Leave no trace

Long history of criminals mutilating their fingerprints to try to evade capture

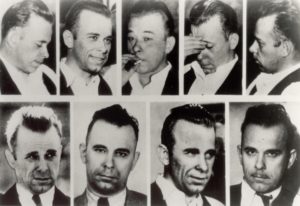

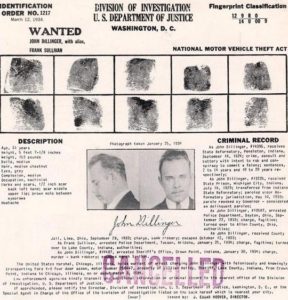

In 1934, John Dillinger was one of America’s most wanted. He was in hiding in Chicago and looking for a way to escape arrest. He turned to plastic surgery, hoping to transform his face and erase his former identity. His lawyer introduced him to Wilhelm Loeser, a German-born physician involved in the narcotics trade. Loeser agreed to change Dillinger’s face and fingertips for $5,000.

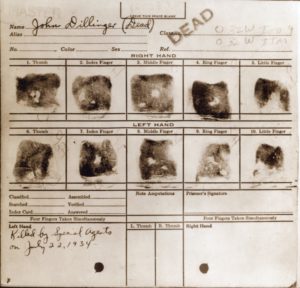

To modify Dillinger’s prints, Loeser cut away the outer layer of skin, the epidermis, and treated the fingertips with hydrochloric acid. He then scraped away the remaining visible ridges. Dillinger could not use his hands for days, but his fingertips grew back mostly intact. The centers were obscured, but the edges of his prints were still recognizable.

In the end, the surgeries didn’t help Dillinger. On July 22, 1934, FBI agents were waiting for him when he walked out of Chicago’s Biograph Theater. When he ran into an alley, they shot him dead.

Fingerprint mutilation may seem extreme, but Dillinger is one of many criminals who have attempted to hide their prints. Another Chicago gangster, Alvin “Creepy” Karpis of the Barker-Karpis gang, attempted to remove his prints that same year. He went to Joseph Moran, the doctor of choice for Prohibition-era gangsters. Moran was quite successful in removing Karpis’ prints, although the ridges were still faintly visible. Karpis later struggled to obtain a Canadian passport thanks to his barely recognizable prints.

Fingerprint mutilation is nearly as old as the practice of fingerprint identification. Fingerprints link people to their arrest records and outstanding warrants. Obliterating them seemingly provides a clean slate. People use many different methods to try to remove fingerprints. Cutting or sanding them off or burning them with cigarettes or acid is common. Underworld physicians even assist with surgical procedures. But can people really get rid of their fingerprints that easily?

One of the first criminals to try it was August “Gus” Winkeler, a murderer and bank robber associated with Al Capone. His prints from 1933 indicated cutting and slashing. His prints were still identifiable, but he did successfully modify them. One changed so drastically it appeared to be a loop instead of a whorl.

Fingerprint identification began in the late 19th century, as scientists began to realize the skin on our hands and feet is unique. Human hands are covered with skin that has patterns of hills and valleys, known as friction ridges. Friction ridge skin, which is formed in the womb, leaves impressions on any surface that it touches. People leave latent prints, ones created by the oil on their skin and not clearly visible to the naked eye, everywhere. Individual fingerprint patterns are unique — even identical twins have different prints. Before DNA profiling, fingerprint analysis was the most effective way to identify a person.

In the 1880s, anthropologist Sir Francis Galton first classified fingerprints patterns. Galton’s three categories of prints — loops, whorls and arches — are still used today. He determined that no two sets of prints are exactly alike. He also verified earlier findings that fingerprints do not change with age.

By 1911, fingerprint analysis was helping to convict murderers. Thomas Jennings was the first murder suspect convicted on the basis of fingerprint evidence. His print was found in wet paint on a porch railing at the scene of the crime in Chicago. Investigators compared it with fingerprints on file from a past burglary charge and determined a match. Four experts testified that the collected print belonged to Jennings.

Fingerprint mutilation continues today. In 1995 Florida officials arrested a man with mutilated prints under the name Alexander Guzman. Officials manually reconstructed the prints in order to analyze them. After searching the FBI’s Automated Fingerprint Identification System, they linked the prints to the arrest records of Jose Izquierdo, a drug criminal. Izquierdo had cut a Z-shaped incision into each finger, lifted and switched the two flaps, and stitched them together.

In 2010, the FBI reported fingerprint mutilation was on the rise. Most modern cases are connected to illegal immigration or the drug trade. Massachusetts State Police recorded at least 20 individuals arrested with modified prints in 2009. One arrest led to three men charged in a conspiracy to aid illegal aliens evading detection through the surgical removal of fingerprints. The surgeon in question, Dr. Jose Elias Zaiter-Pou, allegedly charged patients $4,500 to mutilate their fingerprints. He was sentenced to 12 months and one day in prison.

Even as fingerprint mutilation becomes more sophisticated, some criminals take an informal approach. In 2007, a man arrested for car theft successfully bit off his fingertips while in custody to avoid identification. There have been similar attempts in recent years, including a Florida man in 2015 who attempted to chew off his prints while in the backseat of a patrol car. The surveillance video of his unsuccessful attempt circulated on the internet that year.

So how well does fingerprint mutilation work? Fingerprints are hardy. The ridges visible on the epidermis run into the deeper dermis layer of skin. In order to truly obliterate a fingerprint, every layer of skin must be removed. An article in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology from 1935 recommended at least one millimeter of skin must be removed in order to ensure ridges do not regenerate.

Today, increasingly refined digital databases exist. Using the FBI’s database, only a few distinct ridge details are needed to establish a match. Mutilated prints are harder to analyze, but even the faintest ridges or the tiniest edges of an original fingerprint can be used to match fingerprints with a known set.

Investigators are trained to pay closer attention to mutilated prints. A person willing to go to such lengths to obscure his identity is suspect. In 2014, the Next Generation Identification System, a new FBI biometric database, combined fingerprint records with palm prints, facial recognition, iris identification and other characteristics. These comprehensive records make it easier and quicker to identify people.

With these new methods of identification, fingerprint mutilation becomes even less advantageous. It is better advised for those determined to commit a crime to simply wear gloves.

There is technically no law against altering your fingerprints, but Dr. Zaiter-Pou’s conspiracy conviction may serve to discourage most would-be fingerprint mutilators.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org