Fearless Las Vegas journalists Jeff German, Ned Day left lasting legacies

The Milwaukee natives fearlessly exposed mobsters and public officials

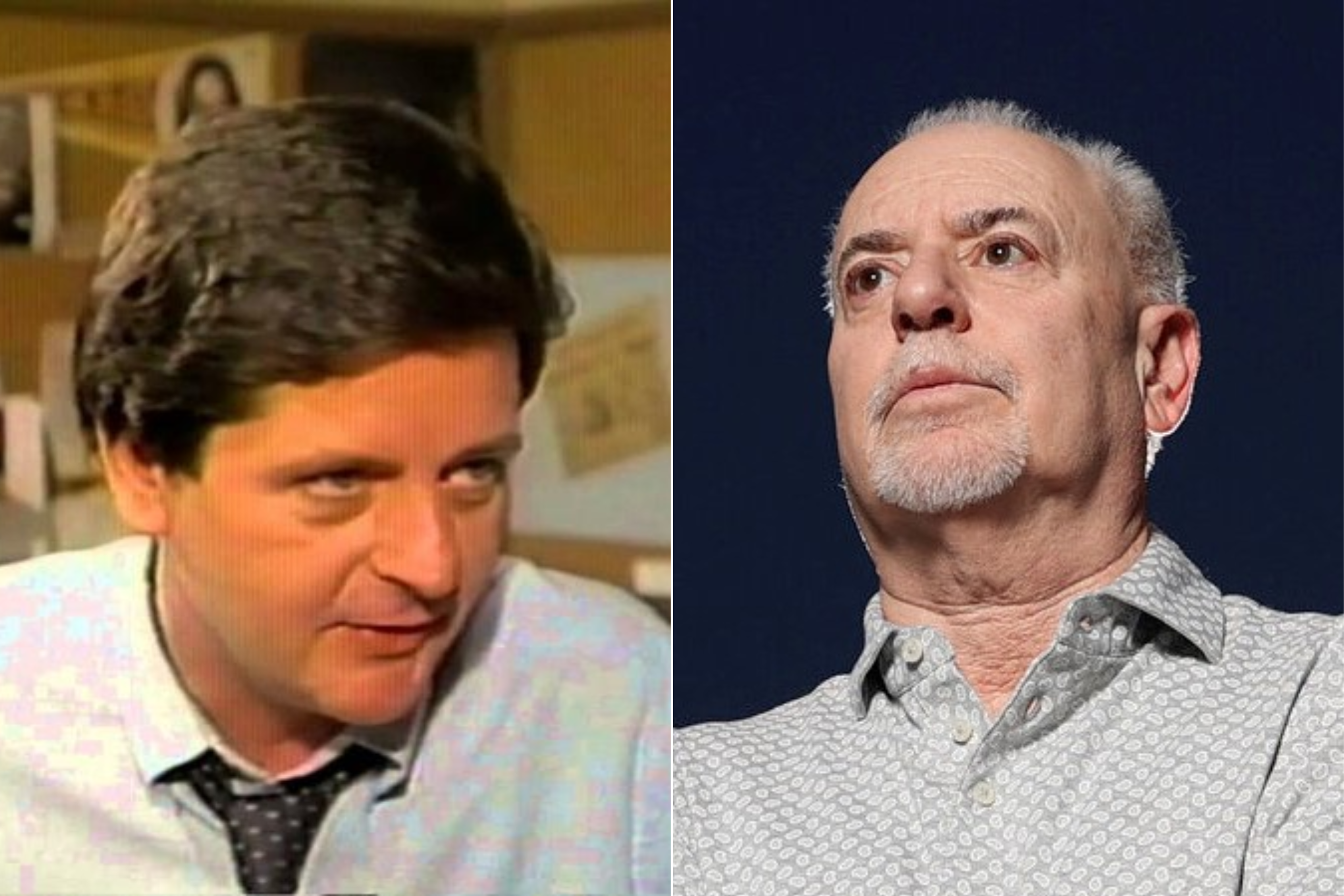

Las Vegas reporters Jeff German and Ned Day had more in common than a dogged approach to digging out major news stories.

Both were from Milwaukee, both covered the Mob during its explosive downward spiral in Southern Nevada, and both were targeted by people they exposed in their reporting.

Both also reported and narrated two of the most important works of journalism ever on organized crime in Las Vegas.

‘Mob on the Run’

Day, a print and broadcast reporter, worked with News Director Bob Stoldal and others at KLAS, the CBS affiliate in Las Vegas, to produce the 1987 documentary The Mob on the Run.

The documentary covers more than 50 years of Mob involvement in Las Vegas but especially draws attention to the era later portrayed in the movie Casino, starring Robert De Niro, Sharon Stone and Joe Pesci. The events dramatized in the movie mostly occurred in the 1970s and early ’80s.

During that period, Chicago bookmaker Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal ran the Stardust and three other Argent Corporation casinos for Midwestern Mob families, with Tony “The Ant” Spilotro serving as the Chicago Outfit’s overseer in Southern Nevada. In the movie, released in 1995, De Niro and Stone portray characters based on Rosenthal and his wife, Geri. Pesci’s character is based on Spilotro.

Over the course of German’s newspaper career, he worked at the two main dailies in Las Vegas, the Sun and Review-Journal, covering courts, politics and organized crime for more than 40 years.

Like Day, who received news tips from people on both sides of the law, German cultivated a variety of sources who knew they could trust him with confidential information.

‘Mobbed Up’

German’s decades-long knowledge of the city, from the streets to casino boardrooms, added important details to the true crime podcast “Mobbed Up: The Fight for Las Vegas,” which he researched and narrated in a partnership between the Review-Journal and The Mob Museum.

Among other aspects of Las Vegas’ Mob past, including funding arranged by the Teamsters Union’s Jimmy Hoffa for casino construction, the eight-part second season of “Mobbed Up” examines organized crime’s influence at the Aladdin hotel-casino on the Strip.

The podcast also looks at the feud between entertainers Wayne Newton and Johnny Carson over ownership of the Aladdin after the Mob was pushed out of the resort, located where the Planet Hollywood hotel-casino now stands.

Killed in knife attack

In early September, Las Vegans were stunned to learn that the 69-year-old German had been stabbed to death outside his home.

Right away speculation arose about who might have done it, including a sense that the killer could have been someone German had written about over the years.

During more than four decades, German exposed corruption and wrongdoing at the highest levels of state and local government. A competitive reporter, he also covered Spilotro and other underworld operatives in Las Vegas.

Early in his career, German saw first-hand, in a minor but telling encounter, the arrogant influence that mobsters wielded in Las Vegas.

One Saturday night, German and a colleague saw Spilotro and Hollywood actor Robert Conrad in a bar near the Upper Crust pizzeria, a Mob-run restaurant east of the Strip. The reporters asked their server to tell Spilotro they wanted to buy him a drink. “We didn’t know any better,” German later said. The server went to Spilotro and spoke to him, then returned with a stern message: “You don’t send Mr. Spilotro drinks. He buys you drinks first.”

“It was like he owned the town,” German said in a July 2021 interview on Nevada Newsmakers with broadcast host Sam Shad. “It was eye-opening.”

German had other experiences with Mob figures that turned out to be more serious.

In the early 1980s, after he had written about a Justice Court warrant officer who collected juice money for the Mob, the court officer, a former professional boxer, threw a drink in German’s face during an event at the Sands hotel-casino on the Strip. After dousing German with the drink, the former boxer punched him in the face. The incident resulted in German receiving four stitches to his lip.

Decades later, when first hearing the news of German’s death this year, some wondered if a long-ago Mob revenge motive might have been a factor in the Sept. 2 fatal stabbing.

As it turned out, the investigation went in a different direction.

With Review-Journal reporters working to help solve their colleague’s violent death, the focus shifted to a little-known Clark County elected official, Robert Telles.

German had reported on accusations that Telles created a hostile work environment in the office, including bullying and other misconduct. Only months before German was killed, Telles lost a bid to win re-election as Clark County public administrator.

Based on neighborhood surveillance video and other evidence, Telles, 45, was arrested and charged with murder. He is being held without bail while awaiting a trial.

German’s killing led to strong condemnation from news organizations globally. The nonprofit group Investigative Reporters and Editors, working with the Review-Journal, has set up a Jeff German Fund for Investigative Journalism “to help continue the kind of game-changing investigations German devoted his life to producing.”

“Jeff’s senseless death evoked a strong resolve from journalists across the country that we will not be intimidated,” IRE Executive Director Diana Fuentes said. “This fund will help journalists follow in Jeff’s footsteps, holding those in elected office accountable to the people they serve.”

From ‘street scuffler to street reporter’

Day also faced abuse from people he covered as a reporter, first at the small Valley Times newspaper in North Las Vegas and then at the Review-Journal and KLAS.

The Valley Times has since gone out of business, but the muckraking Day, arriving from Milwaukee in 1976, helped turn the paper into a must-read, often scooping the larger Sun and Review-Journal.

The son of a national champion bowler named Ned Day, the younger Day, who briefly dabbled in professional bowling, ultimately drifted into “a netherworld of bars, pool halls and gambling” in Milwaukee, according to veteran KLAS reporter George Knapp, a friend and colleague of Day’s in Las Vegas.

Shortly after Day died in a 1987 while snorkeling in Hawaii, Knapp documented Day’s life and career in a series of broadcasts for the Las Vegas news station.

As Knapp pointed out, Day had become a bookmaker in Milwaukee and a bartender at nightclubs controlled by the Balistrieri crime family. At a topless bar, Day met a former Miss Nude America. The two were married in 1972.

Still in Wisconsin, Day later was arrested for attempting to pass bad checks to pay off a bookie. According to one of his later newspaper colleagues in Milwaukee, Day during this period described himself as a gambler and pimp.

With his marriage falling apart, however, Day quit bartending and bookmaking, and, as Knapp reported, sold his diamond pinkie ring. Day took a night job delivering pizzas for a local restaurant coincidentally named Ned’s Pizza. He enrolled at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and landed a job at a weekly newspaper, transitioning, as Knapp put it, from “street scuffler to street reporter.”

Then things took a turn for the worse.

In April 1976, Day’s girlfriend, a stripper and part-time prostitute, was strangled to death along with her 10-year-old daughter, Day’s goddaughter. Day dug into the killing, even snapping a photograph of the man later convicted of using a bicycle-lock chain on the daughter and a lamp cord on the mother. The daughter died trying to protect her mom.

Move to Las Vegas

That same year, at the suggestion of friend, Day moved to Las Vegas at age 31, escaping a troubled past in Milwaukee. In Las Vegas, he applied for a job at the Sun but was turned down. He made his way to the Valley Times and was hired at $150 a week.

Linda Faiss, who worked with Day at the Valley Times before becoming a Las Vegas public relations executive, said the Wisconsin native immediately felt at home in Southern Nevada.

With the experiences he’d gained on the streets in mobbed-up Milwaukee, a town whose Major League Baseball team name, the Brewers, underscores its beer-making heritage, Day was a natural fit in free-wheeling Las Vegas.

“He liked the glitz, the glitter, the bimbos, the lounge lizards,” Faiss said. “He liked the movers and shakers, and the fact that we were such a young, upstart city. I think that was his kind of place.”

From the start, Day called out those operating unscrupulously but unscathed in the town’s good ol’ boy protective tradition. The Mob was a favorite target.

Over time, Day’s face had begun to show up on underground wanted posters distributed in at least one bar that Knapp and Day popped into.

Risks of the job

The pressure on reporters was intensifying, as German experienced at the Sands. Day felt it, too.

In July 1986, Day’s uninsured three-year-old Volvo was firebombed on a night when he fortunately was not in it, though he later lamented the scorching of his golf clubs in the backseat. In a taped interview, Day fired back.

“It does not demonstrate a great deal of menace to sneak up in a parking lot in the dead of night and attack an unarmed car,” Day said. “If that’s the best that they have to offer, they don’t scare me at all.”

The firebombing was never solved, yet Day understood the streets and knew his reporting was having an impact on the mobsters whose presence had created what Knapp called a “fear factor” around town.

During an April 2017 panel discussion at The Mob Museum, Knapp said the firebombing was the best day of his friend’s life.

“To Ned it confirmed that he was getting under people’s skin,” Knapp said.

A year later, on Sept. 3, 1987, Day died at age 42 while vacationing in Hawaii with girlfriend Mary Ottman. Knapp reported that the local coroner determined “heart disease was the culprit,” and while rumors persist that foul play might have been involved, those suspicions, Knapp said, are “almost certainly unfounded.”

“There was no foul play,” Knapp said on the air.

In explaining what led to his friend’s death, Knapp said Day was at the “high end of virtually every category for heart disease.” Though attempting to lead a healthier life by then, Day for years had been a heavy drinker and smoker whose diet, consistent with a reporter’s hectic schedule, mainly consisted of hamburgers and other fast food.

“There were many people who may have wanted him dead,” Knapp reported, “but they were not to blame for what happened at Hanauma Bay.”

Apparently no serious threats had followed him to Hawaii. Those who knew Day said he would not have been intimidated by threats anyway. A year before the firebombing took place, his car was vandalized. He remained undaunted and continued a streak of hard-hitting investigations.

In The Money and the Power: The Making of Las Vegas and Its Hold on America, authors Sally Denton and Roger Morris wrote that Day “refused to back down, sometimes seeming to flaunt his invulnerability, convinced that he had become too public a figure to be killed.”

“If something happened to me,” Day said, “then 60 Minutes and ABC’s 20/20 — Geraldo Rivera and all those jerks — are going to be all over here like they were in Arizona, where reporter Don Bolles was murdered.”

Bolles had reported on Mafia infiltration and land fraud in Arizona before dying in June 1976 after his car was bombed in the Hotel Clarendon parking lot in Phoenix.

During Day’s September 1987 funeral service at Guardian Angel Cathedral in Las Vegas, former Nevada Governor Grant Sawyer noted that the community underwent a sense of loss at Day’s death.

Though Day by this time was making good money, he spent much of it and was living a lifestyle that reflected his journalistic defense of the have-nots. Sawyer said Day owned no property and lived in an apartment described as “scruffy,” according to the Las Vegas Sun. Day had his telephone disconnected three times the previous year for failing to pay the bill.

The outpouring of support at Day’s funeral was an indication of the reporter’s contribution to the community, Sawyer said. “He defeated the pompous and self-righteous and become the most influential man in Nevada,” the former governor said.

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. Today, he is a senior reporter for Gambling.com. The Mob in Pop Culture blog appears monthly.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org