was a member of the Commission, who, as Jacobs wrote, had been linked to “two or more racketeering acts in furtherance of the Commission’s goals.”

Trial and error

The case went through a few changes before going to trial. Some defendants were added, some were severed and a few died before opening statements began. Additionally, there were some overlapping trials, including Castellano’s indictment a year earlier involving a car theft ring run by notorious Gambino hitman Roy DeMeo.

When the trial commenced in September 1986, the number of indictments had increased to 25, encompassing charges such as extortion, labor racketeering, drug trafficking, illegal gambling and murder. Specifically, three murders were highlighted in the indictment:

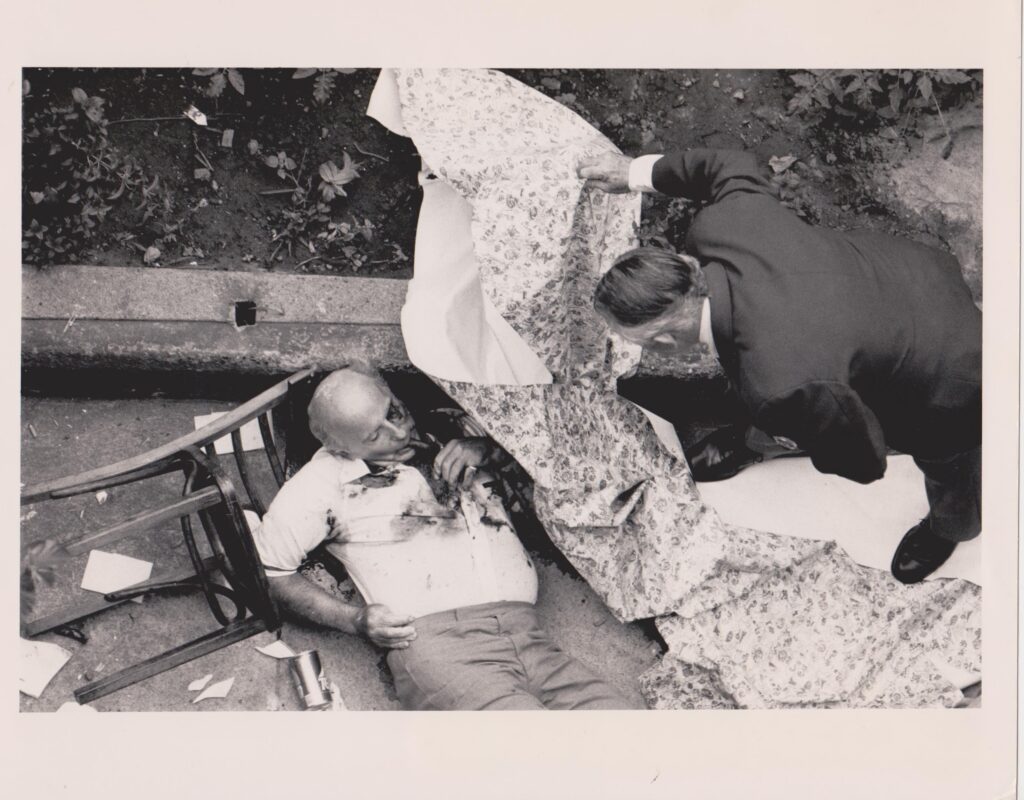

- The murder of Bonanno family boss Carmine Galante in 1979, charged to Gambino underboss Aniello “Niel” Dellacroce and Philip “Rusty” Rastelli. Prosecutors later charged Bonanno capo Anthony “Bruno” Indelicato, who was one of the gunmen, too.

- The murder of Leonard Coppola, a drug dealer killed along with Galante, charged to Dellacroce and Rastelli.

- The murder of Bonanno capo Alphonse “Sonny Red” Indelicato in 1981, charged to Castellano, Corallo and Rastelli.

By the end of 1985, two of the original defendants were dead in short succession. Dellacroce died after a battle with cancer on December 2, 1985. Castellano was gunned down in Manhattan on December 16, 1985. Rastelli had been severed from the case to face unrelated charges while prosecutors added Colombo family head Carmine Persico, who chose to represent himself. Noticeably missing was Genovese boss Vincent “Chin” Gigante, who had been feigning insanity for years, commonly seen wandering the sidewalk in his pajamas and mumbling incoherently.

The Mob’s ill-fated contingency plan, according to the Chicago Sun-Times, was to snuff out informants using outsourced enforcers. The report stated that New York bosses sought assassins from Chicago because their own ranks had been compromised. Their hitmen were also too recognizable to law enforcement. The deal allegedly included giving the Chicago Mob a bigger piece of the national underworld pie, such as more control over Las Vegas gambling.

The verdicts

Officials prosecuting the case, Giuliani in particular, had said early on that this trial wasn’t a be all-end all in taking down the Mob, but that it would open the door for more prosecutions nationwide. The case was the first step in chipping away at the Mob’s power in New York.

The jury delivered guilty verdicts to eight of the defendants on November 19, 1986. Seven received 100-year sentences for racketeering, plus more than $240,000 in fines. Indelicato received 40 years for the murder of Carmine Galante plus a $50,000 fine.

There would be appeals in the coming years, but the defendants remained locked up. Six died in prison, including Salerno, Corallo and Persico. Indelicato and former Lucchese consigliere Christopher “Christie Tick” Furnari were eventually paroled in 1998 and 2014, respectively.

Christian Cipollini is an organized crime historian and the award-winning author and creator of the comic book series LUCKY, based on the true story of Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org