Mobsters blamed for Election Day violence in New York City 90 years ago

Bloody battle over mayor’s seat results in election of law-and-order candidate Fiorello LaGuardia

Before a hotly contested battle for the New York mayor’s office culminated in a big win for a “law and order” candidate in November 1933, the typical vitriol and mudslinging on the campaign trail devolved into violence. This was not politics as usual. The Mob’s political influence was on the line, so out came the brass knuckles and blackjacks.

Political intrigues

Nationally, neither the Republicans nor the Democrats were in exceptionally good standing with American voters. This was the Great Depression, and there was plenty of blame to go around. Voters in New York’s five boroughs were presented with a rare opportunity to seriously challenge both dominant forces. This was especially intriguing for constituents fed up with the corruption and scandals inside the powerful Democratic machine of Tammany Hall.

Weeks before people headed to the polling stations, the press predicted that disruption and clashes would haunt the New York election.

The stage was set for major change. Investigations into New York City corruption began in 1930, spearheaded by Judge Samuel Seabury, and the allegations led straight to the mayor’s office.

Under mounting pressure, Mayor Jimmy Walker resigned in September 1932 and fled the country. In his place stepped Joseph McKee, but that was short-lived, and John O’Brien filled the position. Challenging the old system, with a special focus on reducing the Tammany influence, two third-party ticket options emerged: the Fusion and Recovery parties.

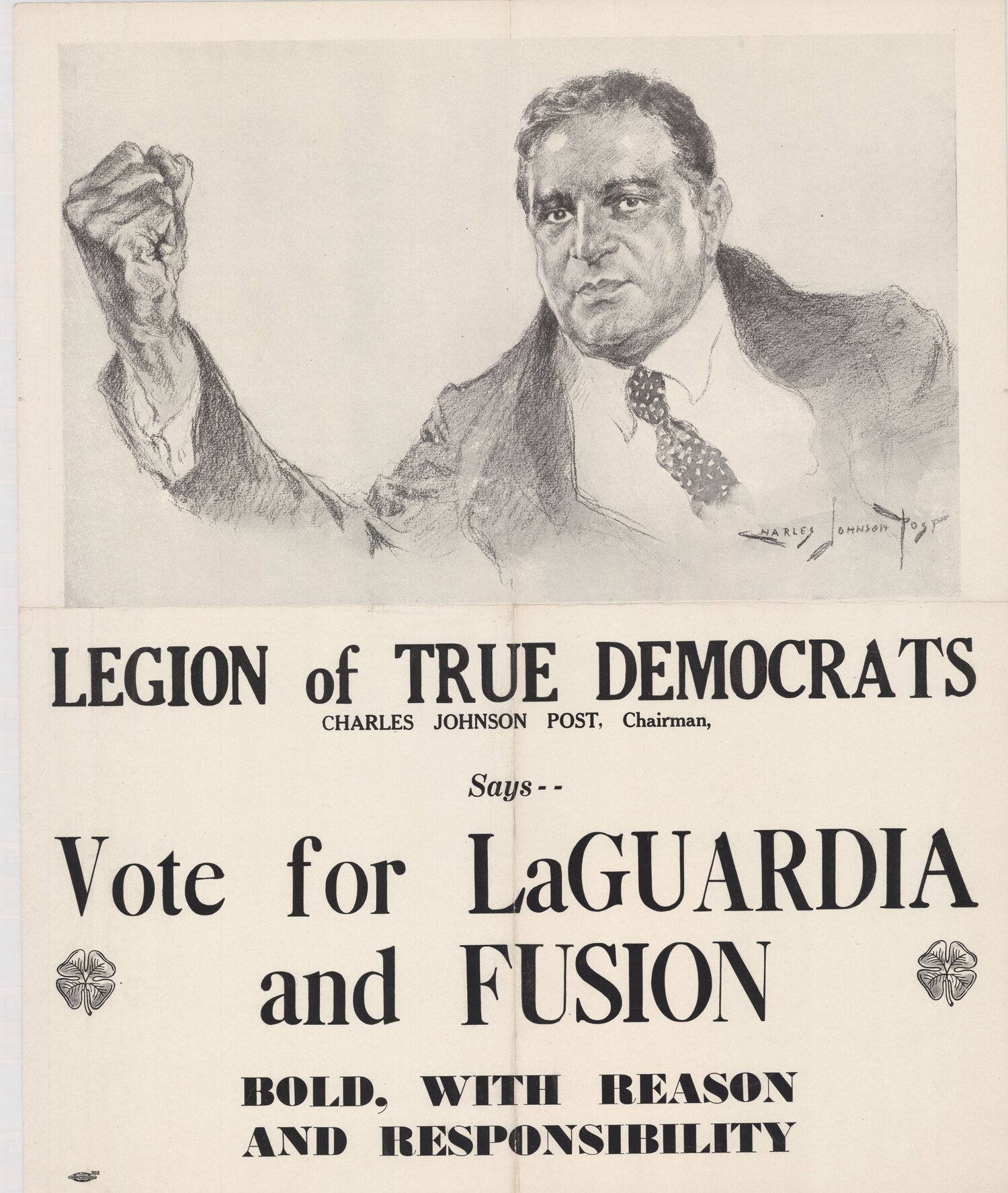

To the surprise of many, the maverick movements gained an almost unprecedented following as more than 50,000 voters registered with these new parties. The Fusionists essentially tried to harness the best of both major parties and “fuse” them into one incorruptible and righteous entity.

Meanwhile, Republicans tussled over who should be their candidate. Enter Fiorello LaGuardia. The staunch tough-on-crime Republican wasn’t anybody’s first choice, but according to the book Others: Third Parties During the Great Depression, strong endorsements turned the tide in his favor. “As it turned out,” author Darcy G. Richardson writes, “the GOP acquiesced to the highly regarded Seabury and the City Fusion leadership at almost every step in the candidate-selection process.”

Drama unfolded on the Democratic side as well. McKee, viewed as a viable candidate for any party, entered the race late and ran on the Recovery party ticket. Both new parties were granted approval just weeks before the election.

The O’Brien campaign tried to distance itself from former Tammany Mayor Walker. O’Brien, however, was not viewed as a particularly strong contender, and spent much of the campaign defending his record and principles.

Blood in the streets

The two-pronged threat against Tammany gained momentum as Election Day approached. Efforts by concerned factions commenced to “dissuade” voters from making the “wrong” decision, and bloodshed soon followed.

“Fist fights, slugging and violence splotched the nation’s largest city today as more than 2 million voters determined whether Tammany Hall would control municipal government for four more years,” according to an Associated Press report on November 7, 1933.

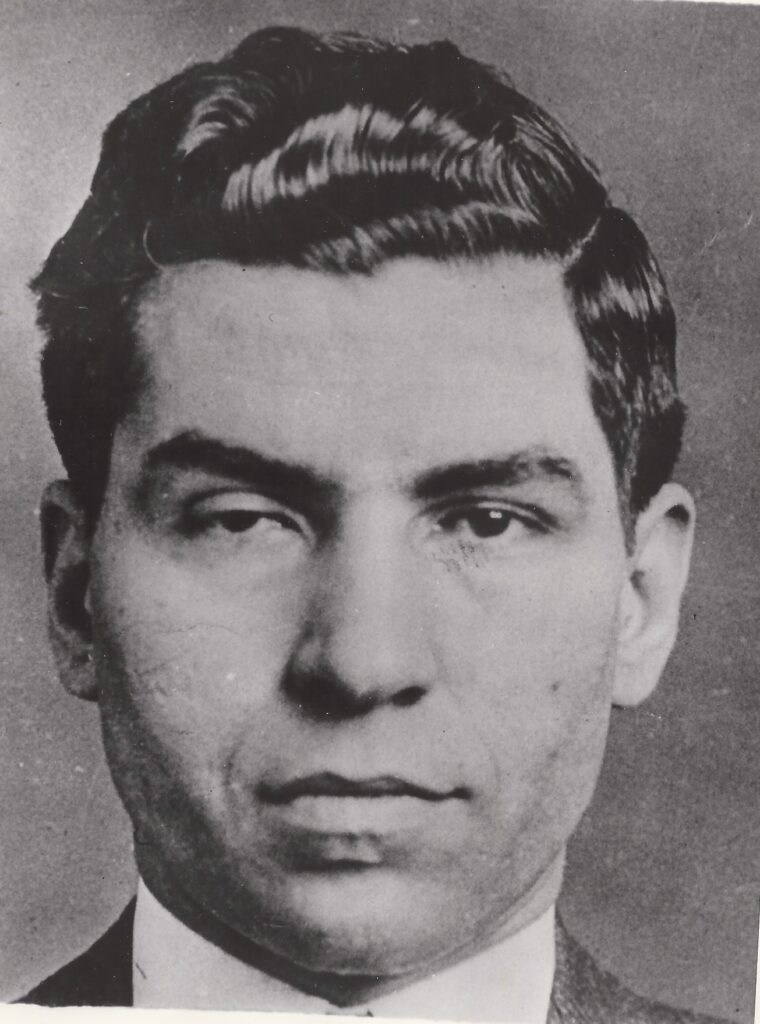

News reports described groups of people attacking opposing groups at rallies and speeches leading up to November 7. On Election Day, the bloodletting was blamed almost entirely on roving bands of men who accosted voters, poll workers and campaign staff throughout Manhattan. A handful of daily newspapers spiced up the copy with colorful, sometimes gratuitous prose. One of New York’s papers went a step further, calling out and laying blame on two specific Lower East Side mobsters, neither of whom were household names, at least not yet.

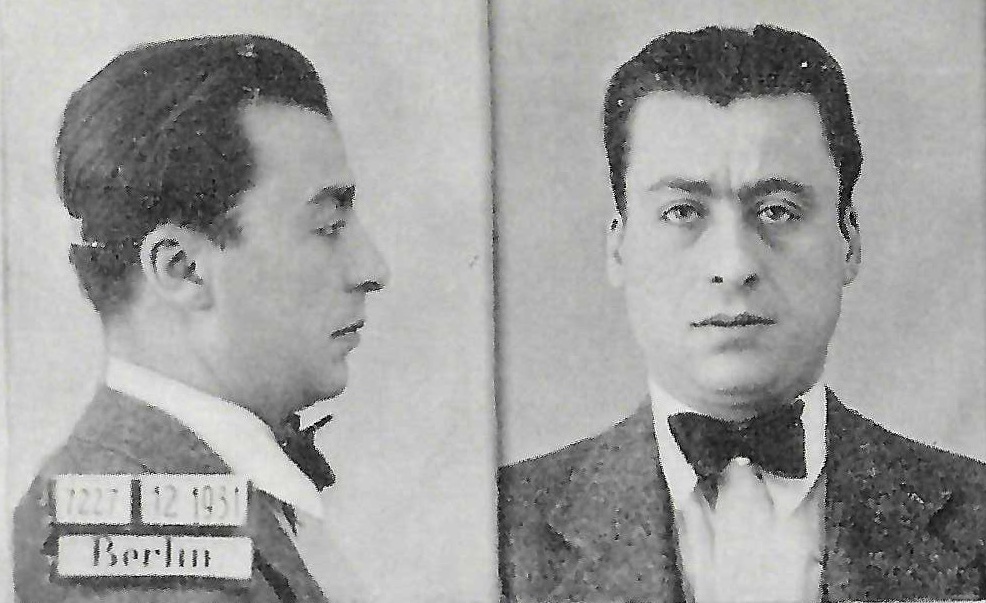

According to the New York Daily News, coordinated transgressions were carried out by underlings of August Del Gracio and Charles “Lucky” Luciano. “Gangster Del Grazzio, who has inherited the name Little Augie because of his prominence as a hoodlum, was in charge of the Tammany strong-arm squad at the Baxter and Hester corner,” said one Daily News report.

Luciano’s minions, the paper alleged, mobilized around Public School 21 at the intersection of Elizabeth and Spring streets. “During the morning Lucky’s gangsters slugged Fusion, Socialist, Recovery and Communist voters without discrimination. … Policemen on duty turned their backs on the beatings.”

Winners and losers

Luciano and Del Gracio both grew up in Lower East Manhattan and were associates in the underworld. Although Luciano was a familiar figure to local law enforcement and newspapers (the Daily News had covered him quite a bit since 1928), he was not yet well known outside the city.

Conversely, Del Gracio had already earned international media notoriety as a world-traveling drug trafficker. Earlier that year he was named to the Top 10 list of traffickers by Egypt’s Narcotics Bureau and the League of Nations. Augie’s full story and role in the Mob has never gotten much traction in the broader annals of organized crime history, but back in 1933 he was probably as good a choice as any when putting a name or a face to a crime.

Arguably, both men were plausible culprits. Thomas Hunt, publisher of Informer Journal, says LaGuardia’s well-known anti-organized crime stance certainly would have been strongly opposed by Luciano and his associates, but where the allegations of direct involvement in the day’s chaos originated is anybody’s guess. “Possibly, Fusion spokespeople fed that information to the press,” Hunt theorizes. “If the press was going to invent a story about the person in charge of muscling voters, I’m not sure they would have decided on Lucania.” (Lucania is the actual spelling of Luciano’s name.)

Despite the barbarity of its efforts, and regardless of who ordered it, the Mob didn’t chalk up much in the win column that day. Richardson summed up the rather unusual voter turnout: “Astonishingly, more than 1,119,000 New Yorkers voted for mayoral candidates, including La Guardia, on independent or minor party tickets that year, while barely a million voters pulled the Democratic and Republican levers.”

All the coercion and head-busting tactics apparently couldn’t stop the fast-moving winds of change. In the end, the Fusion-backed candidates did well across the board. LaGuardia won the race with 858,551 votes. McKee came in second with 604,045 votes. Tammany fell to a hard third: O’Brien was unable to carry even one of the five boroughs.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad and LUCKY, a gangster graphic novel.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org