The Black Sox Scandal 100 years later

Gamblers gave baseball a black eye by corrupting the 1919 World Series

It was unseasonably hot at Cincinnati’s Redland Field for the debut game of the 1919 World Series. For the first time in memory, baseball fans attended the Fall Classic in their shirtsleeves. The October 1 series opener, the first since 1918’s was suspended because of World War I, had few of the customary formalities, aside from the famed John Phillip Souza directing a band playing “The Stars and Stripes Forever.”

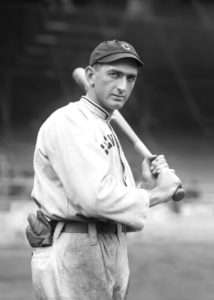

The series pitted the National League’s Cincinnati Reds against the American League’s Chicago White Sox, the winner of the 1917 series. Since the core of the Sox’s team remained, including batting champ “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and ace pitcher Eddie Cicotte, and this was the Reds’ first-ever series, most journalists and gamblers favored Chicago to win again.

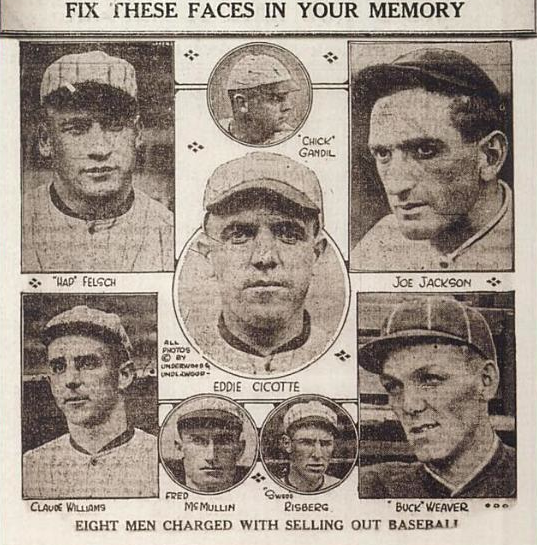

Few outside eight of the Sox’s 24 players knew that illicit gamblers had set up a scheme to pay the players $100,000 to play poorly and “throw” games in the Series so that gamblers could win big wagers on the underdog Reds.

American newspapers, accustomed to covering the World Series with smitten fascination, later would label it the “Black Sox Scandal.” For a game revered by Americans for 50 years since it began, the disgrace stunned the nation. Baseball at the time boasted of having 20 million fans.

The historian Daniel A. Nathan wrote that just months before the 1919 Series, a philosopher, Morris Cohen, proclaimed in a magazine article that American baseball is “a religion, and the only one that is not sectarian but national.” Nathan cited historian Steven A. Riess’ observation that America by the 1920s viewed baseball “as an edifying institution which taught traditional nineteenth-century frontier qualities such as courage, honesty, individualism, patience, and temperance, as well as certain contemporary values, like teamwork.”

Even though gambling was so common that newspapers routinely published betting odds on Major League Baseball contests, the public, and the press, in 1919, perhaps naively, did not suspect players would do anything other than their best on the field despite the heavy wagering.

In 1920 and 1921, the “Black Sox” story regularly hit the front pages of the nation’s newspapers, the mass communication source of the time. During the criminal trial, with seven Sox players and two alleged gamblers as defendants, the New York gambler and organized crime figure Arnold “Big Bankroll” Rothstein was mentioned frequently and became a household name as the supposed mastermind of the “fix.”

Though Rothstein was never charged in the conspiracy, his right-hand man, Abe Attell, was in the thick of it, leaving the implication that the Big Bankroll was involved, if not behind the whole thing.

Game 1

The first allegedly corrupted Reds-Sox game started in Cincinnati at 2 p.m., with the home plate umpire’s wave to the Reds’ dugout to take the field. The Sox’s leadoff batter, John “Shano” Collins, walked to the batter’s box. On the mound was Reds starter Walter Reuther. Collins singled but was out on a force play. The Sox did not score.

In the bottom of the first, the Sox’s star hurler Cicotte threw a strike, then his second pitch went wild and hit batter Maurice Rath in the back. On a hit-and-run, Jake Daubert punched a single, and Rath made it to third. Cicotte threw two other wild pitches, almost hitting the batter, who then hit a sacrifice fly to Jackson, with Rath scoring the first run. Cicotte gave up another walk but the inning ended with a ground out.

In the Sox’s second, Jackson reached on an error and scored after a sacrifice and a bloop single, tying the score. In the Reds’ half, Cicotte threw three balls in a row to one hitter but did not give up a run.

The fourth inning, dubbed “Cicotte’s Waterloo” by the New York Herald, opened with a long fly out caught by centerfielder Oscar “Happy” Felsch. Cicotte threw wildly again, then gave up a single to rookie Pat Duncan. Cicotte stopped a hard grounder, threw to second to force Duncan, but shortstop Charles “Swede” Risberg’s unhurried throw was too late to first basemen Arnold “Chick” Gandil for the double play. A batter reached after a soft fly over shortstop. With two men on, a single scored a run. Then up to bat was Reds pitcher Reuther. In one of his three hits that day, he cracked a ground-rule triple into the crowd in left center, scoring two.

Cicotte then gave up a single to Rath, scoring Reuther. Rath scored on a deep hit by Jake Daubert. Reds manager Kid Gleason waved in Roy Wilkinson to relieve Cicotte, who left the mound with his head cast down. He’d given up six runs and seven hits in 3 and 2/3rd innings.

“At the very beginning,” remarked a Herald sportswriter the next day, “Cicotte demonstrated that he was not in form. He could not control his spitball, which he appeared to use more often than ever.”

In later innings, the Sox looked to put up a fight. Risberg made a great grab behind second base to nail a runner in the fifth and assisted in a double play in the sixth. But in the seventh, the Reds scored on a triple and a scratch hit past Risberg. Sox third baseman George “Buck” Weaver fielded a bunt but threw wildly to first and the runner collided with first baseman Gandil, who dropped the ball. The Reds scored again on an infield grounder to shortstop Risberg, who threw to second for the force. Risberg then took part in another double play. The score was Reds 8, Sox 1.

The Reds scored again in the eighth inning. White Sox slugger Joe Jackson did little at the plate, flying out in the ninth and going 0-for-4 with one run scored. The final score for was 9-1 Reds.

Before the game, the published betting odds, based on prevailing gambler wisdom known as the “dope,” were for the Sox to win the series. Some odds favored the Sox, from 5 to 4 to 3 to 1. After the Reds’ first game win, the betting line on the Sox shifted to even money (dollar for dollar).

The Reds also won the second game, 4-2. But the Sox came back in the third game, blanking the Reds 3-0. Cincy shut out the Sox 2-0 in the fourth, and 5-0 in the fifth. The Sox raised concerns by taking the next two, 5-4 in 10 innings and 4-1 in the seventh game. However, the Reds prevailed in the deciding contest, 10-5 – in which Jackson hit the series’ only home run — winning the best of nine championship five games to three.

Suspicions grow

For the Series, the Sox’s so-called ace Cicotte yielded 19 hits and 9 runs (7 earned) in 21 2/3rd innings, with one win (game 6) and two losses (games 1 and 4). The Sox’s other good pitcher, Claude Williams, suffered three losses, giving up 12 hits and 12 runs (11 earned) in 16 1/3rd innings.

Jackson led both teams with 12 hits and a .375 batting average, and teammate Weaver had 11 hits and a .324 average. Both had perfect fielding percentages. The two teams committed 12 errors. The Reds’ team batting average stood at .255 and the Sox’s at .224. Runs scored was not close – the Reds had 35 vs. 20 for the Sox.

At first, sportswriters covered the Sox’s defeat normally, but then suspicions grew as to why the Reds won when “the dope” clearly favored the Sox. One reporter stood out — syndicated columnist Hugh Fullerton, a well-known dopester whose predictions on pro and college teams were read closely by both fans and gamblers. His take before the Series was that the Sox would win in seven games, and the failure of the Sox affected his reputation. Maybe with some bitterness, on October 10, after the Sox’s loss in Game 7, Fullerton ran a column calling the team into question, triggering a national conversation.

“Today’s game in all probability is the last that ever will be played in any world series,” he wrote. “… Today’s game also means the disruption of the White Sox as a ball club. There are seven men in the team who will not be there when the gong sounds next spring, and some of them will not be in either major league.”

Fullerton then wrote in the New York Evening World on December 17, 1919, about the end of a two-month secret investigation by detectives hired by Sox owner Charles Comiskey. The investigators, Fullerton reported, had “been unable to find evidence that there was dishonesty among the players of his team during the recent World Series.”

Comiskey assigned the detectives after Game 2, when an unidentified gambler “went to him and told him the stories being circulated through the underworld of sport,” Fullerton wrote. Comiskey also offered $10,000 for anyone to provide “legal proof that his players were not trying.” Since no one took the owner up on the offer, Comiskey concluded the “fix” story was not true. Still, Fullerton remained concerned about gambling’s potential effect on baseball.

“It is not the seven players who are indicted by common gossip that are on trial,” Fullerton continued. “It is the good name of baseball and the honesty of hundreds of players who are not mentioned.”

Fullerton accused baseball owners of trying to drop inquiries into the 1919 Series, which, if true, “would serve to convince thousands of fans that there is something in the stories.” He called for an investigation headed by Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a respected federal judge, among “the best cross examiners of witnesses in the country” and “one of the most loyal followers and lovers of baseball.” Fullerton asked that Landis question a number of witnesses, including gamblers Arnold Rothstein, Mont Tennes, Karl Zork, Lou and Ben Levi, Abe Attell, Joe Pesch and former White Sox and Reds pitcher Bill Burns.

The columnist’s writing sparked some discussion in newspapers about the influence of gamblers on baseball. But what really got the ball rolling on the Black Sox Scandal was an unrelated case months later, involving Chicago’s National League team the Cubs and the league’s Philadelphia team, the Nationals.

Allegations of gamblers “fixing” a routine regular season game played by the Cubs and Nationals on August 31, 1920, prompted a grand jury investigation in Chicago. The Chicago Tribune reported on September 5 that the Cubs’ office received five telegrams from Detroit on August 31 – before the game — warning of heavy betting on Philadelphia over the Cubs in major U.S. cities. Gambler sources told the newspaper that odds on the game switched from favoring the Cubs to the Phils after “a plot to throw the game” by four members of the Cubs.

The Cubs, minutes before the game started, responded to the reports by starting their ace pitcher, Grover Alexander, in place of Claude Hendrix whose turn it was in the rotation. The Cubs offered Alexander a $500 bonus if he won. The Phils prevailed anyway, 3-0, giving gamblers who bet on whisperings of a “fix” a big payday. Still, the Tribune reported, “no one who saw [the game] could point out any incident that would prove it was fixed.”

Detectives hired by the Cubs could not confirm that the people whose names appeared on the August 31 telegrams lived in Detroit, and some contained fake addresses. Speculation arose that Detroit gamblers sent the messages to encourage the Cubs to pitch Alexander, and win money from those betting on the Phils. The Tribune also mentioned “a rumor that at present time three members of the White Sox are under suspicion [of ties to gamblers], yet are playing the game regularly.” In one case in New York, a gambler won $70,000 on a Sox-Reds World Series game, according to the paper.

Cubs President Bill Veeck said he would “spare no expense to investigate the charges” about the August 31 game. The Associated Press reported that Veeck’s detectives learned that gamblers from Detroit, Boston, Cincinnati and Chicago laid $50,000 on the Phils for the game, throwing the odds from 2 to 1 for the Cubs to 6 to 5 favoring the Phils.

When the grand jury started taking testimony that month about the August 31 game, investigators called forward Sox players, including Cicotte and Jackson, for questioning to address related reports about the actions of gamblers in the World Series. That’s when the lid blew off the Black Sox Scandal.

Public confessions

On September 28, Cicotte, 38 years old and an 18-year baseball veteran, broke down and cried on the stand as he admitted he took a $10,000 payoff from gamblers. He said that Sox player “Chick” Gandil served as the go-between handling money from the gamblers and received $20,000.

“This is terrible for my family,” Cicotte said. “My poor kids – oh, why did I do it? I’ve lived a terrible year in the last 12 months.”

He admitted that the whole plan was his idea. “I refused to pitch a ball until I got the money. It [the $10,000 in cash] was placed under my pillow in the hotel the night before the first game of the Series. Every one [of the players] was paid individually, and the same scheme was used to deliver it.”

Cicotte admitted to deliberately hitting the leadoff batter in Game 1 and that in Game 4, he purposefully intercepted a throw from Jackson in the outfield that would have caught a Reds player, and made a wild throw to first, both resulting in two runs for the Reds, who won 2-0. He said he and fellow pitcher Williams also ignored pitch signals given by catcher Ray Schalk, who was not in on the scam.

Jackson, on the stand, put his face in his hands and confirmed Cicotte’s story, mentioning that he joined in after talking to players Gandil, Risberg and Fred McMullen, who each worked with the gamblers. He admitted accepting $20,000 for making some fielding errors and not getting hits in key moments. He found $5,000 in cash on his hotel bed before the Series and believed he’d get the other $15,000 once the gamblers won their bets, but he never did.

Following Jackson’s two hours of testimony, reporters overheard him telling a friend: “I got a big load off my chest. I’m feeling better.”

The grand jury immediately indicted eight Sox players. Sox owner Comiskey just as quickly ordered them suspended from the team.

Williams testified the next day, confessing that Gandil gave him $10,000 in cash, half of which Williams in turn gave to Jackson. He said that gamblers named “Brown” and “Sullivan” were his go-betweens for the currency. The eight Sox players, he claimed, went to Cicotte’s hotel room to meet with Brown and Sullivan and made separate deals, after declining to accept only $5,000 each. Williams pitched wildly in his losses in Games 2 and 5 and his walks in Game 8 resulted in winning runs for the Reds.

The most revealing witness was Billy Maharg, a former Cubs catcher whose real name was “Graham,” or Maharg spelled backwards. Maharg said that Cicotte himself thought up the whole plan, by contacting gamblers and requesting Sox players be paid $100,000 to throw the Series.

He said that in a New York hotel, he met with the gambler Burns and that Cicotte showed up and spoke to Burns.

According to Maharg, “I heard enough to know that he said that a group of prominent players of the White Sox would be willing to throw the World Series if a syndicate of gamblers would give them $100,000 on the morning of the first game. When Cicotte left, Burns turned to me and repeated Cicotte’s conversation, part of which I had heard. Burns said, ‘Do you know any gamblers who would be interested in this proposition?’ I said I would go to Philadelphia and see what I could do. Burns said he would have to go to Montreal to close an oil deal and that he would wire me about the progress of the deal.”

Rothstein involved?

Maharg said he went to Philadelphia and gamblers there told him “it was too big a proposition for them to handle,” and they recommended he talk to “Arnold Rothstein, a well-known and wealthy New York gambler.” Maharg took the advice, met with Rothstein in New York and put it to him, but Rothstein “declined to get into it. He said he did not think that such a frame-up could be possible.”

However, Maharg said when he returned to Philadelphia, Burns sent him a telegram that read: “Arnold R has gone through with everything. Got eight in. Leaving for Cincinnati at 4:30.”

Burns, Maharg said, met with fellow gambler Attell, an ex-featherweight prizefighter, in New York after their meeting with Rothstein, got Rothstein to agree to the deal as well as Cicotte and the other seven Sox players. Maharg said someone informed him that Attell worked with Rothstein and was in a hotel room in Cincinnati with 25 New York gamblers to work on the Series scheme.

Maharg said he was apprehensive on the morning of the first game, when he visited Attell with Burns. “We asked for the $100,000 to turn over to the White Sox players to carry out our part of the deal. Attell refused to turn over the $100,000, saying that they needed the money to make bets. He made a counter proposal of handing the players $20,000 at the end of each losing game. Burns went to the Sox players and they seemed satisfied with the new arrangement.

He and Burns bet Cincinnati in the first game and won. They went to see Attell at the hotel and “I never saw so much money in my life. Stacks of bills were being counted on dressers and tables.” But Attell stalled again on another payment, saying he needed it for betting. Maharg asked Attell if Rothstein was really part of the deal, and Attell gave him a telegram signed “A.R.” that they later learned was a fake.

“As a matter of fact, Rothstein was never involved,” he said. “Attell was lying.”

With the second game over, Attell made excuses, but gave Burns $10,000 for the players. Burns believed the players were “restless” and thought they would not see the rest of the money. The Sox players said they did not expect to win Game 3, with rookie pitcher Dickey Kerr on the mound.

Maharg and Burns put all their winnings on Cincinnati, but “the Sox got even with us by winning this game. Burns and I lost every cent we had in our clothes. The whole upshot of the matter was that Attell and his gang cleaned up a fortune and the Sox players were double-crossed …”

Before the criminal conspiracy trial, original copies of the grand jury confessions and immunity waivers signed by Cicotte, Jackson and Williams mysteriously vanished from the Illinois State’s Attorney’s office. The news incited rumors that gamblers had paid to have the documents stolen to help the players. Cicotte, Jackson and Williams each recanted their confessions, and their lawyers sought to suppress the admissions from the trial.

Black Sox on trial

When the trial was ready to start in Chicago on March 17, 1921, state prosecutors claimed some witnesses had been corrupted and asked for a postponement. When the judge refused, the state’s attorney dropped charges against the now ex-players, and the judge took the other defendants off the court calendar.

Then on March 27, a second, this time secret grand jury again indicted the eight former Sox players, and 10 other defendants for a total of 18, on multiple counts of conspiracy. The ex-players charged were Cicotte, Jackson, Williams, Gandil, Felsch, Weaver, Risberg and McMullin. Others charged included gamblers Attell, Rachel Brown, Benjamin Franklin, John “Sport” Sullivan, David Zelcer, Carl Zork, Lou and Ben Levi, plus former ballplayers Burns and Hal Chase.

By the time the trial rolled around in 1921, prosecutors dropped charges against the Levi brothers for lack of evidence; Attell avoided extradition – and thus prosecution — from New York to Chicago; authorities could not apprehend Chase, McMullen, Brown and Sullivan, and Franklin was deemed too ill to make it.

Defense lawyers tried unsuccessfully to keep the jury from hearing of the confessions made by Cicotte, Jackson and Williams before the grand jury. Witnesses Burns and Maharg repeated in court what they had said to the grand jury about the scheme by them and the players to throw the games.

State prosecutors pressed for five-year prison sentences and $2,000 fines for each defendant. Assistant State’s Attorney Edward Prindiville, in his final argument to the jury, blasted the former Sox players as “traitors who for $100,000 of dirty money sold their souls, betrayed their comrades and the public and conspired to make the only truly American pleasure and sports – baseball – a confidence game.”

But Judge Hugo Friend raised the bar up high for prosecutors to obtain convictions. He told the jury that instead of merely proving the former Sox players and other defendants conspired to lose baseball games, the state had to show that they had defrauded the public in doing so.

On August 2, 1921, after less than three hours of deliberation, the jury found all nine defendants – seven ex-players and gamblers Zork and Zelcer — not guilty of the 10 conspiracy charges. The verdict was met with cheers, whistles and hats thrown into the air in the crowded courtroom. Some onlookers yelled “hurrah for the clean Sox!”

Burns got off for his cooperation. Prosecutors later dropped charges against Attell, Chase, McMullen, Brown, Sullivan and Franklin.

Questioned by reporters after the court adjourned, jurors complained of weaknesses in the state’s case against the defendants. One juror asserted that prosecutors relied too much on the testimony of Burns, who “did not make a favorable impression with any of us.”

Banned for life

The new commissioner of baseball, Judge Landis, appointed to clean up the sport amid the scandal, declared sternly in a statement a day afterward that all players charged in the Black Sox Scandal were banned for life from the major leagues.

“Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a game, no player that throws a ball game, no player that entertains proposals or promises to throw a game, no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it will ever play professional baseball.”

Williams expressed his desire to play in semi-pro baseball leagues. Weaver and Risberg hoped to return to the majors but never did, nor did any of the former Sox players.

Rothstein, never legally implicated in the Sox affair, remained the nation’s richest gambler and his fortunes grew with his reputation as an influential organized crime figure in the 1920s. In 1928, a gambler who claimed Rothstein owed him more than $200,000 shot and mortally wounded him in New York.

Attell, a former world feather featherweight champion and Rothstein’s bagman, reportedly fled to Canada during the conspiracy trial and then faded into obscurity. Ring magazine placed him into its Boxing Hall of Fame in 1955. He died in 1970.

Jackson, who opened a store in Chicago, proclaimed after the trial that he was done with baseball, although he would play semi-pro ball for some time thereafter. He was the greatest loss to the major leagues. His career batting average over 13 seasons, .356, remains the third highest in baseball history, bested only by Ty Cobb’s .366 and Rogers Hornby’s .358. He batted .408 in his first full season in 1911. His 1919 regular season average was .351. He hit .382 with a career-high 121 runs batted in during his last year with the Sox in 1920 before his suspension.

Of the famous story in the Chicago Daily News by Charley Owens that a kid outside the Chicago courtroom in 1920 told him, “Say it ain’t so, Joe,” Jackson many years later told a journalist, “There wasn’t a bit of truth in it … Charley Owens just made up a good story and wrote it.”

“Shoeless” Joe Jackson died at age 64 in 1951. He played for the Cleveland Indians for six seasons before joining the Sox, and is in the Indians’ Hall of Fame.

As for baseball fans, they soon moved on from the drama, having something new to follow in pro baseball – home run king Babe Ruth. The season when the Black Sox Scandal broke in 1920, Ruth hit a record 54 home runs. He hit 59 more in 1921.

Of Jackson, Ruth is quoted as saying: “I copied Jackson’s style because I thought he was the greatest hitter I had ever seen, the greatest natural hitter I ever saw. He’s the guy who made me a hitter.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org