Elizebeth Friedman: The rumrunner’s worst nightmare

Cryptologist cracked coded radio transmissions to bust liquor smugglers

In the waning weeks of Prohibition in 1933, Elizebeth Friedman, chief cryptologist for the U.S. Treasury Department, was called as an expert witness in the criminal trial of master international rumrunner Bert Morrison in New Orleans. Morrison sold and shipped illegal liquor along the entire Gulf and Pacific coasts, as far south as Belize and British Honduras, for the Consolidated Exporters Corporation of Vancouver, Canada.

Morrison was on trial with his henchmen who had transferred millions of dollars’ worth of alcohol in small boats at prearranged sites and shipped the illicit cargo on trucks through New Orleans. To communicate the whereabouts of the shipments of their barrels and boxes of liquor, Morrison’s group broadcast code words, or ciphers, from a series of radio stations.

Hundreds of messages from Morrison’s rumrunners were received by the U.S. Coast Guard and decoded by Friedman’s cryptology unit in Washington, D.C. The case against the Canadian racketeer was considered all important for federal prosecutors, who had spent a half-million dollars over two years in preparation. Overseeing the prosecution in Morrison case was Colonel Amos W. Woodcock, the well-known former director of prohibition for the federal government.

While in court, Friedman used a blackboard to explain to the jury how cryptologists translated codes into plain language. She read a sample message, referring to a brand of whiskey: “Out of Old Colonel in Pints.” She showed how the three “o” and “l” letters in “Colonel” had identical cipher code letters. From the cipher’s letters for “Colonel” she could figure out the letter the racketeers chose for “e,” the most frequently occurring letter in English, based on other brand names of liquor they mentioned in other messages. The “o” and “l” letters in “alcohol,” she said, had the same cipher letters as “Colonel.” The tactic worked. Morrison and his indicted cohorts were found guilty and sentenced to long stretches in prison.

“If I remember rightly, this was the only case against smugglers where my work was instrumental in bringing the indictments against Bert Morrison and 22 co-defendants,” Friedman later recalled.

Elizebeth Friedman was one side of a master cryptology team with her husband, William Friedman. They were a remarkable pair. William, working for the War Department, broke the cipher used by Japanese diplomats and invented deciphering devices used by the United States during World War II. Elizebeth decoded more than 12,000 messages sent via shortwave radio by rumrunners to help the U.S. Coast Guard confiscate illegal liquor during Prohibition.

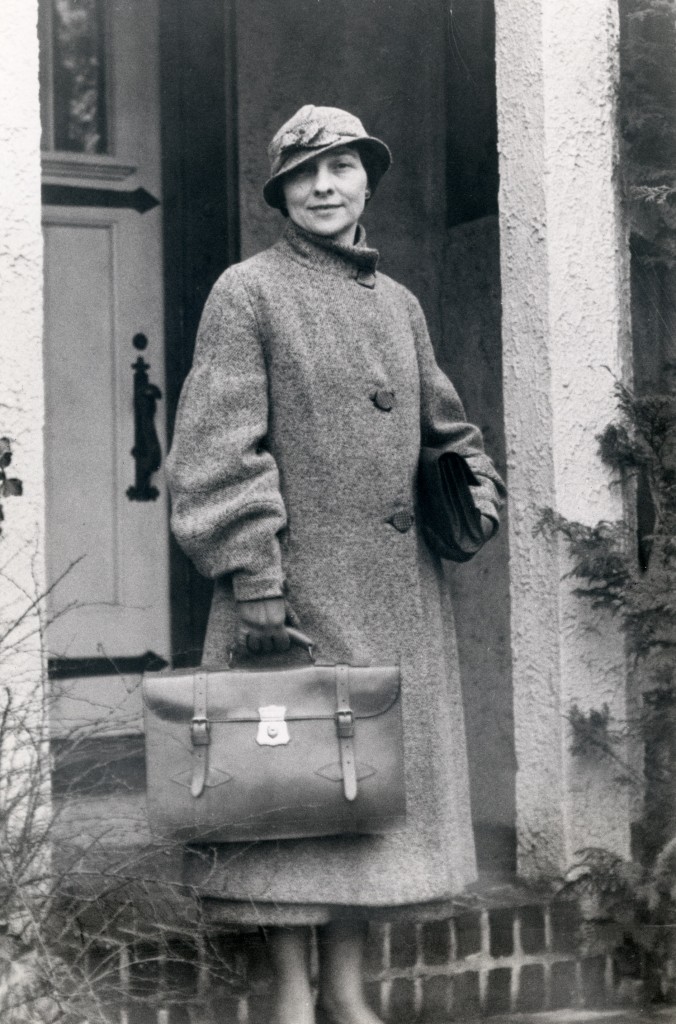

She was born Elizebeth Smith in Huntington, Indiana, on August 26, 1892, the daughter of a Quaker, John Smith, and his wife, Sopha Strock Smith. She attended Hillsdale College in Michigan, studied German, Latin and Greek, and graduated with a degree in English in 1915. She arrived a year later at the Newberry Library in Chicago looking for a job. A librarian offered to contact Colonel George Fabyan, the wealthy owner of, Riverbank Laboratories, the nation’s first private research facility, located on a 500-acre estate in Geneva, Illinois. Fabyan offered Elizebeth a job on the phone and took her to the estate. Among Fabyan’s interests was showing that Francis Bacon used ciphers to prove he was the actual writer of William Shakespeare’s plays and poems. He decided to bring on Elizebeth as an apprentice on the project.

On her first day at the Riverbank estate she met William Friedman, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants. Fabyan hired Friedman to conduct genetics experiments on crops and analyze Shakespeare’s writings through photo enlargements. Elizebeth introduced Friedman to cryptology. They both took to the topic, and to themselves, marrying in 1917. They wrote pamphlets on cryptology and taught courses on the subject for the U.S. Army, which created a Cipher Bureau during World War I. They stayed at the sprawling Riverbank estate studying cryptology for four years before leaving for Washington, D.C., to work in the fledgling profession of cryptology for the U.S. government. By 1921, William was employed as a contract cryptologist by the War Department’s Signal Corps to solve enemy codes and ciphers. Elizebeth also worked as a contract cryptanalyst for the War Department and then for the U.S. Navy from 1922 to 1923.

After moving to a country house in Maryland, they moved again to suburban Chevy Chase outside Washington, where they worked together on a special code commissioned by Edward Beale McLean, the eccentric owner and publisher of the Washington Post. William, at the request of Congress, deciphered the letters of Albert Fall, the Interior secretary under President Warren Harding, that led to Fall’s bribery conviction in the Teapot Dome scandal. Elizebeth gave birth to two children and decided to write a book on the alphabet.

Then, in 1926, Capt. Charles Root, intelligence officer of the U.S. Coast Guard, called Elizebeth to say he wanted her to work with him on developing anti- or counter-intelligence for the Guard to enforce Prohibition laws against rumrunners who were using speed boats to transport illegal liquor. At the time, the Coast Guard was responsible for patrolling America’s 19,000 miles of coastline with a small staff to catch the smugglers. The Coast Guard’s Intelligence squad tapped Friedman for her talents as a cryptanalyst in breaking codes sent by rumrunners using the almost new technology of shortwave radio.

Capt. Root had been working with Harry Anslinger (later head of the U.S. Bureau of Narcotics), who was vice consul in Nassau in the Bahamas, where, as Elizebeth related in a 1966 oral history kept at the George Marshall Foundation in Washington, “the water routes back and forth between the Florida coast and the Bahamas and also Florida to Cuba and back had become one of the highways of liquor smuggling.”

Root and Anslinger came across radio communications on the East Coast sent in the form of ciphers that “were usually not by any organized group but by individuals, ambitious men who aspired perhaps to be the Capones of the profitable game of rum smuggling,” she said.

Elizebeth’s job was to decipher the rumrunners’ secret radio dispatches to let the Coast Guard know what sea routes the runners’ boats were taking so the Guard’s boats could intercept them and confiscate the liquor. At first she worked part time on decoding, including a long telegraph transmission from Havana to the United States in which the sender foolishly used the word “Havana” as a key word, making it much easier to decipher. In 1927, she undertook the cryptologist position on a full-time basis for the Coast Guard and the Bureau of Foreign Control.

“The Coast Guard, being the organization which at sea had to combat rumrunning vessels, had need of something more than just patrol by Coast Guard vessels to operate effectively,” she said. “New York, of course, had been the leading port of entry for the smuggled liquor, but the whole Atlantic coast with its coves and inlets, its chopped waterline, with its many secluded spots where boats might secretly dock and unload, created a problem which defied description.”

In 1928, she transferred to the Treasury Department as special agent to the Customs Investigative Service in the Bureau of Customs and for the next two years focused on decoding ciphers sent by the alcohol-running rings in the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Coast. Nothing seemed to faze Friedman as she decoded ciphered radio messages, from the ordinary to the sophisticated, used by racketeers.

Along with the Coast Guard, two other agencies were monitoring shortwave transmissions by rumrunners – the Alcohol Tax unit and Federal Communications Commission – and inevitably, rivalries ensued among the agencies.

In her high rank with Treasury working against rumrunners, Friedman saw firsthand the uphill battle law enforcement fought to uphold the Volstead Act, the 1919 law that set penalties for violations of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution that prohibited the production, sale and distribution of beverages containing more than 0.5 percent alcohol.

“Few persons in the present day realize anything of the enormity of the situation in the United States while the Volstead Act, which created the so-called Prohibition Era, was in effect,” Freidman said. “The government law enforcement agencies had no more taste for it than the public who loved their drink. But government officials, who with minor exceptions were honest at least, had no choice but to pursue the rigid, torturous paths of attempting to defeat the operations of the criminal gangs.”

“There were not only the far-ranging gangs of operatives under Costello in New York, but there was the Torrio-Capone gang in Chicago,” she recalled. “Capone was said to make from 50 to 100 million dollars a year from beer alone.”

To Friedman, books on the “Roaring ’20s” that emphasized a young generation’s liberation and excesses, such as described in the novel The Beautiful and the Damned by F. Scott Fitzgerald, “were as nothing, in my opinion, among the contributing factors to the decline of uprightness, if not to say morality in the United States, compared to the criminal syndicates which flourished so widely, so boldly, and so freely, because of the existence of the Volstead Act.

“Never had the criminals found such a gushing well of profits,” she said. “Never had the anti-criminal forces encountered such universal tidal waves of law breaking. Conscientious though the vast majority of enforcement agents in the government were, it is true that is was a battle lost from the beginning.”

Most efforts by agents to arrest violators during Prohibition came to nothing, Friedman said. About nine out of 10 of the 50,000 illegal liquor cases bought per year were dismissed by the U.S.

commissioner “to enable the courts to work at all,” she said. “There was also a great deal of time spent in prosecuting prosecutors. When indictments did indeed reach a court and a jury, the juries made acquittals the rule.”

Friedman described Prohibition Era New York as “a sort of international headquarters for Rum Row,” the line of boats holding illegal liquor anchored off shore ready to deliver their cargos. New York Police were making as many as 15,000 Prohibition-related arrests each month, mainly of “small fry” suspects while Mob leader Frank Costello headed the rumrunning operations.

Costello was said to be taking orders from New York’s top booze smuggler, William “Big Bill” Dwyer, while Dwyer served time in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta. Dwyer, a nightclub owner who had run a fleet of speedboats to transport liquor before he was jailed, apparently had a close relationship with Jimmy Walker, New York’s mayor from 1926 to 1932, according to Freidman. Walker’s successor, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, observed in the last year of Prohibition how difficult it was to impose anti-liquor laws there.

“(La Guardia) made a statement that there were 250,000 speakeasies in New York City alone,” Friedman said. “La Guardia estimated that it would take 250,000 policemen to enforce the law in New York City and that it would probably take another 200,000 to keep police in line.”

“The liquor, of course, which came in during the operations of such persons as Frank Costello’s gang plus innumerable individual operators, was gobbled up with great eagerness by the dispensers of alcoholic drink and cut usually about five times before reaching the consumer,” she said. “However, the thirsty public drank the result and no questions asked.”

In the late 1920s, Friedman was called by federal prosecutors to testify in criminal cases about the radio-transmitted codes she broke in rumrunning cases in the Gulf of Mexico, including several in Galveston and Houston, Texas, and New Orleans, and along the West Coast.

“By early 1930, smuggling of liquor had become a gigantic problem,” she said. “The Treasury Department came to believe that a cryptologic unit should be formed and that young people with the proper qualifications should be trained in this mental battle against the underworld of smuggling.”

Thanks to praise she received from federal officials, and the wide attention she drew in the news media, Friedman was appointed to head the new unit of cryptologists. She located the unit in the Coast Guard’s offices in Washington, the best place to receive wireless transmissions transcribed by the Guard’s staff. She hired several young men with high scores on federal Civil Service science tests and trained each one in cryptanalysis, thus expanding the effort against smugglers.

“Many times I’ve been asked as to how my authority, that is the direction and superior status of a woman as instructor, teacher, mentor, and slave driver, even to commissioned and non-commissioned officers, by these men was accepted,” she said. “I must declare with all truth that with one exception, all of the men young or older who have worked for me and under me and with me, have been true colleagues and have never been obstructionists in any way.”

After Prohibition ended in late 1933, Friedman still had to help Treasury deal with the antics of rumrunners, or what she labeled as “the backwash” of the forgone period.

“With such vast amounts of money and large organizations as had been operating in the smuggling era, all activities could not cease and it was physically impossible for the smugglers to wipe out and cast into oblivion the results of their past operations,” she said. “Consequently, cases still arose for a long time thereafter, and although only the most important and those with the most far-reaching implications reached the courts, there was still much action to be taken.”

During the 1930s, Friedman trained U.S. Coast Guard officers in cryptology. She used her skills in analyzing radio messages to solve a dispute between Canada and the United States over the ownership of a ship, the “I’m Alone,” sunk by the Coast Guard (the Americans won the case). She deciphered a code written in Mandarin Chinese, even though she did not speak Chinese, to crack an opium-smuggling case for the Canadian government. In the early 1940s, after the start of World War II, Elizebeth famously deciphered coded letters sent by Velvalee Dickenson, a spy for the Japanese, leading to Dickenson’s conviction. In 1957, Elizebeth and William co-wrote a book proving there were no ciphers hidden in the writings of Shakespeare.

Elizebeth died at the age of 88 in Plainfield, New Jersey, on October 31, 1980. In 1999, she was inducted into the National Security Agency’s Cryptologic Hall of Honor as “a pioneer in code breaking.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org