The Hollywood legend, the Mob and the jukebox racket

How actress Debbie Reynolds unwittingly fell into a Mob scam

The venerable actress and singer Debbie Reynolds, who died last week at age 84, was a risk-taker for decades when it came to investing her money after her movie career took off in the 1950s. She lost millions of dollars, to her regret, thanks to misplaced trust in her three callow spouses. “All of my husbands have robbed me blind,” she remarked in 1999.

In one of her ventures in the mid-’60s, producing short films for an audio-visual jukebox called the Scopitone, she unknowingly became entangled with, and ultimately victimized by, a group of hidden investors that included members of New York’s Genovese crime family — gambling racketeer and loan shark Vincent “Jimmy Blue Eyes” Alo and underboss Gerry Catena. The influential William Morris Agency in New York, which provided top-flight talent for Mob-connected entertainment businesses from coast to coast, had secretly set up Alo, Catena and the Genovese family in the emerging Scopitone racket back in 1961.

Reynolds entered the fray in 1964, relying on the guidance of her business partner and manager Irving Briskin, a former B-movie producer for Columbia Pictures. She and Briskin agreed to use their Harmon-EE Film Productions company in Hollywood to produce music films for Scopitone cinema jukebox machines. They signed the production deal with the maker of the machines, Chicago-based Tel-A-Sign Inc. Both Reynolds and Briskin liked the idea of shooting song-length films with American singing stars, including Reynolds herself. Neither realized that Alo and Catena controlled Tel-A-Sign and Scopitone.

Early version of MTV

The Scopitone saga began in the late ’50s when the French company Cameca modernized the concept of “Soundies,” coin-operated jukeboxes built in the United States in the late ’30s that showed sound films of music acts. They were discontinued because of the demand for raw materials during World War II. The new Scopitone coin machines, made in France and then Italy, debuted all over Europe with films of mainly French pop stars in 1960. The six-foot-tall, 500-pound Scopitone jukebox offered a list of color films, about three to three and a half minutes long, of song-and-dance routines shown from an internal projector onto a 26-inch screen.

The next logical step from Europe was the rich American market. But who would obtain the U.S. rights for Scopitone machines from Cameca? Enter George Wood, who headed the New York office of William Morris, a major talent agency for leading actors, singers and other performing artists. The agency represented the likes of Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Gregory Peck, Jimmy Durante, Milton Berle, Jack Lemmon, Mickey Rooney, Sophia Loren, Clint Eastwood and many more stars. It also used its roster of celebrities to browbeat film producers with demands for a 10 percent fee off the top if they wanted to sign one of its stars. Among the TV shows then involving Morris clients were the top-rated “The Real McCoys” and “The Rifleman.”

In 1961, Wood steered his way into securing the American rights to Scopitone. At the time, there were about 500,000 audio jukeboxes in the United States, typically for a nickel a song. The massive flow of coins from most of them had been a lucrative racket for organized crime families in New York, Chicago and elsewhere since the 1930s. To get started in Scopitones, Wood needed financial backing. He had close ties to a motley crew of New York and New Jersey organized crime types discreetly behind closed doors at William Morris. But law enforcement officials were wise to him. New York City Police detectives working for the District Attorney’s Office planted a bug in his office to listen in on his dealings with mobsters. The D.A. also wiretapped the phone in the married and philandering Wood’s bachelor apartment.

Mob investors

The racketeers Wood assembled included Alo, the so-called “gentleman gangster” who not only was Wood’s close friend, he was best man at Wood’s wedding. Alo had been close with Mob financier Meyer Lansky since Prohibition. He worked illegal casinos with Lansky in Florida in the 1940s, managed casinos with him in Havana, and was one of the silent partners with Moe Dalitz in Wilbur Clark’s Desert Inn in Las Vegas. After the Castro revolution drove the gangsters out of Havana in 1959, Alo was in the hunt for a new racket.

Others in Wood’s circle for Scopitone included Alo’s friend and Genovese capo Joseph “Joe the Wop” Cataldo; jukebox racketeer Francis “The Irishman” Breheny; Aaron Weisberg, an investor in the Mob-connected Sands Hotel in Las Vegas; and a New Jersey jukebox maker associated with the Genovese family, Abe Green. New York Mob boss Frank Costello also frequented Wood’s office. Green was to distribute the machines. Genovese man Catena, an underling of aging Mob boss Charles Luciano (who would die a year later in Italy), received the right to refuse any new investors.

The first Scopitones in America, installed in “high-class” cocktail lounges, nightclubs, hotels, motels and restaurants, at first served as a novelty, exhibiting films of French pop singers unfamiliar outside Europe. The foreign-made machines offered a choice of 36 selections for a quarter per play. But to have a viable future, the machines needed American content. Wood’s gambit was to rake a 10 percent production fee off of each film placed in the machines. Plans were made for new, upgraded Scopitones manufactured in the United States and to produce films for them featuring U.S. recording artists.

Then, in 1963, Alvin Malnik, a Miami attorney and a buddy of Meyer Lansky, inquired about buying the American rights to Scopitone Inc., with partners Abe Green and three other New York investors. Malnik told The New York Times that through a “broker,” he contacted Tele-A-Sign president A.A. Steiger about building the machines. Malik, Green and Green’s partners agreed to purchase the shares in Scopitone and distribute them evenly. But on July 29, 1964, with power of attorney granted by the partners, Malik transferred an 80 percent interest in Scopitone to the Genovese-controlled Tele-A-Sign for stock worth $3.5 million. Instead of distributing the shares equally among the partners, Malik kept for himself about 90 percent of the shares he acquired in Tele-A-Sign and sought the remaining 20 percent of Scopitone. Malnik claimed he deserved it for doing most of the work on the deal. But he in fact had helped Alo and Catena pull a fast one. Green and his investors, left with as little as 10 percent of Tele-A-Sign, were, of course, furious. They demanded a meeting with threats of litigation.

In the meantime, Malnik worked with William Morris and Tele-A-Sign’s Steiger to find a producer of American films for Scopitone, as Alo and Catena stayed on the sidelines. In August 1964, days after his undisclosed Tele-A-Sign stock coup, Malnik said of Scopitone in the Los Angeles Times: “It’s not a competitor to the jukebox. It’s a new entertainment medium in its own right.”

Enter ‘Jimmy Blue Eyes’

When Green and partners met at New York’s Warwick Hotel in late 1964, “Jimmy Blue Eyes” Alo, not Malnik or Steiger, was there to represent Tele-A-Sign. Alo’s notorious status must have worn down the unhappy partners. In spring of 1965, Green’s group dropped its demand for 35 percent of Tele-A-Sign and accepted Alo’s offer of 25 percent. Alo and the Genovese family had won. But what they had done was no secret. Attorney General Robert Kennedy and the U.S. Justice Department knew all about the Malnik transaction from the start in 1964. The federal government launched a secret grand jury investigation into Malnik, Alo, Scopitone and Tele-A-Sign, and the Securities and Exchange Commission started its own probe.

Tel-A-Sign was a publically traded manufacturer of large illuminated plastic signs for service stations, markets and other businesses when the Genovese family essentially took it over in 1964 as the exclusive maker of American-model Scopitones. The firm began delivering 500 of the new machines from its Chicago factory each month starting in January 1965, with a goal, announced in newspapers and trade publications, of producing 10,000 of the devices. The machines, distributed nationwide, carried a hefty price tag at the time — $3,500 each and another $720 for the rights for the 36 films running inside. The films were changed weekly for a $60 monthly fee. Steiger told the media they only made money from the sales of the machines, not the quarter-dollar coins placed in them. Machine owners were making good money for the mid-’60s, from $75 to $375 a week. Scopitone was not the only brand of sound film jukeboxes, but it was the best selling by far. A Scopitone was even reportedly installed at the White House.

Debbie Reynolds and her Harmon-EE company, after signing a production deal with Tele-A-Sign, with Briskin as film director, churned out four new 16mm sound and color films per month in early 1965. They knew what they were doing. The singing stars and Harmon-EE’s stock group of singers and dancers rehearsed (at the sound stage Reynolds owned in Hollywood) for a day and performed before the camera the next, at a cost of $6,000 to $11,000 per film. The early films were directed toward adults (specifically men) in cocktail lounges. Briskin at first decided not to make song films catering to the dominate young pop scene, which changed quickly from hit to hit and made it difficult to keep up. But while producing the first batch of 26 films, Briskin did begin to shift toward “the youth market,” highlighting the new sexual boundaries of the 1960s. Many of the newer films had sexually suggestive themes and showed women dancing in bikinis.

Scopitone stars

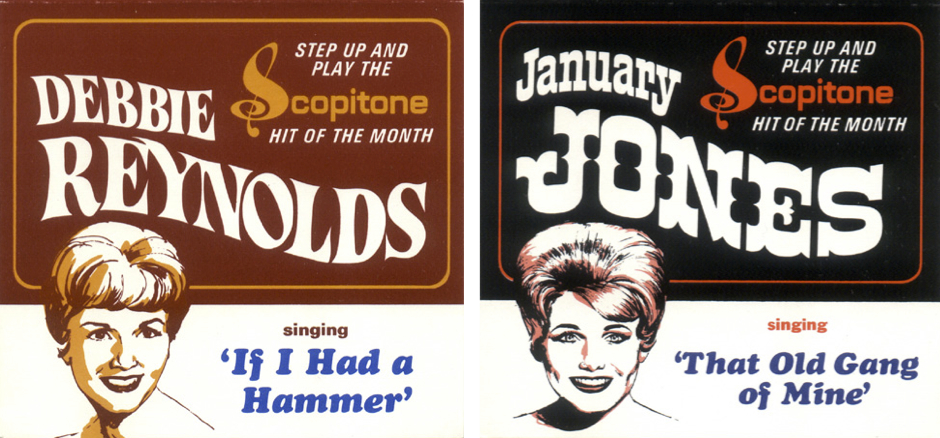

Singers Barbara McNair, Della Reese, Jane Morgan and Reynolds herself were among the first Scopitone stars, followed by Kay Starr, Joi Lansing, Frankie Avalon, Bobby Vee and James Darren. A racy music film of bikini-clad blond singer January Jones, a former Las Vegas cocktail waitress, catapulted her to stardom as the “Scopitone Queen.” In one late 1965 film, rock ’n’ roll singer Stacey Adams performed “Pussycat A Go-Go” as women in bikinis gyrated poolside at a Las Vegas hotel. Another featured Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walking.” The single was a No. 1 hit after its release in February 1966. The Scopitone film shows the sultry Sinatra backed by dancers cavorting in short-short mini-skirts. As for Reynolds, she and other Scopitone singers of her generation stuck to more conventional tunes. In one of her films, she belted out “We’ll Sing in the Sunshine,” a happy, middle-of-the-road song shot at a ranch in California, but even that film featured dancing woman hiking up their long skirts.

Briskin told the Los Angeles Times in August 1965: “We start with a popular record done by the artist and synchronize it to a 35mm silent movie of the performer and suitable backing. The 35mm film is then reduced to 16mm. In the back of the machines the film with the accompanying soundtrack is projected to a mirror, then to the screen. Reels rewind automatically after playing. Technicolor does the printing.”

Briskin said his stable of singers was doing well performing the “new music,” rock ’n’ roll, for the first time. “Femme artists who have been appearing professionally fully clothed come over sensationally on Scopitone in bikinis,” he added.

Scopitones were a hit for the most part among Americans from 1965 to 1966, as business owners reported steady profits. Lounges and clubs with the machines advertised them widely in newspapers to lure customers. As early as the summer of 1965, the machines were operating in 1,300 locations.

Federal probe

But in December of that year, a federal grand jury convened to investigate Malnik and Alo in the Tele-A-Sign stock deal. Alo was called before the SEC to testify about his alleged hidden ownership in Tele-A-Sign. He pleaded memory lapses to 134 questions about Tele-A-Sign, Scopitone and the New York meetings. Meantime, sources leaked news of the grand jury probe to the Wall Street Journal in April 1966. Just as Scopitone’s business was rising, distributors and stockholders jumped ship amid the revelations of Mob involvement. The machine company declined and finally folded in 1969, and with it, the era of the audio-visual jukebox. Both Malnik and Alo were indicted based on the SEC investigation. But federal prosecutors discovered the FBI had illegally wiretapped Malnik, a lawyer, back in 1963 and dropped his charges in 1971. Alo wasn’t so lucky. In 1970, he was convicted of obstructing justice and giving false and evasive answers to the SEC, sentenced to five years in federal prison and released after serving three.

By all accounts, Debbie Reynolds was an innocent victim, something of a pattern throughout her adult life. There was the embarrassing publicity about the Mob connection. But Scopitone turned out to be yet another business venture from which she was abused financially by men closest to her. The film production deal ground to a halt, and she lost an undisclosed amount of money. Afterward, she said little about Scopitone over the years. Of her three autobiographical books, she mentions Scopitone only in 1988’s Debbie: My Life, and then in passing, twice, with hints of bitterness.

Reynolds, who was married to shoe store chain magnate Harry Karl during the Scopitone period, wrote of Briskin’s actions as her business manager. “Anything I earned automatically went to Irving Briskin, who managed it with Harry.”

She ended up losing about $10 million between Briskin’s questionable investments (including a hospital in Santa Monica) and Karl, who squandered and gambled away millions. In 1972, she sued Briskin in Los Angeles for $350,000 for undervaluing shares of stock she sold him and debts he owed her. She settled out of court for $300,000 – in government bonds.

“Irving put some of my money into a video machine called Scopitone that was twenty-five years ahead of its time,” she wrote. “The Scopitone machine was so far ahead of its time, no one bought it.”

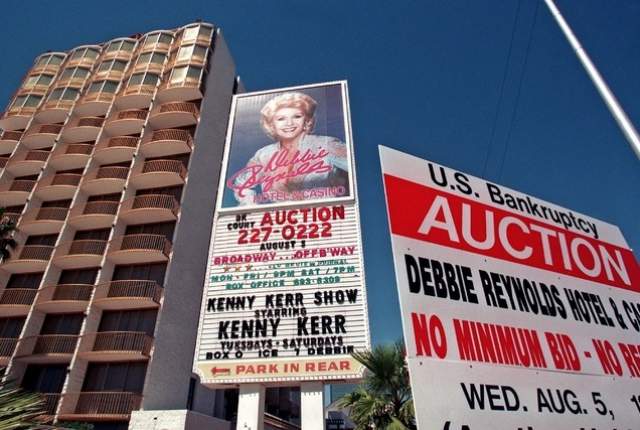

Las Vegas drama

Another disappointing business venture was a small hotel-casino in Las Vegas. Reynolds and third husband Richard Hamlett bought the Paddlewheel hotel-casino on Convention Center Drive, just off the Strip, in 1992. It reopened a year later as Debbie Reynolds’ Hollywood Hotel, and included a museum featuring her collection of movie memorabilia. The hotel struggled, and Reynolds and the hotel filed for bankruptcy in 1997. She sold the hotel in 1999. It remained open under other names until 2015, when it was demolished.

Reynolds’ experience with the Las Vegas hotel involved yet another series of outrages from a spouse. In June 1993, as she would recount in her 2013 book Unsinkable, she struggled to open the hotel and its theater, borrowing money and making last-minute changes. The Building and Safety Department informed them of complaints they received about construction problems at the hotel – complaints from Hamlett himself. On opening night, while she was in mid-song in her new theater, she watched Hamlett get up and walk out. Unbeknownst to Reynolds, Hamlett had bet her concrete contractor $10,000 that she would not open the hotel on time, and had to pay up.

The worst part came soon afterward, while the couple was in Reynolds’ condo on the 12th floor of the Regency Towers complex in Las Vegas. Hamlett, she wrote, tried to draw her over onto the condo’s tiny balcony for a talk. “Why did he seem so intent on getting me out to the balcony, which is only about three feet wide — not enough room to have a friendly conversation? Was he thinking about my million-dollar life insurance policy? … I could practically see the dollar signs floating above his head. I was sure he was going to toss me off the balcony. One shove and all his troubles would be over.”

Reynolds wrote that she excused herself to go to the bathroom, then climbed onto a shelf in a closet behind some suitcases and remained there to hide until Hamlett left. Then she called her building’s security and instructed that Hamlett not be permitted to enter or park at the building ever again.

When she asked Hamlett for a divorce the next day, she said he told her he had been seeing a mistress, and added: “I’m in it for the money. I’m not leaving. You’ll never get rid of me. I control everything. It’s all in my name. You’re just a figurehead. You’re nothing. And I don’t love you.”

After watching Hamlett walk away from her son’s Las Vegas home, Reynolds was resigned to having been taken for a ride again by a husband. “Although I never wanted to see him again, I knew it couldn’t be avoided – we’d see each other in court, if no place else. I’d been in this movie before.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org