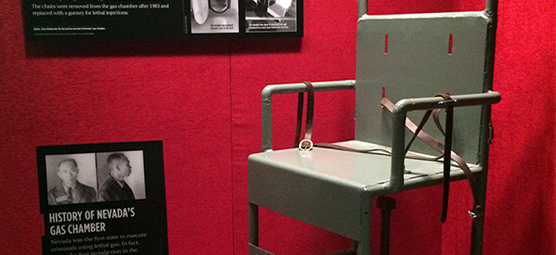

Nevada gas chamber chair goes on display

Jesse Bishop was final person to die in Nevada’s gas chamber

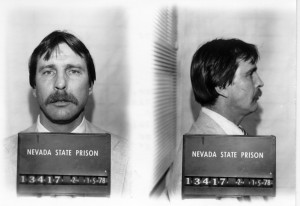

Jesse Bishop was ready to face death. The man convicted in the 1977 killing of a tourist during an armed robbery of a Las Vegas hotel-casino summarily dismissed all attempts by anti-death penalty advocates to delay his execution in the gas chamber at the Nevada State Prison in Carson City.

Moments after midnight on October 22, 1979, Bishop walked into the death chamber, turned to the left and took a seat in one of two metal chairs inside. Through windows he could see 14 witnesses, nearly all of them journalists, peering back at him. He recognized Las Vegas Sun reporter Mike Donahue and shook his head, as if to accept his fate. Bishop had befriended Donahue soon after the reporter covered Bishop’s arrest in 1977.

Appearing to avoid the people watching him, Bishop turned his head alternatively to the left and right, waiting. Then came a “pop” sound. Guards had pulled strings to release a pellet of hydrogen cyanide into a liquid acid bath beneath Bishop’s chair. Bishop, looking at Donahue, pointed downward. The deadly fumes rose. Bishop took a deep breath, deliberately inhaling the gas. His body shook, his head turned back and forth, his chest rose and fell. Within minutes, he stopped moving. A prison guard read an announcement informing witnesses that Bishop was dead.

Days later, a Las Vegas police detective released information that Bishop asked him to withhold until after the execution – Bishop’s claim to having been a hired hit man for years, murdering 17 or 18 people at the behest of Mafia figures he’d known through dealing drugs and using heroin.

Bishop, 46 years old, was the thirty-second and the last condemned man killed in Nevada’s gas chamber. On Wednesday, December 9, The Mob Museum will open an exhibit featuring the metal chair Bishop sat in during his execution. The chair is on loan from the Nevada State Museum in Carson City.

In 1983, the Nevada Legislature changed the state’s official method of execution from lethal gas to lethal injection. The chairs and sinks in the gas chamber eventually were removed and replaced by a gurney used to hold down prisoners condemned to death by injection. Though Nevada’s death penalty remains on the books, the last person executed in the state – via injection of a three-drug cocktail — was convicted murderer Daryl Mack in 2006.

Nevada’s history with the gas chamber is unique. Nevada was the first government jurisdiction in the world to approve lethal gas as a form of execution when the state legalized it in 1921. Up to then, prisoners sentenced to death had their choice – hanging or firing squad. The last person to be executed before then, a miner named Andrigi Mirkovich, chose to be shot. On May 14, 1913, at the state prison in Carson City, prison officials used a “shooting machine” equipped with three rifles to execute Mirkovich.

An influential book published in 1916 by Dr. Allen McLean Hamilton, a prominent New York toxicologist, helped lethal gas gain traction in Nevada. Hamilton argued that gas, such as carbon monoxide, would be more humane than other execution methods. The gas could be pumped into the prisoner’s airtight cell while the prisoner was asleep, producing a painless death. Mustard and other poison gases employed by Germany and France on battlefields during World War I, and new techniques for delivering the gas, also heightened awareness about its application for executions.

In early 1921, Nevada had not executed anyone since Mirkovich’s shooting death. Frank Kern, Nevada’s deputy attorney general who was persuaded by Hamilton’s views, brought the idea of lethal gas for executions to the attention of two freshman Assembly members, J.H. Hart, a Republican from Pershing County, and Harry Bartlett, a Democrat from Elko County.

Kern convinced them to introduce the so-called “Humane Death” bill making lethal gas the state’s sole method of execution. For some reason, the idea clicked and the legislation swept through both houses of the Legislature. A reluctant Governor Emmet Boyle, who opposed capital punishment, signed it into law. Nevada became the first government to institute lethal gas as its death penalty.

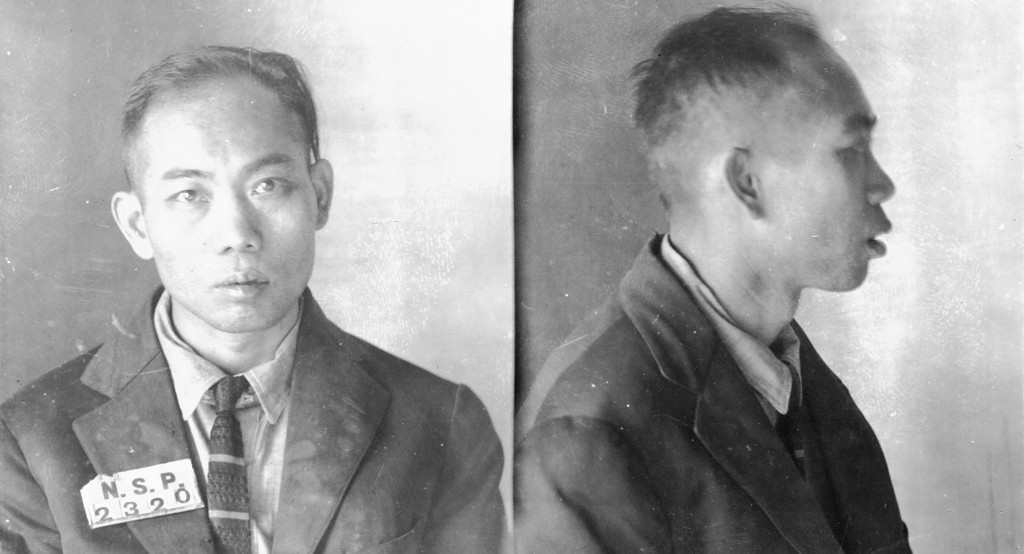

The first person sentenced to death was Gee Jon, an immigrant from China and member of the Hop Sing Tong, a San Francisco-based Asian organized crime group. Jon, on orders from his Tong, traveled 175 miles southeast of Reno to the mining town of Mina to shoot and kill an ethnic Chinese man involved with a rival Tong organization.

Tried and convicted of murder in Mineral County, Jon was sentenced by a judge to death by lethal gas. A federal court declined to review the case.

Nevada’s food and drug administrator chose to acquire hydrocyanic gas for Jon’s demise, citing its effectiveness as a poison. The state retrofitted a former barbershop at the state prison in Carson City to serve as the gas chamber. Officials ordered metal tanks containing the gas in liquefied form and a portable “autofumer,” similar to devices used to spray insects and other pests, to send the gas into the chamber.

On February 8, 1924, prison guards strapped Jon into a large wooden chair. Witnesses watched as the gas entered the small building. Some of the gas started to turn back into liquid and pool on the floor due to the cold winter temperatures and a malfunctioning heater.

Still, Jon stopped moving about six minutes after the vapors reached him. He was pronounced dead after a ventilator removed the remaining gas from the room. Jon’s death, the first legal execution by gas, made headlines across the globe. However, the problems with the gas embarrassed Nevada officials, who vowed to get it right. In the next lethal gas execution in 1926, with the aid of a new steam heater, the prisoner died in only two and a half minutes.

Nevada then set aside the former barbershop and built a new chamber in 1929. The pump system was discarded, but the same kind of gas would be used. This time, pellets of potassium cyanide would drop into a solution of sulfuric acid and water under the condemned prisoner’s chair. The chemical reaction from the pellets and liquid would create fumes of poison hydrocyanic gas, rising to the person’s head. The gas would block the body’s ability to process air, causing the person to suffocate.

Colorado took Nevada’s lead in 1933, establishing lethal gas for its executions. It became the second state to use it, killing a prisoner on June 22, 1934. Arizona quickly followed and sent its first convict to his death by gas on July 6, 1934.

Nevada built its third chamber in 1951. At the time, 11 other states had instituted lethal gas for executions. Nevada’s new chamber, modeled after California’s, had a sealed ship’s door to make it airtight, and two chairs. The first and only dual execution in the state’s history took place in 1954, when two men — convicted of murdering a man who gave them a ride in Northern Nevada in 1953 – died from breathing the hydrocyanic gas while seated together.

By the time Bishop died in that same chamber in 1979, 32 men had met their maker inside. Bishop himself had been the first to die in the chamber since 1961 (the death penalty was declared arbitrary and therefore unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972 and reinstituted in 1976).

But society changed again, and states began to favor death by lethal injection as more humane. Nevada switched from gas to injection in 1983. Eleven men died by injection on the gurney installed, with little room left, inside the chamber from 1985 to 2006.

As with most of the 30 other states that use lethal injections, Nevada’s protocol includes three drugs: sodium thiopental as an anesthetic, pancuronium bromide as a muscle relaxant and potassium chloride to stop the heart.

But the state prison in Carson City (which opened in 1862) closed for good in 2012, and the chamber shut down with it.

Recently, Nevada lawmakers declined to approve funds for a new death house. As of July, 78 prisoners were on the state’s Death Row at the state prison in Ely. But with no venue, no one is yet scheduled to die.

Meanwhile, Gee Jon’s old underworld Asian gang, the Hop Sing Tong of San Francisco, is back in the news. Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow, the former chief of the rival Ghee Kung Tong, has been charged in San Francisco with racketeering, gun and drug trafficking and ordering the death of the head of the Hop Sing Tong, Jim Tat Kong, who was killed in Mendocino in 2013.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org