In 1980s New York, the Mob had its hands in everything — even a museum

The Westies gang siphoned hundreds of thousands of dollars from the Intrepid Museum in New York City

This is The Mob Museum, but it has never been a mobbed-up museum.

As surprising as it may seem, that is exactly what the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum, located in Manhattan, unwittingly became in the 1980s. Members of an Irish American Hell’s Kitchen gang infiltrated the museum, siphoned off hundreds of thousands of dollars in ticket sales and placed union members in no-show jobs.

This lucrative racket might have gone on for years if the Intrepid hadn’t filed for bankruptcy in July 1985. Bizarrely, the museum’s bankruptcy filing had little to do with the Mob scheme, but its skimming was discovered during financial investigations connected to the bankruptcy proceedings. It was a complex arrangement, one of many cooked up by the Westies, based on the time-honored Mob penchant for union racketeering. And it’s a reminder that organized crime infects so much of American history.

Now known simply as the Intrepid Museum, the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum opened in 1982. Organized as a nonprofit, the institution operated as a museum of American military and maritime history. The museum is housed in the USS Intrepid, an aircraft carrier from World War II moored at Pier 86 along the Hudson River. Located in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of West Side Manhattan, the museum was firmly established in the Westies’ sphere of influence.

In the 1980s, that sphere was a ruthless and violent one. The Westies were a relatively small outfit — estimates range from 20 to 60 members. In the 1960s, Mickey Spillane (not the author) took control of the Hell’s Kitchen rackets. In addition to bookmaking and loansharking, the gang controlled unions at Madison Square Garden, the New York Coliseum and the docks.

On August 20, 1976, Spillane’s main muscle, Eddie Cummiskey, was shot and killed at the Sunbrite Bar. Up-and-comer Jimmy Coonan was ready to take over the neighborhood — Spillane’s loss was Coonan’s gain. Spillane began to retreat from his rackets. Coonan had been working with established loan shark Ruby Stein, who also worked with “Fat Tony” Salerno of the Genovese crime family, and he stepped in to control some of Spillane’s business. Coonan also recruited Mickey Featherstone, a violent and emotionally troubled Vietnam War veteran born into a working-class, Irish American family in Hell’s Kitchen.

Coonan also began meeting with Gambino crime family hitman Roy DeMeo and one of his crew members, Danny Grillo. It was probably this relationship more than any other that set up Coonan for underworld success. In May 1977, Coonan orchestrated the deaths of Stein and Spillane, and just like that, a new generation took charge.

According to author T.J. English in his 1990 book The Westies, DeMeo killed Mickey Spillane as a present to Coonan. This brought Coonan to power and shifted the Westies’ trajectory. By working with DeMeo, he ultimately agreed to an alliance with the Gambino family within Hell’s Kitchen, although some of his crew were hesitant about the connection.

Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, the Westies were plagued with prison sentences, but this never upended their stranglehold on Hell’s Kitchen and the West Side docks. When a new museum was under development along the Hell’s Kitchen waterfront, it may have been inevitable that the Westies would become involved.

The USS Intrepid launched in 1943 as an aircraft carrier. It was used in World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War before being decommissioned in 1974. Many wished to see her preserved, and, in 1978, New York real estate developer Zachary Fisher established the Intrepid Museum Foundation. The Intrepid came home to Pier 86 in June 1982, two months before the museum opened officially on August 3.

The Museum was staffed in part by members of the Local 1909 chapter of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), the largest maritime workers’ union. ILA Local 1909 assembled in the 1960s to represent marina and boatyard employees during the 1963-1964 New York World’s Fair. In 1968, it shifted to representing employees for the Kinney Parking System at the North River Passenger Terminal, which by the 1980s also handled parking for the Intrepid Museum.

One of the Westies’ more lucrative connections during this period was Vinnie Leone, business manager for ILA Local 1909. Coonan and Featherstone worked with Leone, who was also connected to the Gambino family. This arrangement benefited them all, and union racketeering helped the Westies stay in power while Coonan and Featherstone served prison sentences in the early 1980s. In fact, both were incarcerated when the museum opened in 1982. In February 1984, Leone was found dead, but the Westies maintained control of Local 1909.

The ILA controlled about 30 staff positions at the museum, including ticket sellers, engineers and maintenance personnel. Featherstone’s wife, Sissy, was one of the ILA members employed as a ticket seller. Sissy devised a scheme wherein she and a few other women saved previously sold tickets, resold them and kept the profits. Later, Kenny Shannon, a Westie allegedly involved in Leone’s death, became the museum’s timekeeper. That’s when Sissy Featherstone went from corrupt ticket agent to no-show employee.

In addition to the staff actively employed in this criminal enterprise, the union also charged several no-show jobs to the museum. No-show jobs are just what they sound like — paid positions for which the employees have no actual duties and do not even need to show up to earn their pay. No-show jobs are a form of corruption found in political and corporate environments and are particularly common in labor unions. They are a common way for mobsters to earn what appears to be legitimate income without working.

No-show jobs can be lucrative. The month the Intrepid opened, Bobby Huggard was given a no-show job as a gift for perjuring himself in a murder trial. He earned $227 a week, or roughly $725 in today’s dollars.

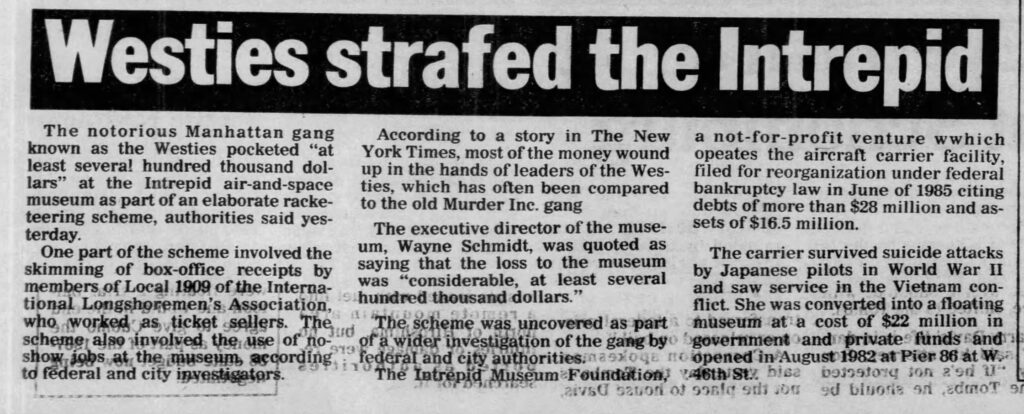

Ultimately, the museum’s executive director, Wayne Schmidt, reported that the museum lost $100,000 to $120,000 annually to the Westies’ combined racketeering activities. In the early 1980s, this loss was still unknown to Schmidt and other foundation leadership, but it was far from the only financial setback for the new museum.

In the first few years of operation, the museum struggled in part because of its location in a rundown area, lack of other nearby attractions and near-constant construction in the area at the Javits Center. In July 1985, the Intrepid Museum filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The organization had failed to raise adequate funds or attract enough visitors. According to an April 16, 1987, New York Daily News article, the Intrepid hosted 400,000 guests annually, but the expenses for running a museum in a 40-year-old aircraft carrier amassed quickly. Schmidt blamed poor attendance and poor weather. In the bankruptcy filings, the foundation listed $16.5 million in assets and $28.4 million in debt.

In March 1987, five ticket sellers were let go from the museum after the box-office skimming scam was discovered. Schmidt claimed these positions were filled with no input from him or his team. The following month, investigations revealed the museum had been subject to extortion and theft schemes by the Westies that expanded beyond the initial five fired workers.

In an April 4, 1987, article in the New York Times, journalist Selwyn Raab outlined information obtained from federal and New York City investigators. Raab, who later authored Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires, was an investigative reporter at the time known for his extensive coverage of New York organized crime. Federal and local law enforcement had begun conducting entirely coincidental investigations into the Westies and their criminal activities in the late 1970s.

On March 26, 1987, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Rudolph Guiliani and Manhattan District Attorney Robert M. Morgenthau announced the indictments of 10 members of the Westies. The Westies faced charges under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO). Their crimes included eight murders, numerous attempted murders, kidnapping, loansharking, extortion, gambling and drug dealing. These indictments came out of a deal with Mickey Featherstone, who offered to testify against his crew when faced with 25 years in prison. Featherstone likely was also motivated by a falling out with Coonan related to his management of the gang.

In 1988, Coonan was sentenced to 75 years in prison. He remains incarcerated although he has since been granted a mandatory release date of June 1, 2030. Eight other Westies were also convicted. Mickey Featherstone has been in the Witness Protection Program since he became an informant.

The Intrepid Museum is still open. It restructured and had a second chance after its brush with bankruptcy. The neighborhood no longer suffers from the blight associated with it in the 1980s, and the museum is one of many popular attractions in the area today.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org