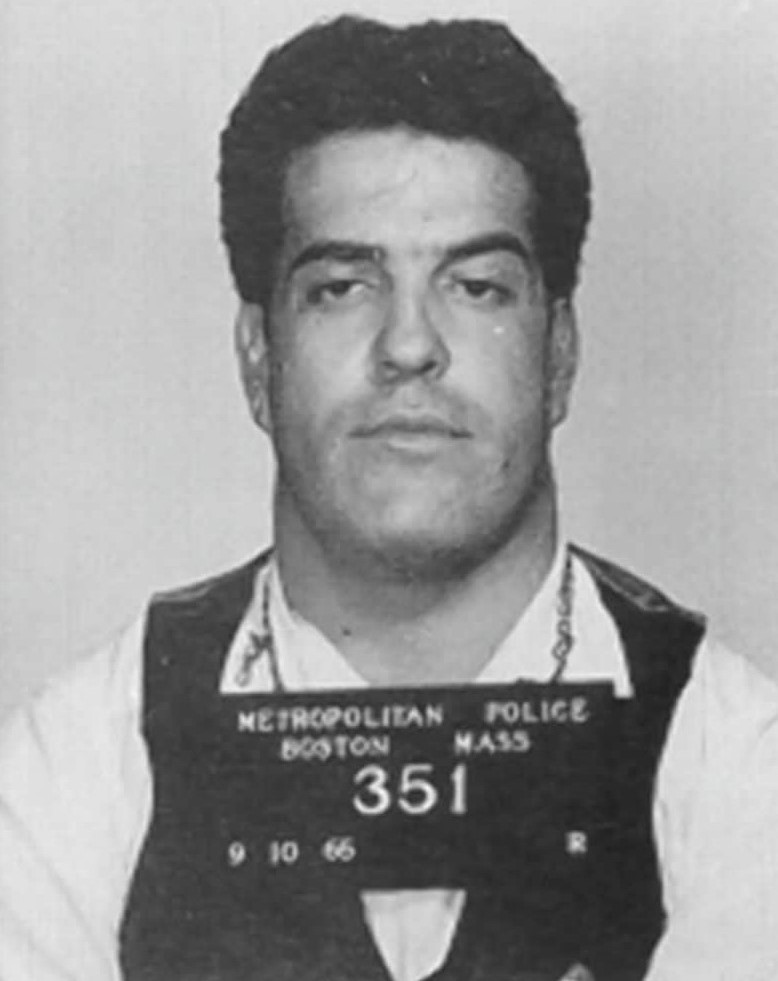

Joe “The Animal” Barboza: No. 4 on list of Top 5 most notorious Mob hitmen

Killer for Patriarca crime family earned nickname for vicious acts

In this fourth installment in our series on the Top 5 most notorious Mob hitmen, the focus shifts to the Boston area in the 1960s, when several dozen people died in an inter-gang war and the feds went too far in courting a turncoat.

Our selections are limited and the methodology subjective. The richness of the stories, the amount of dependable research material and how the individuals fit into the greater context of their times mattered more to us than the number of victims they chalked up.

The Top 5 are: “Machine Gun” Jack McGurn, Abe “Kid Twist” Reles, Roy DeMeo, Joe “The Animal” Barboza and Giovanni Brusca.

Trapping ‘The Animal’

Based on his years as a crazed hitman, street loan collector and intimidator for Raymond Patriarca’s New England Mafia, Joe “The Animal” Barboza should have recognized he might have been set up. Add to that the fact he’d been an FBI informant and trial witness years earlier and the first person admitted into the federal Witness Protection Program.

But on February 11, 1976, Barboza, once assigned by the feds to live in Santa Rosa, California, under the name Joe Denati, went to visit his old friend and Mob associate James Chalmas in San Francisco’s sleepy Sunset District. He had been set up — by Chalmas, who earlier tipped off Patriarca family underboss Gennaro “Jerry” Angiulo.

Angiulo sent caporegime Ilario M.A. Zannino and Mob soldier Joseph Russo to watch for when Barboza left Chalmas’ residence near the corner of 25th Avenue and Moraga Street. As Barboza approached his parked car and pulled out his key, a van rolled up fast and Zannino and Russo at almost point-blank range fired four shotgun blasts at him through an open door.

The two men responsible for Barboza’s murder remained unknown until the FBI listened to bugged conservations by Angiulo and Zannino in 1981 in their social club near the Old North Church in Boston. Zannino spoke respectfully of Russo in orchestrating the Bay Area hit, calling him “a brilliant guy.” Zannino also implicated himself as a shooter in the murder.

“We clipped Barboza. I was with him [Russo] every [expletive] day,” Zannino told Angiulo. “He made snap decisions. There, he couldn’t get in touch with nobody. And he accomplished the whole [expletive] pot.”

For Angiulo, the hit on Barboza represented the end to The Animal’s life as a “stool pigeon” for the federal government. Barboza had agreed to turn informant and testified against both Angiulo and Patriarca in 1968. To safeguard him, the feds created the Witness Protection Program. Not only that, Barboza became the first Cosa Nostra associate to provide testimony in court against the Mob.

Barboza, who legally changed his name to Baron in 1964, was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1932 to a family of second-generation Portuguese immigrants, a fact that always made him feel left out, since his lack of Sicilian or Italian blood meant backhanded acceptance into the mobster fold only as an associate, never a made man.

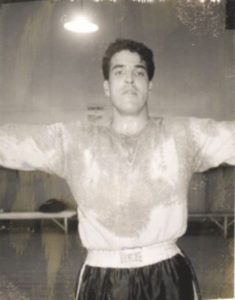

Over the years, the strong, hulking, jut-jawed Barboza developed into a living, breathing Hollywood caricature of a Mob thug. He tried his hand unsuccessfully as a prizefighter, but the brutal skills he learned came in handy. Burglary and other arrests as a young man got him eight years in prison in the 1950s.

In court in 1968, he claimed he started off as a gang enforcer and loanshark in about 1961. At first he worked for the mostly ethnic Irish Dudley Street Crew. Barboza boasted of making $5,500 a week on the “vig” or interest on his cash loans given out to inveterate gamblers and others on one street corner in Boston.

Sadistic enforcer

As an intimidator, Barboza won the nickname “The Animal” for the viciousness he displayed on the street to collect late loan payments. He once chewed off part of a man’s cheek and spit it out during a fight and gnawed on a piece of a man’s skull that blew off when he shot him.

In a 1970 television interview, Barboza said: “I’d stab guys after 14 weeks who still continued to hide” to avoid making payments.

“You know, I’d stab them in the face,” he said calmly. “I’d stab them in the legs, I’d stab them in the arms, I’d stab them in the chest.”

In the 1960s, when Patriarca allied his smaller Providence-based gang with Irish and independent ethnic mobsters, the bloody McLean-McLaughlin gang war raged in Boston. In 1965, in desperate need of hitmen and enforcers to gain control for his Mob family in Boston, Patriarca recruited Barboza. The 34-year-old used his talents to blunt the work of the independents. He claimed to have killed 26 people during the more than three-year war that claimed nearly 50 lives.

Barboza’s brief purge allowed the Patriarca family to again dominate the streets and criminal rackets such as gambling and loansharking. Then in 1966, police arrested Barboza on gun charges when officers pulled him over and discovered an arsenal in his car. In jail, he expected Patriarca to post his enormous $100,000 bail, but the boss refused. When some of Barboza’s crime associates raised more than $80,000 toward it, Patriarca had three of them killed and their money taken. The boss also took over The Animal’s loanshark racket. Barboza heard of it all in jail.

He soon received a visit from Boston-based FBI agents Dennis Condon and H. Paul Rico, who played for him an illicit recording of Patriarca calling him a “bum” and “expendable.” He agreed to turn as an informant in exchange for immunity, safety for his family and to get even with the Mob. For him, being a stoolie was his only option. The Patriarca family of New England, for which he had faithfully collected, beat and killed, had betrayed him. He felt double-crossed by his former equals, whom he claimed threatened to kill him, his wife, young child and other members of his family. In fact, after authorities transferred Barboza to Thacher Island off Cape Ann and arranged for his transportation over water to the mainland to testify in court, Patriarca allegedly sought to hire snipers on speedboats to try to take him out.

Barboza’s testimony about Patriarca ordering the slaying of an independent dice game operator, Willie Marfeo, resulted in a murder conspiracy conviction in 1970 for the Mafia boss and two others. Patriarca got 10 years in prison. The sentencing was a huge blow to the Patriarca leadership and a big victory for the FBI and Justice Department. By then, about 50 of the family’s 75 members were dead, in prison, charged with a crime or informants.

Miscarriage of justice

But few knew back then just what had to happen for it all to come about. While naming names for Massachusetts prosecutors, Barboza had been a willing pawn in one of the most shocking miscarriages of justice ever perpetrated by the FBI, with the full knowledge of then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. In a separate murder case, he lied under oath, at the request of corrupt FBI agents Condon and Rico, on the stand in state court against six defendants — all Mob associates — accused of the 1965 murder of minor league hood Edward Teddy Deegan in the city of Chelsea outside Boston.

State prosecutors, based almost solely on Barboza’s uncorroborated and perjured testimony, and unaware of the FBI’s actions, won convictions of the six men in Deegan’s murder, when none of the defendants in fact took part in the killing. The FBI and Barboza framed them. Two defendants received life sentences, the other four got the death penalty, although no one was executed. In exchange, the FBI protected Barboza’s close friend, the veteran hitman, Jimmy “The Bear” Flemmi, from state murder charges in Deegan’s homicide. The FBI used Flemmi’s brother, hitman Steve “The Rifleman” Flemmi, to convince Barboza to perjure himself. Barboza consented, saying he would not provide information that might cause his best friend Jimmy “to fry.”

It took decades to finally sort things out from the official cover-ups. In 2002, the House Committee on Government Reform looked into the FBI’s use of Barboza, Jimmy Flemmi and other murderers as federal informants. In a scathing 1,800-page report released in 2004, the committee stated that Barboza and Jimmy Flemmi actually killed Deegan, but Hoover and the FBI, seeking to preserve both men within the new Top Echelon informant program to gain intelligence on the Mob, allowed the innocent defendants to take the fall. The FBI, no doubt under political pressure to catch and prosecute mobsters amid the deadly Boston gang war, cynically played a “devil you know” game with irrational and dangerous criminals in hopes of gathering evidence against the top bosses, with embarrassing consequences for the agency.

In its report, the committee included these events in its chronological list:

“On March 19, 1965, FBI Director Hoover or his staff was provided information about the Deegan murder. Hoover was told that Jimmy Flemmi was involved in the murder. The information recorded contradicts Barboza’s trial testimony.”

“On May 7, 1965, Director Hoover or his staff was told that microphone surveillance of Raymond Patriarca captured the following: ‘information had been put out to the effect that Barboza was with Flemmi when they killed Edward Deegan.’ This contradicts Barboza’s trial testimony.”

“June 4, 1965 — Director Hoover made an inquiry about Jimmy Flemmi.”

“June 8, 1965 — [FBI Agent] Rico talked to Jimmy Flemmi about financial payments.”

“June 9, 1965 — Director Hoover’s office was informed by memorandum that Jimmy Flemmi had committed seven murders, including the Deegan murder, ‘he is going to continue to commit murder…’ but ‘the informant’s potential outweighs the risk involved.’”

The committee concluded that, “[b]eginning in the mid-1960s, the Federal Bureau of Investigation … began a course of conduct in New England that must be considered one of the greatest failures in the history of federal law enforcement.”

What the FBI did first with Barboza and Jimmy Flemmi, the committee reported, provided a “foundation to assess” what the agency in Boston did from the 1970s to 1990s, when disgraced FBI agent John Connelly used informants and in the process covered up for mobsters Steve Flemmi and Whitey Bulger. That pair committed at least 19 gangland murders during that period.

The Barboza saga just got worse and worse before his death. In 1970, sent to Santa Rosa in witness protection, he met a small-time crook named Clay Wilson, who told him about money and valuables he’d stolen during burglaries. Barboza wanted part of the spoils and argued with Wilson. While walking in the country with Wilson and two women, Barboza shot and murdered Wilson, then put his body under a tree stump. He scared the women into not talking about it.

Arrested for the murder soon afterwards, he bluffed about recanting his false testimony in Boston, which prompted FBI agents to rush to California to serve as character witnesses and assist in Barboza’s bogus plea that he shot the unarmed Wilson in self-defense. Even then-U.S. Attorney Edward Harrington, who headed the FBI’s organized crime strike force in Boston (and later appointed a federal judge) showed up with Rico and Condon to testify in court for their informant who helped put away Patriarca. Barboza, a turncoat’s turncoat, had threatened to retract his testimony in Boston multiple times to gain leverage for himself. The pressure worked in his California state court case. He got five years to life on a reduced second-degree murder charge.

In his first parole hearing five years later, the feds sent more “character” witnesses to argue for his release, and it worked again. Barboza got out of prison in November 1975. He moved to San Francisco. Four months later, shotguns fired on orders from the Patriarca family put an end to the charade. Barboza’s death certainly must have delighted Patriarca, who was released in 1974 after only four years in prison for Marfeo’s murder, and died a free man, of natural causes, at the home of his paramour in 1984.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org