Organized crime roundup: U.S. seeks $12.6 billion in El Chapo drug proceeds, Peter Gotti seeks ‘compassionate’ release, eight convicted in ‘modern slavery’ racket in Britain and more

Cartel leader still complaining about jail conditions, including a noisy fan that keeps him up at night

Only days before a U.S. judge is expected to impose a long prison sentence on him for leading a major drug trafficking conspiracy, Mexican drug cartel kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman still claims to be suffering while in solitary confinement for the last 28 months, before and after his trial that ended in February.

Guzman’s latest beefs about his treatment – he’s repeatedly protested that his cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in Manhattan has poor air circulation and that noise from a fan affects his sleep – center on the prison’s “special administration measures,” uniquely strict rules placed on him based on his two infamous prison breaks in Mexico and the fact that he ran the Sinaloa cartel and ordered murders while incarcerated in his native land.

But he won’t be in the urban jail (also housing the wealthy alleged pedophile Jeffrey Epstein) for long. U.S. District Judge Brian Cogan on July 17 is set to announce Guzman’s sentence. A jury in February convicted El Chapo of 10 felonies, including operating a continuing criminal enterprise and conspiring to traffic drugs and launder money. The 62-year-old Guzman almost certainly will get decades if not life in a federal penitentiary, under maximum security.

In June, Guzman’s lawyers at his direction filed complaints alleging “inhumane” and “cruel” treatment at MCC. They said the crime boss needed six bottles of water a week because the tap water he drinks in his cell gives him headaches and ear pains. The prison, they said, does not allow him outdoors because an inmate had used MCC’s rooftop exercise yard to launch a failed escape try in 1981. In addition, the jail won’t let him use the commissary to buy food, toothpaste, soap or even the ear buds he wants to ease his earaches and help him sleep.

“Denying Mr. Guzman general commissary items serves no penological purpose,” defense lawyer Mariel Colon Miro wrote the federal court. “This restriction has no relation to the security concern, and only serves to punish Mr. Guzman, and further his sense of frustration and isolation.”

However, in a swift response, Judge Cogan brushed aside each of Guzman’s requests. Outdoor recreation can’t happen in order to “further the legitimate government objective of preventing him from escaping or directing any attacks on individuals who were cooperating with the government.” The judge noted that Guzman had been receiving six bottles of water a week since April. Further, he said, ear buds aren’t allowed at MCC anyway since inmates could not hear guards’ commands and might use them to ignore their commands.

Cogan also threw out Guzman’s argument for a new trial, based on a story in the online magazine Vice, which featured an interview with an unidentified juror days after El Chapo’s 11-week trial ended. The alleged juror claimed some on the panel, rebuffing the judge’s admonitions not to discuss or read about the case, read a news story about the trial (using a smartwatch to find it) and at least one reviewed Twitter messages written by a Vice court reporter.

The judge did observe that seven jurors had lied to him when he asked about exposure to media reports. But they did so fearing repercussions by the court, not because they had biases against Guzman that warranted a new trial. The incidents would not have affected their ability to render their verdict, which the judge said the jury based on the large amount of prosecution evidence and government witnesses testifying against Guzman in court.

More recently, on July 5, lawyers for the Justice Department sent a “letter motion” to Cogan, requesting, given Guzman’s conviction, a proposed order of forfeiture of money earned by Guzman from his criminal enterprises and drug sales – more than $12.6 billion. Under Title 21 of the U.S. criminal code, in narcotics-related crimes, the government is entitled to force defendants to turn over all of the property they gained from their criminal operations.

Prosecutors went to great lengths to arrive at the astronomical – if not record high in a federal drug case – cash total. They cited the 2007 criminal case U.S. v. Awad in which the government estimated the monetary value of a convicted drug dealer’s sales of illegal drugs “by multiplying the drug quantities by the narcotics street value, a figure that was ‘advanced at trial’ and remained ‘undisputed’ by the defendant.”

In Guzman’s case, they had plenty of specific information from his former drug-dealing colleagues in Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel who decided to turn on him as witnesses. In order to strike deals with the government, the witnesses agreed to testify as to how much in the way of cocaine, heroin and marijuana they delivered to Guzman for sale within the United States.

There was Jesus “El Rey” Zambada Garcia, who on the stand told how he, Guzman and other honchos of the Sinaloa cartel together invested in drug trafficking to share the risks and rewards: “It is one cartel, it’s one organization and they help each other when that help is needed.”

Since the jury convicted Guzman as a top leader in the Sinaloa’s criminal enterprise, prosecutors stated it follows that Guzman “is liable for all of the proceeds of the cartel’s drug activity.”

Other witnesses recounted the staggering quantities of drugs imported by Guzman’s cartel into the United States going back decades:

- Juan Ramirez “Chupeta” Abadia, a Colombian narcotics deliveryman and head of the Norte del Valle Cartel, testified he supplied at least 436 tons, or 436,000 kilograms, of cocaine for Guzman to sell in the U.S. The drugs arrived in three different ways – between 1990 and 1996, Chupeta flew in 200 tons of coke by plane, then 200 tons via boat between 1993 and 1998, and then used a submarine to ferret 36 tons in the mid- to late 2000s. One boat carrying 14 tons sank in a hurricane, so the total he provided – from Chupeta’s own ledgers used as evidence – was almost 400 tons.

- Miguel Martinez Martinez said in court that while based in Mexico City, he trafficked 423 tons of cannabis and two kilograms of heroin for Sinaloa between 1987 and 1993.

- Jorge Cifuentes, a Colombian drug pusher, told the court Guzman sent money to him in Ecuador to buy cocaine. Cifuentes then delivered six tons of the drug to Guzman, whose underlings sold it in New York.

- Jose Yusti Llanos, an associate of Luis “Don Lucho” Caicedo, supplied a sworn statement outlining Don Lucho’s delivery of 122 tons of cocaine to the Sinaloa group between 2003 and 2010.

- Pedro Flores testified that he and his twin brother trafficked about 53 tons of cocaine and 200 kilograms of heroin to Chicago at the behest of Guzman and Guzman’s partner, Ismael “Mayo” Zambada Garcia, from 2005 to 2008.

- Prosecutors put the estimated totals provided by Chupeta, Don Lucho and Cifuentes to Guzman at more than 528 tons of cocaine; then added 202 kilograms of heroin from Martinez and Flores and the 423 tons of marijuana from Martinez.

- That figure did not include the amount described by another drug seller, Jesus “Rey” Zambada Garcia (Mayo’s brother), who testified that between 1995 and 2008, he received 80 to 100 tons of Colombian cocaine a year in warehouses in Mexico City, or about 7,200 tons, for Guzman to sell across the border.

Justice Department lawyers then obtained from Chupeta, Cifuentes, Don Lucho, Flores and Martinez the estimated dollar values of the drugs Guzman ordered from them. The men adjusted the values based on timeframes and locations of the sales. From 1987 to 1993, for example, cocaine sold in Los Angeles for an average of $14,000 per kilogram, $25,000 in Chicago and $37,500 in New York.

The attorneys used an overall average price of $22,354 a kilogram of cocaine from the late 1990s to late 2008. Selecting the 528-plus tons of cocaine supplied by Chupeta, Don Lucho and Cifuentes alone to Guzman, they estimated El Chapo’s take at $11.8 billion. His heroin sales, at 202 kilograms at $55,000 apiece, came to $11.1 million; his marijuana, 423 tons at $2,000 a kilogram, added $846 million.

Guzman and his gang laundered this $12.6 billion, in U.S. dollars, back to Mexico and Colombia to repay the investors who supplied the narcotics, to cover employee payrolls and to buy communications devices and smuggling vehicles such as airplanes and submarines.

Much of it was in bulk cash amounts sent to Agua Prieta (a Mexican border town south of Arizona) in pickup trucks and mobile homes with secret compartments. From there, Guzman had cash loaded onto planes and flown to the city of Guadalajara or the central state of Guanajuato. Private jets flew from Tijuana to Mexico City carrying up to $10 million in cash per month. The smugglers transported other stacks of drug money hidden in shipping containers from supposedly “legitimate” businesses to warehouses in Mexico City, and then packed about $5 million at a time among ordinary merchandise in containers shipped to Colombia. They also stockpiled other bulk cash into private residences or deposited it into bank accounts used to pay expenses.

While Richard Donohue, the U.S. attorney of the Eastern District, and his aides formally asked Judge Cogan to issue the forfeiture order for the $12.6 billion, they did not explain exactly how Guzman would be able to pay back that sum. Meanwhile, Texas Republican U.S. Senator Ted Cruz thinks the money from the proposed forfeiture should go toward paying for a border wall with Mexico. The money “will go a long way toward building a wall that will keep Americans safe and hinder the illegal flow of drugs, weapons, and individuals across our southern border,” Cruz said in a statement.

Peter Gotti, aging Gambino don, wants out of prison

After serving 17 years of a 25-year sentence for a failed attempted Mob hit on Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, Peter “The Dopey Don” Gotti, reputed boss of New York’s Gambino crime family, is asking for “compassionate” early release from the federal pen.

Gotti’s recently appointed lawyer, James Craven, in a filing in federal court in Manhattan late last month, stated that Gotti’s long prison stay “has caused him to re-evaluate his thinking and reconsider his moral values. No longer does he try to justify his actions or defend the choices he made that brought him to prison.”

Craven claimed that Gotti, who’s pushing 80, is in poor health, with a laundry list of maladies from lung cancer to anemia, kidney disease, loss of sight in one eye and the early stages of dementia.

The lawyer wants the court to let Gotti out of prison for “compassionate” reasons, citing the First Step Act, federal legislation enacted last year that reduced the minimum age of early release for elderly prisoners from 65 years to 60 and the minimum time the elderly must serve their sentences from 75 percent to two-thirds.

Peter took over as Gambino boss with the death in prison of his brother John “the Teflon Don” Gotti in 2002. However, some did not respect Peter, saddling him with the nickname “the Dopey Don.”

Two years later, an anonymous jury in New York convicted Peter of racketeering conspiracy in seeking to kill Gravano by sending a two-man hit team, including Thomas “Huck” Cabonaro, to Arizona in 1999. Peter sought revenge against Gravano, whose detailed testimony in 1992 helped send John Gotti to prison.

But the hit men could not reach Gravano, who after being in witness protection, was charged with drug trafficking and received a lengthy term in prison (until his release in 2017). Gravano had been John Gotti’s faithful lieutenant for years before he turned state’s evidence after fearing the boss had marked him for death.

Eight guilty in alleged ‘modern slavery’ racket

In Britain, as many as 400 people from Poland were exploited by eight Polish nationals, who have been convicted in what the Crown Prosecution Service described as the “largest ever modern slavery prosecution” in the nation’s history.

The crime gang, including five men and three women ranging in age from 29 to 53, oversaw a human trafficking ring in Birmingham that took in about $3 million by forcing Polish immigrants to take menial jobs, seizing their wages, offering them little food and making them live in cramped and squalid housing, some without heat or running water.

Five in the gang received prison terms, ranging from three to 11 years, on human trafficking and forced labor charges. The court also convicted the remaining three.

The ring lured people living on the streets in Poland – many of them alcoholics, drug addicts and mentally ill – to come to the U.K. under the ruse of good-paying employment and comfortable living conditions. Some reported that ring members told them they would get about $160 a week, plus free food and housing.

However, once they arrived in Britain, victims worked 12-hour days in jobs such as picking onions, food processing, recycling and sorting parcels and were paid as little as $25 per week from their wages. The ring made them apply for government assistance accounts, from which the ringmasters stole the benefits. One woman said the ring members threatened to break her bones if she failed to work for them.

The gangsters spent the money extorted from the victims on luxury vehicles and other high-end products. Meanwhile, because of the lack of food, some victims had to eat at soup kitchens, where police first noticed them and learned of the slavery scheme.

At first, 88 people abused by the ring contacted authorities in Birmingham, and police estimate there are about 300 additional victims. In all, 66 witnesses testified in court.

BRIEFLY NOTED

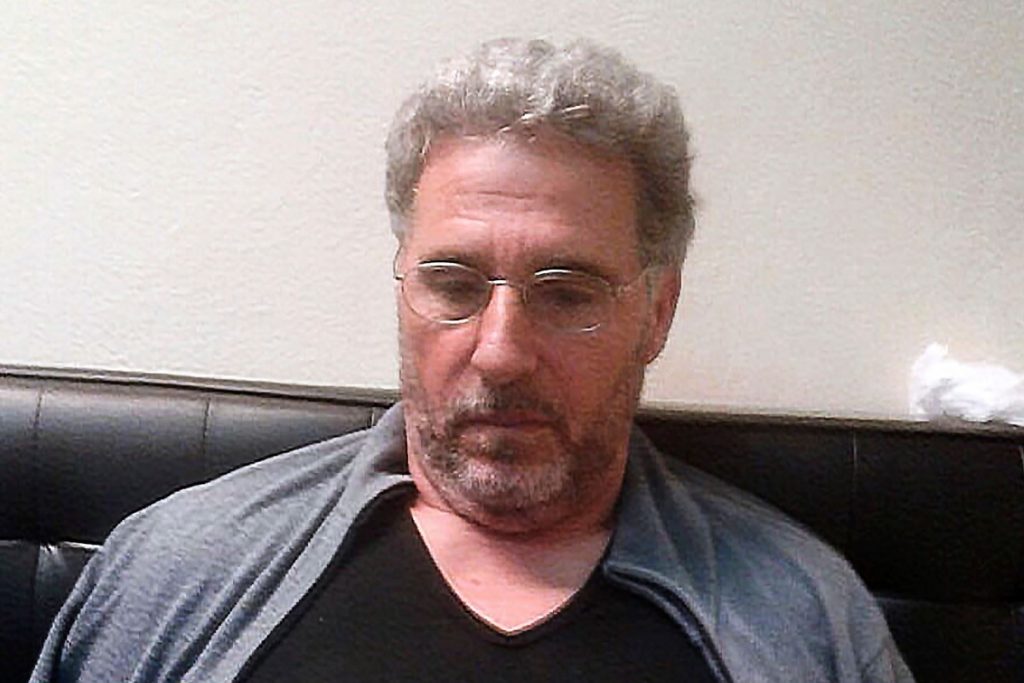

Rocco Morabito, the so-called “Cocaine King of Milan” and Italy’s most wanted member of the powerful ‘Ndrangheta crime group out of Calabria, remains at large after escaping from prison in Uruguay on June 23. Morabito, 53, jailed in Uruguay for the past two years pending extradition to Italy, broke through the roof of the prison with three other prisoners. They rappelled down by rope to an adjacent farm, where they robbed the owner. One of men was later recaptured. … Catherine Greig, the one-time girlfriend of the late Boston mobster Whitey Bulger, won release from federal prison in June. Grieg got nine years in the pen in 2012 for harboring Bulger for 16 years while authorities sought him to face drug dealing, extortion and murder charges. She’ll live in a halfway house in Massachusetts for two years left on her term. Bulger, convicted of 11 murders, died in a West Virginia federal prison last October after inmates beat him to death, allegedly because he was once a snitch for the FBI. … The editorial board of the Chicago Sun-Times newspaper has urged the mayor and city council to “build a firewall against the influence of organized crime” in response to a planned downtown Chicago casino that would rival Las Vegas Strip casinos, to open in summer 2020 or early 2021. The privately owned casino would have 4,000 gaming positions, from poker and blackjack tables to gaming machines, and sports betting, regulated by the Illinois Gaming Board. … Once a respected art dealer in Manhattan and now a notorious smuggler of antiquities, Subhash Kapoor has been charged in New York with trafficking in $145 million worth of purloined art works in an international racket going back 30 years. The U.S. government suspects Kapoor, in custody in India, of dealing in thousands of artifacts, including 2,600 items from six countries that authorities recovered from storage units in Manhattan and Queens, but $36 million worth remain missing.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org