Robert F. Kennedy’s crusade against the Mob: Part 2

Between 1957 and 1959, Kennedy and the Rackets Committee collided with Teamsters bosses and Mafia mavericks

Second of three parts

The Senate Rackets Committee made national news as soon as it started its work in early 1957. The bipartisan panel, which the Senate unanimously approved on January 30, 1957, was assigned to investigate labor union racketeering. Vice President Richard Nixon formally appointed its eight men – four Democrats, four Republicans – from a list of senators provided by Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas and Minority Leader William Knowland of California. Senator John McClellan of Arkansas was appointed chairman and Robert Kennedy chief counsel. Among the committee’s members were Senators John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, Barry Goldwater of Arizona and Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin. The committee almost immediately requested information from federal agencies on how they monitored labor unions and started issuing subpoenas to Teamsters Union officials, compelling to them to testify.

That week, syndicated labor news columnist Victor Riesel, blinded in an acid attack in New York ordered by a Mob associate only months earlier, wrote a column observing that “(t)here is no federal law against embezzling welfare and pension funds, not even if you take a million dollars. And they (mobsters) have taken a million – at one clip, too.” He praised committee counsel Robert Kennedy, whom, Riesel wrote. “is not idly curious. This is the most skillfully thought-out campaign against the labor rackets in years.”

Off the bat the committee in February asked Teamsters President Dave Beck to hand over his financial records for review or receive a subpoena for them. Beck ducked those requests while on a long trip to Europe, but told reporters in Vienna that we would comply once he returned to the States. Then in late February, one of the first of many sensational news stories to emerge from the committee broke when the hearings centered on political corruption and labor racketeering in Portland, Oregon. James E. Elkins, the admitted boss of the vice underworld in Portland, agreed to spill what he knew from the inside. Elkins declared that racketeers sent by West Coast Teamsters boss Frank Brewster attempted to extort operators of coin-operated pinball machines in Oregon – which took in about $250,000 a year – by forcing the state’s tavern owners and other locations to use machines with the Teamsters’ union stamp. If they did not comply, the Teamsters sent members to picket outside the businesses and block deliveries of beer until the unstamped machines were removed. Only machines sold by the Acme Amusement Co. – run by a Seattle gambler dispatched to Portland by Brewster – had Teamsters stamps.

Elkins told the committee about a meeting he had in Seattle with Brewster, who demanded he allow a pair of Teamsters men to talk over control of gambling, prostitution and other vice rackets in Portland. Elkins said that Brewster then added: “I make mayors and I break mayors, and I make chiefs of police and I break chiefs of police. I have been in jail and I have been out of jail. There is nothing scares me. … If you embarrass my two boys, you will find yourself wading across Lake Washington with a pair of concrete boots.” Brewster later denied the statements, saying Elkins spun “a fantastic story.” Eventually, Elkins said, Brewster gave up the Oregon pinball racket when a top machine operator, Stanley Terry, provided the Teamsters official with a $10,000 payoff.

Elkins provided the committee with tape recordings he secretly made of conversations with various characters in Portland, including Portland District Attorney William Langley. When Langley came to testify, the committee played one of Elkins’ recordings during which Langley was heard telling Elkins that he wanted $8,500 to permit Elkins’ rackets to continue. In response, Langley pled the Fifth to avoid self-incrimination. When questioned by Robert Kennedy over a $500 check made out to Langley from the Teamsters, the witness stoically pled the Fifth again.

As the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Robert Kennedy in Los Angeles is recognized this week – he was shot on June 5, 1968, and died the following day – one aspect of his complex legacy is less likely to be emphasized: his unprecedented crusade to expose and prosecute the Mob in America. It was a time when the national syndicate held considerable power and influence over business, entertainment, unions, illegal gambling, prostitution, politics, the courts, and all levels of government and law enforcement. Robert Kennedy played a huge role in exposing underworld activities across the country.

Targeting the Teamsters

Only weeks into the Rackets Committee’s existence, Teamsters President Beck, knowing the Senate panel had the union in its sights, directed his well-paid public relations man, a Washington lawyer named Eddie Cheyfitz, to invite Robert Kennedy to dinner with Teamsters Vice President James Hoffa in an attempt to soften things up. But Cheyfitz was a pawn used by Hoffa, who wanted to take over for Beck as union president and lobby RFK into thinking Hoffa would institute reforms against alleged misuse of funds, extortion and other corrupt practices by the Teamsters’ leadership.

Cheyfitz induced both men to dine at his place in Chevy Chase, Maryland, on February 19, 1957. Kennedy, however, did not reveal he’d heard that Hoffa had covertly tried to pay a New York lawyer, John Cye Cheasty, $2,000 a month up to $18,000 to get to a job with the committee in order to serve as Hoffa’s spy on the goings-on. The evening dinner was tense, though Hoffa impressed RFK with frank answers to his direct questions about possible labor corruption. Kennedy didn’t let on that he knew about Hoffa’s association with New York mobster Johnny Dio, criminally charged in the assault that permanently blinded Victor Riesel. After Kennedy left, Hoffa told Cheyfitz, “He’s a damned spoiled jerk.”

The Rackets Committee prepared to hit Beck and Hoffa with the findings of its investigators into misuse of union money. But first, Kennedy and the FBI set about springing a trap for Hoffa. Earlier, RFK brought in Cheasty to tell McClellan his story about Hoffa’s alleged attempt to bribe him. The chairman contacted FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who took over the investigation. Cheasty met with Hoffa in northwest Washington at 11 p.m. on March 13, 1957. Cheasty handed Hoffa real documents from the Rackets Committee. Hoffa gave him $2,000. Agents moved in and arrested Hoffa with the documents. He was later indicted for bribery and conspiracy. Kennedy, who knew in advance of the sting, arrived at the federal courthouse that night for Hoffa’s arraignment. RFK later said Hoffa “stared at me for three minutes with complete hatred in his eyes.” The two conversed, arguing over how many push-ups they could do (Hoffa said he could do 35, Kennedy insisted he could beat that). Bobby’s wife, Ethel, had tipped off the press, and 50 reporters showed up, making it national news. Hoffa pled not guilty and raised $25,000 bail. RFK told a reporter he’d “jump off the Capitol” if Hoffa were found not guilty (which he did not do after Hoffa indeed was found not guilty that July).

While Hoffa’s arrest added momentum, the Rackets Committee returned to the daunting task of taking on the mammoth Teamsters Union at a time when unions were well respected in America since the labor vs. management turmoil of the 1930s. “With their power and prestige, the Teamsters also had public opinion pretty generally on their side as the hearings started,” McClellan later observed, “for millions upon millions of people who had witnessed the growth of unionism to maturity and respectability in our time simply refused to believe that ‘big labor’ could be grossly corrupt.”

On March 14, a day after Hoffa was arrested, Michigan Attorney General Thomas Kavanagh made national headlines after requesting that Chairman McClellan investigate how Teamsters officials had used wire recorders to listen in on secret grand jury hearings investigating alleged extortion by Hoffa in Detroit in 1953. Union witnesses who testified before the grand jury were wired with the tiny electronic recorders and microphones. Hoffa paid a wiretap expert, Bernard Spindel, $9,000 to bug Hoffa’s own office and buy the expensive concealed recorders.

The committee turned to questioning Beck in the Senate Caucus Room on March 26, 1957. The 62-year-old Beck, subpoenaed to testify in public, could no longer avoid it. He’d been Teamsters president since 1952. McClellan would later state that Beck “carried out with greedy shamelessness a campaign to enrich himself from the (union) treasury, and so neglected his duties that when he left office in disgrace, there were thugs and thieves in position of power” in the international union.

With research from the Teamsters’ books in hand, Bobby Kennedy asked Beck about the alleged misuse of $370,000 withdrawn from union funds, much of which had originated from the paychecks of its members for health care and pensions. Beck spent most of the money on building homes for himself and four associates in Seattle, but also on $40 shirts, football tickets, outboard motors, a freezer, golf clubs, his personal bills and those of his son and nephew. The committee discovered Beck received $24,000 in kickbacks from payments for decorating the union’s Washington headquarters, a sprawling building referred to as the “Marble Palace.” Beck had pressured the union’s locals across the country to buy toy semi-trucks bearing the Teamsters logo and took a share of $34,000 in profits. Beck further used union money to quietly take a personal gain from a national fund he started for the widow of a close friend. Ultimately, Beck, who grew visibly nervous during the proceedings, took the Fifth Amendment in answer to 140 questions from the committee.

Beck’s standing with the union crumbled in the aftermath of the public hearings. He had no choice but to step down as president. Months later in 1957, he was convicted of grand larceny and sentenced to 15 years in state prison for embezzling $1,900 from the sale of a Teamsters-owned Cadillac. In 1959, a federal judge imposed a five-year stretch in federal prison on him for evading $240,000 in income taxes.

In San Francisco on July 12, 1957, RFK told a meeting of the American Society of Newspaper Editors that flaws in federal laws regulating unions “will return to plague us with new Dave Becks unless we find basic solutions.” The Rackets Committee, he said, had received 40,000 letters of complaint alleging improper acts by unions. He added that “some form of federal action” was required to oversee unions to prevent misappropriation of welfare, pension and other union funds, rigged elections, the use of force and violence and organizational picketing and boycotts.

“In the International Laundry Workers Union,” Kennedy stated, “(secretary-treasurer) Jimmy James and several colleagues took $900,000 of welfare funds, and it was not a federal crime as the laws are now written.”

Grilling Hoffa

Hoffa, now the heir apparent to Beck as Teamsters president, started testifying in August 1957. Committee members alleged that Hoffa rose to his position in the union with the help of racketeers. Over three days, he claimed a loss of memory to 111 questions. On August 23, RFK accused him of obtaining, through New York racketeer Johnny Dio, the recording equipment used during the 1953 grand jury extortion probe. Dio and Hoffa, Kennedy said, successfully took over the New York City Teamsters by creating fake “paper” union locals with voting power but no members. When Hoffa said he could not remember the grand jury recordings, Kennedy replied, “It is beyond comprehension that you can’t remember this. You’ve had the worst case of amnesia the last two days I ever heard of.”

McClellan himself then cut Hoffa off, but made him listen to the evidence that committee investigators had uncovered: Hoffa had received $118,000 in loans, including a $25,000 no-interest loan from a man who borrowed $100,000 from the Teamsters and persons tied to employers with union contracts; Hoffa’s Detroit union local and a second local paid $155,000 to buy a home in Indiana once owned by Al Capone associate Paul “The Waiter” Ricca; Hoffa’s taxicab local in Chicago included as trustee Joseph Glimco, who was twice accused of murder and being an associate of Capone gang mobsters Anthony Accardo and the late Frank Nitti; Hoffa employed many people convicted of crimes such as armed robbery, kidnapping, larceny, bookmaking, throwing stench bombs and assault; and Hoffa permitted Dio to take an $11,000 payoff to prevent union organization of a factory in Pennsylvania. The committee determined that Hoffa’s Central Conference of Teamsters misused $2.4 million in union funds.

Still, Hoffa would leverage his strength with the Teamsters’ rank and file despite the allegations and negative press. In September 1957, the union conglomerate AFL-CIO, citing corruption, threw the International Brotherhood of the Teamsters out of the organization. Nonetheless, in October, 1,600 Teamsters members attending a national convention in Miami overwhelmingly voted to reject a report by the AFL-CIO laying out scores of corruption charges against Hoffa, Beck and other union officials. The convention, by a wide margin, then voted in Hoffa as president. “We are decent trade unionists and useful citizens,” Hoffa told attendees. “I have been beaten, threatened, abused and smeared.”

Hoffa persisted in painting the Rackets Committee as part of a conspiracy to persecute and “bust” labor unions. But the committee viewed Hoffa as a threat to the American labor movement. In their report to Congress, committee members declared that “(if) Hoffa is successful in combating the combined weight of the U.S. government and public opinion, the cause of decent unionism is lost and labor-management relations in this country will return to the jungle era.”

Exposing the Mafia

One remarkable day during the committee’s hearings took place on November 13, 1957. RFK and Senators on the panel questioned Bobby’s new friend at the Bureau of Narcotics, agent Joseph Amato. A 17-year veteran of the bureau, Amato was in charge of investigating mobsters and drug traffickers in New York City. Unlike FBI chief Hoover, the narcotics bureau knew full well about the existence of a national organized crime syndicate. By 1957, the syndicate was commonly referred in the news media as “the Mafia.” RFK decided to try to get Amato on the record about it.

Mr. Kennedy: Is there any organization such as the Mafia, or is

that just the name given to the hierarchy in the Italian underworld?Mr. Amato: That is a big question to answer. But we believe that

there does exist today in the United States a society, loosely organized,

for the specific purpose of smuggling narcotics and committing other

crimes in the United States.Mr. Kennedy: And that is what you consider the Mafia?

Mr. Amato: It has its core in Italy and it is nationwide. In fact,

international.

Their exchange about the “Mafia” would prove fortuitous. The next day, an incident famously dubbed “the Apalachin Summit” occurred in a small rural New York town of that name near the border of Pennsylvania. Dozens of upper-level mobsters – including bosses Vito Genovese, Joe Bonanno and Santo Trafficante, Jr. – scattered into the forest to evade police. About 60 were arrested. It turned out they were attending, or about to attend, a meeting of the national “Commission” of America’s La Cosa Nostra, on the property owned by their host, Buffalo mobster Joseph Barbara Jr. A parade of limousines with out-of-state license plates made local police suspicious, and state police joined in on the arrests. Hoover continued to resist acknowledging a national syndicate, but this time President Dwight Eisenhower ordered him to make a priority out of investigating organized crime. Hoover reluctantly acceded, preventing further embarrassment in the public eye, and soon instituted the FBI’s “Top Hoodlum” program of identifying alleged racketeers in major cities.

In an interview in the 1960s with New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis, RFK said that during the time he served as counsel for the Rackets Committee, the FBI “didn’t know anything about organized crime. That I knew. Because after the meeting at Apalachin, which 70 people attended, I asked for files from them on each of the 70, and they didn’t have any information, I think, on 40 out of the 70. Not even the slightest piece of information. Perhaps some news clippings. But nothing beyond that. I sent the same request to the Bureau Narcotics, and they had something on every one of them. … The Bureau of Narcotics had much more information … on organized crime in the United States than the FBI did. The FBI didn’t know anything, really, about these people who were the major gangsters in the United States. That was rather a shock to me.”

As the committee’s investigation entered 1958, RFK himself grew weary of pursuing the elusive Jimmy Hoffa. Hoffa recently got off on a criminal wiretapping charge in New York after the jury voted 11-1 to convict, and he won again at the retrial. The committee released a preliminary report on its 1957 hearings, recommending legislation requiring financial disclosures by unions and regular elections with secret balloting. Its investigators looked into hundreds of federal tax records, including those of Chicago crime boss Anthony Accardo, who pled the Fifth before the committee about his returns.

With Hoffa back in front of the committee in August 1958, RFK’s momentum started to falter. Kennedy had information from a Retail Clerks Union official, Sol Lippman, who said Hoffa threatened to kill him in 1955 if he did not merge the union with the Teamsters. Under questioning by Kennedy, Hoffa denied it.

Kennedy: Did you say anything about the fact that you could

have him killed in that office and nobody would know about it?Hoffa: I did not.

Kennedy: Did you say anything to the fact that he could be

walking down the street and could be shot one day?Hoffa: I did not.

When Kennedy said he had information to the contrary, Hoffa took the challenge. “Bring Lippman around here,” he said. But during a break, when RFK telephoned Lippman to encourage him to testify, Lippman said he did not want to aggravate Hoffa, and declined. “Okay, Sol,” Kennedy said. His aide Pierre Salinger later recalled that Bobby hung up the phone and said, “Shit.”

In September, after more frustrating back-and-forths with the recalcitrant Hoffa, McClellan reluctantly halted the hearing. RFK smiled wanly and admitted out loud he was “bushed.” Hoffa, peering at RFK, heard that. “Look at him, look at him!” Hoffa said. “He’s too tired. He just doesn’t want to go on.” It was partly true. Kennedy was drained after the long hearing with no breaks. “McClellan also was very tired,” Kennedy wrote in his notes at the time. “This year seems to have been tougher than last. Plodding grind … I feel like we’re in a major fight. We have to keep going, keep the pressure on or we’ll go under.”

To make matters worse, the Justice Department in 1958 did little with RFK’s referrals to prosecute alleged labor racketeers, contending there wasn’t enough to go on to bring cases likely to result in convictions. RFK aide Walter Sheridan said later that Justice Department prosecutors in the late 1950s “weren’t used to a Robert Kennedy, because they had never encountered one. They weren’t used to somebody who dug that deep, generated stuff that fast.”

Further, John Kennedy’s anti-racketeering legislation, the Kennedy-Ives bill, ran into trouble in 1958. The bill would require unions to hold secret ballot elections, file financial reports and disclose conflicts of interest to the Labor Department. It passed 88-to-1 in the Senate but was delayed in the House by Speaker Sam Rayburn on objections from Eisenhower, the Teamsters and management interests. Some who favored getting tough on unions thought it did not go far enough. The House rejected it 198-190, and it died.

Committee Winds Down

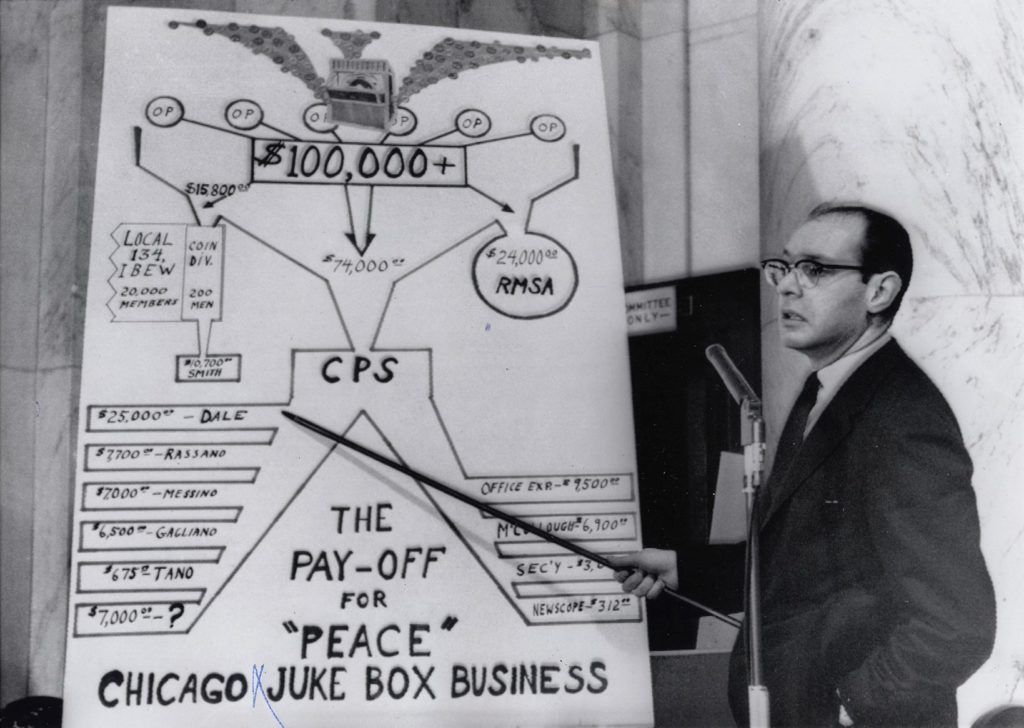

The hearings extended to a third year in 1959. In February, a jukebox machine operator from Brooklyn, Sidney Saul, wept as he recounted a beating he took in 1957 by three thugs who demanded he make Larry Gallo his partner. Larry Gallo, 30, and his brother Joey (“Crazy Joey” or “The Blond”) Gallo, 29, both reputed members of the Profaci crime family, followed Saul as witnesses but they refused to answer questions, invoking the Fifth Amendment. One question Joey Gallo rebuffed was whether he sought to control coin machines in New York City, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Ohio. Joey Gallo was alleged to have been one of the masked gunmen who shot Mob boss Albert Anastasia in a New York hotel barbershop in 1957. Joey at one point entered RFK’s office unannounced, chatted up his secretary and remarked, “Nice carpet ya got here, kid, be nice for a crap game.” Kennedy described Joey as “dressed like a grade B Hollywood gangster.”

On June 10, 1959, the Rackets Committee brought forward Sam Giancana, considered the No. 2 boss of the Chicago Mob under Accardo and who had attended the Apalachin Summit. RFK entered research into the record that in 1953, Accardo and Giancana appointed Anthony “Mr. Tom” Pinelli to run illegal gambling for Chicago’s syndicate, and John Formosa to operate its prostitution racket. Kennedy questioned Giancana about the Chicago gang branching out to oversee rackets in Lake County, Illinois, after corrupting its deputy county prosecutor. He also asked him about four unsolved murders in Chicago – one of a man who held Giancana’s $100,000 mortgage on a motel. Giancana, wearing dark sunglasses, laughed and deliberately fumbled his words while reading aloud his Fifth Amendments rights from a card in his hand.

“I thought only little girls giggled, Mr. Giancana,” Kennedy replied.

John Kennedy reintroduced the hoped-for labor reform legislation to come out of the Rackets Committee in 1959. But a competing bill, Landrum-Griffin, which many House members felt was stronger than John Kennedy’s, passed the House. Senator Kennedy helped build a compromise bill that won final passage by the Senate and House. The overriding aspect of the bill – ensuring fair, secret ballot elections within American unions – was its chief accomplishment. With his brother’s legislation passed, RFK wrote a letter to McClellan announcing his resignation from the Rackets Committee on September 10, 1959.

In the end, the committee with Kennedy as counsel held 300 days of public hearings, heard from 1,500 witnesses and published more than 20,000 pages of testimony. Its exposure of Dave Beck’s corruption forced him to resign as Teamsters president and helped send him to prison. RFK, from his televised clashes with Hoffa and other various hoodlums, was now a national figure. He turned his full attention toward managing brother Jack’s campaign as the Democrats’ nominee for president in 1960. Jack won the nomination, and narrowly defeated the Republican, Vice President Richard Nixon in November 1960. Jack, at 43 the youngest to be elected president, appointed RFK as his attorney general. Bobby, 35 years old, became the youngest attorney general since 1814. Now, as the nation’s top law enforcement officer, he revived his war on organized crime, this time with far more clout, the authority to request investigations from the FBI and subpoenas from federal judges, empanel grand juries and lead federal prosecutions as head of the Justice Department.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org