Seventy-five years later, debate over Bugsy Siegel murder still rages

Numerous theories advanced about what happened on June 20, 1947, and why

As Americans opened their newspapers on June 21, 1947, they saw large headlines about the murder of Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, who, according to a United Press story, was the “nation’s No. 1 gangster.” As Time magazine noted, “for a managing editor who likes a good, splashy crime story, the murder of Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel in a Beverly Hills mansion had everything.” For several days, “the tabloids of Manhattan, the sensational papers of Los Angeles and, to a lesser degree, papers all over the U.S. played it high, wide & handsome.” Because this crime has never been solved, it still captures our attention. While we know what happened to Siegel, there is much speculation about who killed him and why.

Siegel had arrived in Los Angeles early in the morning of June 20. He had been successful in completing the construction of the Flamingo casino with a fabulous opening on December 26, 1946, and of the hotel, which had opened on March 1. The property had begun to make a profit, but Siegel still faced substantial unpaid construction costs. Those around him in May and early June saw a man worried about how to pay off those debts, a man who needed to take a few days off from the stress.

Siegel had leased a house at 810 North Linden Drive in Beverly Hills for his mistress, Virginia Hill. She had run off to Paris after another of their many spats. Since the lease was about to end, Siegel needed to collect some clothes. He also had scheduled a meeting with publicist Paul Price and his lawyer, Joe Ross, to discuss a promotion campaign for the Flamingo. Most importantly, his daughters, Millicent and Barbara, were going to join him in Los Angeles for a vacation. He had divorced his wife, Esta, the previous August, and this would be the first time since October to see the girls, who were traveling by train from New York.

That evening Siegel went to dinner with his friend Allen Smiley, Hill’s brother Chick and Hill’s secretary Jerry Mason, who was going to marry Chick. Smiley drove everyone back to the home on North Linden Drive, where he and Siegel relaxed on a sofa, as Smiley later explained, “chinning and skimming” newspapers. Mason and Hill went upstairs.

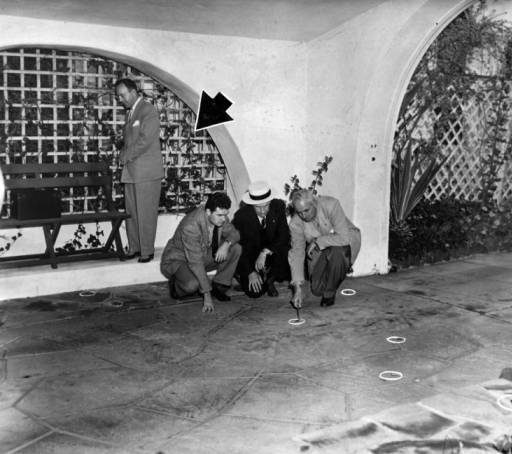

Siegel and Smiley chatted, blissfully unaware that someone was standing outside a window to their right. He rested a .30-caliber military carbine on the trellis just outside the window. The muzzle of the shooter’s gun was less than 14 feet from Siegel. A little before 11 p.m., he fired nine rounds. One hit the bridge of Siegel’s nose and knocked out his left eye, another round hit him in the right cheek, and two hit him in the chest. The other rounds hit the wall behind Siegel.

One of the rounds had gone through Smiley’s jacket, but he was not wounded. He told the police, “I heard the glass shattering, and I ducked. I don’t know how many shots were fired, but when I looked at Siegel, I could see he had taken most of them.” Some neighbors rushed into the street after hearing the shots and saw a car that raced away. Hill called the police, who arrived on the scene within minutes.

In the early days of the investigation, Los Angeles County deputy district attorney Ernest Roll told reporters, “There might have been a hundred different people who wanted him out of the way.” This led journalists to raise all kinds of questions about the motive for killing Siegel. Had he crossed the wrong person in narcotics trafficking, or in the struggle to control the horse race wire service? Had he spent too much of the Mob’s money in completing the Flamingo, or had he skimmed their money? Had someone killed him for his ill treatment of Virginia Hill? Fairly quickly, Roll reluctantly concluded that Siegel’s shooter may “never be identified.” But over the past seven decades, gangster enthusiasts, journalists, historians and biographers have offered a variety of solutions to the crime.

One of the most enduring explanations for the hit on Siegel concerns a summit of Mob leaders that convened in Havana, Cuba. There is disagreement over whether it took place in December 1946 or February 1947, but most authors argue that notable underworld leaders Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Frank Costello and Meyer Lansky were in attendance. Those who support this theory argue that the leaders of the New York Mob decided that Siegel had to be eliminated, either because he had wasted or stolen their money.

Those who subscribe to this theory usually add that the Mob leaders designated Southern California Mafia boss Jack Dragna to carry out the hit. Depending on the author, Dragna ordered one of three men to kill Siegel: mobster Frankie Carbo, mobster Eddie Cannizzaro or World War II veteran Robert McDonald, who, according to author Warren Hull, had a significant gambling debt he owed to the Mob.

In his co-authored 2013 book, Beverly Hills Confidential, Clark Fogg, who for many years was the senior forensic specialist in the Beverly Hills Police Department Lab, argued that there had actually been two shooters. Fogg concluded that “it would have been nearly impossible for just one gunman” to make such precise shots to Siegel’s face because “the mobster’s head would have turned upon impact from the first bullet.” He further believes mobster Joe Adonis hired the “Two Tonys,” Tony Brancato and Tony Trombino, to kill Siegel because he was stealing from the New York Mob.

In July 1947, an FBI informant reported another intriguing claim about the identity of Siegel’s shooter, one that has also endured well into the 21st century. The informant said Meyer Lansky had suggested that Virginia Hill’s brother “may have killed Siegel because of Siegel mistreating Hill.” Siegel had been with Hill frequently for about five years, and, despite their having a passionate affair, they often fought. Bernie Sindler, who worked at the Flamingo in 1946 and 1947, made the same claim in his 2015 memoir, The Bernie Sindler Story.

Gus Russo, who wrote Supermob, a book about lawyer Sidney Korshak, who represented actors, corporate executives and mobsters, offered a variation on that theory. Russo said that Korshak was persuaded that Moe Dalitz, an underworld figure from Cleveland, had authorized the hit on Siegel because of his abuse of Hill, who had, for a time, been Dalitz’s lover. Screenwriter Edward Anhalt, who lived next to Hill for a time at the Chateau Marmont in West Hollywood, agreed. Anhalt described having dinner with Siegel in the spring of 1947 and having their meal interrupted by the maitre d’ handing Siegel an envelope. After reading the message inside, Siegel “really looked worried.” Anhalt contended that a friend told him the letter was from Detroit (Dalitz was also associated with the Detroit Mob) warning Siegel to leave Hill alone.

In 2014, Amy Wallace, in Los Angeles Magazine, published a story that placed Moe Sedway, a longtime associate of Siegel’s, at the center of this murder. She drew upon an unpublished book proposal written by Moe’s widow, Beatrice. In her account, Bee claimed that Siegel planned to have her husband killed when he learned that Sedway was keeping a precise account of the business of the Flamingo and reporting the worsening debt situation to Meyer Lansky. Bee further claimed that Moe learned of Siegel’s plan and responded swiftly, getting Lansky’s approval to have Siegel murdered instead. The shooter, according to Bee, was Mathew “Moose” Pandza, a man with whom she was having an affair.

Wallace wrote that Pandza followed Siegel’s movements on June 20 and drove behind Smiley to the house on North Linden Drive. After shooting Siegel, Pandza jumped into his car and “didn’t stop driving until he pulled into an alley in Santa Monica, where he broke down the rifle. He tossed the barrel into the ocean, the butt on a rooftop.”

Amid these conflicting claims, some things about the Siegel murder are clear. Most notably, it was a well-planned hit. On the evening of the shooting, during the 8:30 show at the Flamingo, eight men left their table in the showroom and moved quickly to the security desk, front door, casino cage and hotel registration desk, obviously to secure the property for what was to come. Immediately after the shooting, Allen Smiley called a man who answered in a telephone booth just outside the Flamingo. The man had become an informant for Las Vegas FBI agent Curtis Lynum. Smiley told the informant that “Siegel had been shot in the face and chest, and he knew he was dead.” Only moments after Smiley’s phone call, Moe Sedway, along with Gus Greenbaum and Morris Rosen, walked into the Flamingo and announced that Siegel was dead, and that they were in control of the property.

Although agent Lynum did not name his “super informant,” he did describe him. Lynum explained that before his arrival in Las Vegas in April 1947, a man came into “the Las Vegas resident agency and said he wanted to ‘help the FBI.’” Local agents had been able to verify the informant’s claims about the “underworld.” Moreover, as was true with Sedway, this informant “had a wife and children living in Los Angeles” while “he kept a mistress in Las Vegas.” He also “was thought to be a legitimate businessman” in town. Lynum explained that the informant’s “first information of importance . . . was keeping me advised of Siegel’s activities.” All of this evidence points to Sedway as the “super informant.” Indeed, FBI reports in both 1948 and 1951 identify Sedway as a “confidential informant” in Las Vegas. Knowing he most certainly was the informant Allen Smiley called after the shooting makes it easier to understand how Sedway, along with Greenbaum and Rosen, were in a position to enter the Flamingo so soon after Siegel died.

There is some circumstantial evidence from 1947 that confirms this conclusion. In August, an FBI agent in Las Vegas reported that someone (name redacted in FBI report) in the local police department told FBI agents that he had concluded that Sedway had “engineered the killing” because Sedway had “acted peculiarly just before Siegel was killed, and that since the killing he has been ‘nervous as a cat.’” In addition, Clinton Anderson, the chief of police in Beverly Hills, told Siegel biographer Dean Jennings, “I was convinced, and still am,” that Sedway “had a hand in the Siegel killing. He knew who did it.”

Moe Sedway did not pull the trigger, but he clearly played a role in the Siegel murder. He had to have been in close communication with the shooter or with someone who knew immediately that there had been a successful hit on Siegel. Otherwise, he would not have known when to march in and take over the Flamingo.

There is more to learn about the Siegel murder in Crime Case #46176 in the Beverly Hills Police Department. Unfortunately, because the Siegel case is an open one, researchers cannot view the file.

Larry Gragg is curators’ teaching professor emeritus of history at Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla, Missouri. He has published 10 books, including Bright Light City: Las Vegas in Popular Culture (2013), Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel: The Gangster, the Flamingo, and the Making of Modern Las Vegas (2015) and Becoming America’s Playground: Las Vegas in the 1950s. His biography of Moe Sedway, titled Escaping Bugsy’s Shadow: Moe Sedway and Bugsy Siegel in Las Vegas, will be published in 2023 by the University of New Mexico Press.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org