The Gangsters at the Heart of Russia’s Story

Expert explains organized crime’s origins and place in former Soviet Union

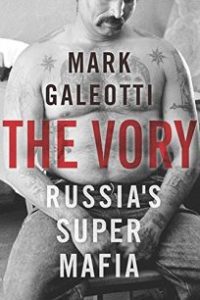

Russian gangsters are often fascinated by the Cosa Nostra, and one once asked me, can one write the history of America without its gangsters? Probably, for all that its wiseguys, godfathers and gangbangers have been powerful from time to time. But as I discovered researching and writing my book The Vory: Russia’s Super Mafia, Russia’s mobsters have played a much more direct, sometimes even pivotal role in that country’s evolution from a backwards giant in the 19th century to today’s geopolitical antagonist.

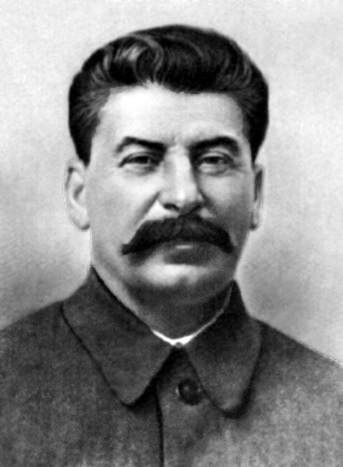

In the early 20th century, the Bolshevik revolutionaries funded their underground printing presses with the proceeds of bank robberies and even pirate raids on the Black Sea, some masterminded by one Joseph Dzhugashvili, later to be better known as Stalin. The Bolshevik revolution of 1917 might have gone in a very different direction had one particular Moscow gangster, known as “Sasha Purses,” had better hearing and paid more attention to the news. One night, he flagged down Bolshevik leader Lenin, but misheard his name as “Levin” and didn’t realize quite whom he was holding at gunpoint until it was too late.

When Stalin took power, a central element of his brutal rule was the network of Gulag labor camps. Millions of innocents toiled as virtual slaves, and Stalin turned to the professional criminals, the so-called vory, to be the foremen and guards who kept them in line.

After his death, as the Soviet system slid into shabby decay, the vory survived behind the scenes as the connective tissue between corrupt Communist Party officials and the black marketeers who could get them rare Western luxuries. When the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of 1991, though, they were able to burst out of the shadows. They cornered markets left by the retreat of the planned economy. They used their dirty money and dirtier connections to snap up businesses and real estate being hurriedly privatized. They used the guns and muscle that were now so available to fight out turf wars in the streets.

This couldn’t last, and when Vladimir Putin ascended to the Russian presidency in 2000, those wild days soon came to an end. The new tsar in effect offered them a deal: They could carry on their criminality so long as they did nothing to challenge or threaten the state. A generation of new rich gangster-businessmen who had made millions exploiting the chaos of the 1990s quite liked the idea of regularizing their place in society, not so much going legitimate as reaching an understanding with the Kremlin. Besides, Putin made it clear that the state was the biggest gang in town, and no one could challenge it with impunity.

Every now and then, after all, Putin likes to remind the godfathers of this. Back in the 1990s, for example, when he was deputy mayor of St. Petersburg, Russia’s second city, he had dealt with the Tambovskaya gang, and its boss, Vladimir Kumarin (also known as Barsukov). They did so well, not least because Putin gave their Petersburg Fuel Company the city’s gasoline monopoly, that Kumarin came to be known as the “Night Governor” – by day, it was the officials who ran the city, but by night it was Tambovskaya.

Once local boy Putin had become president, though, this became something of a problem. The Kremlin felt Kumarin had a bit too high of a profile, was a little too embarrassing for a president who liked to present himself as Mr. Clean.

Crunch time came when Kumarin defied the Kremlin and tried to intimidate a businessman close to Putin and the local governor. On August 24, 2007, about 300 elite police commandos from Moscow stormed his home, and he was arrested and airlifted to Moscow. The official reason for such measures was fear he would be tipped off by informants in the St. Petersburg police, but it was also deliberate overkill to make a point – that even the country’s most powerful kingpins are nothing before the power of the state.

Some people call Russia a “Mafia state,” but that implies the gangsters are in charge, or that the Kremlin runs the mob. Neither is quite true. Rather, today’s Russia is one in which organized crime is not being beaten, but in a way it has been tamed. The gangsters are ruthless, fearsome, often highly sophisticated. They employ Spetsnaz special forces veterans as assassins, the best computer hackers in the business, and shrewd money managers to launder their cash. But at the same time, they – like everyone in Russia with something to lose – know they survive at Putin’s pleasure. And sometimes the boss expects favors.

To give the last word to that vor who asked me about America, he kept asking “but who runs the Mafia there? The CIA, the president?” When I explained that there really was no such “manager,” just the constant struggle between underworld and law enforcement, and one gang and another, he seemed horrified. “But that’s just anarchy!” Maybe so, but better that than a nationalized mob.

Professor Mark Galeotti is senior research fellow at the Institute of International Relations Prague, a member of the Mob Museum’s Advisory Council, and author of the new book The Vory: Russia’s Super Mafia (Yale).

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org