Eighty-five years ago this week, Lucky Luciano convicted of pandering

Prosecutor Thomas Dewey went all out to take down New York Mafia boss

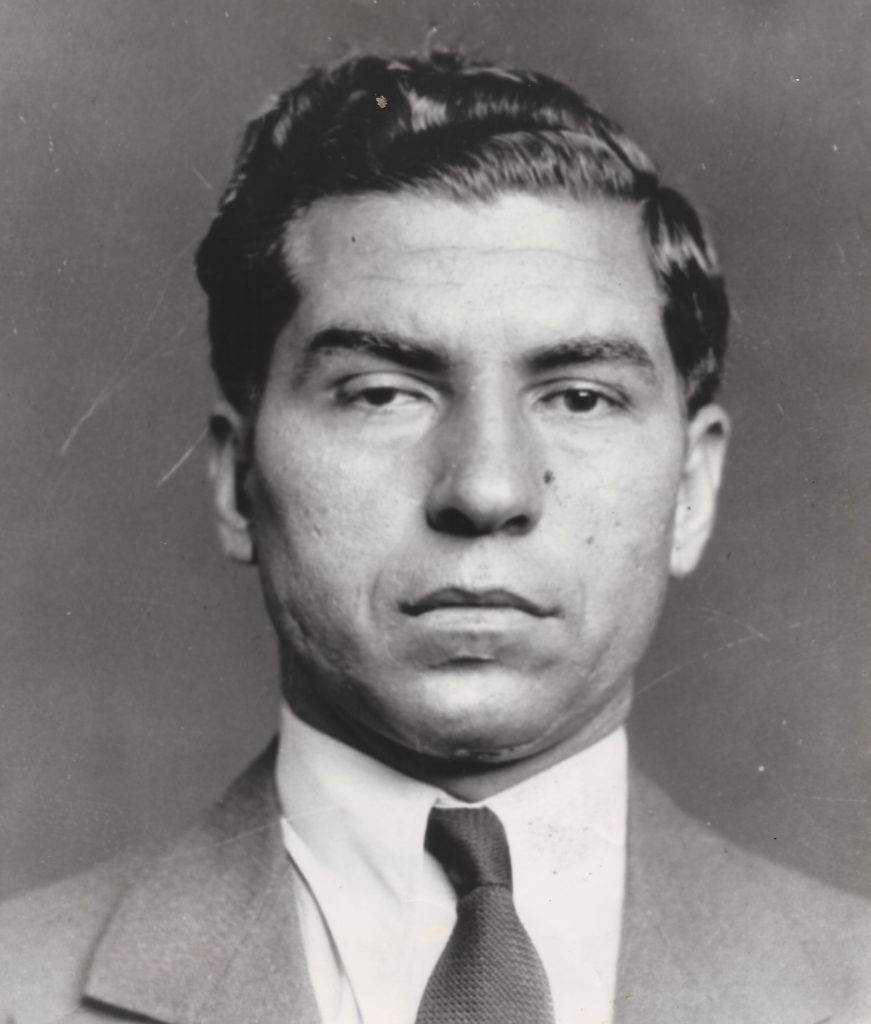

A few years after the fall of Chicago’s Al Capone in 1931, a new recognizable face of organized crime emerged from the streets of New York to decorate national headlines. Charles “Lucky” Luciano took the throne as Public Enemy No. 1, the purported lord of vice in the Big Apple and beyond. And just as the law unrelentingly pursued Scarface, it was hell-bent on putting Luciano behind bars. This time, tax evasion would not be the crime that sealed the kingpin’s fate. New York’s ambitious special prosecutor, Thomas Dewey, opted for an unconventional, yet almost guaranteed slam dunk charge. Dewey’s plan worked, and, 85 years ago this week, Luciano earned international infamy as the pimp of all pimps.

The plan to get Luciano

It was not Dewey’s idea, despite him getting most of the credit and fanfare at the time. Rather, it came from an assistant prosecutor named Eunice Carter. In order to cast an unshakeable aura upon their target, they would accuse Luciano of vices so abhorrent that both the court and the court of public opinion would almost certainly deem them unforgivable sins. Luciano, the prosecution team alleged, was the primary mastermind and beneficiary of a nationally syndicated sex trafficking racket, what was then commonly called “white slavery.” The approach built from a belief that Luciano’s Mob evolved from extorting independent prostitutes and brothels to taking them over outright — thus controlling every element of the estimated $12 million-per-year underworld business. A grand jury agreed, delivering a whopping 90 indictments (later reduced to 62) against Luciano and several others. The recent passage of the Joinder Law allowed the prosecution to bring multiple defendants under one indictment, so Dewey’s team began hauling in various characters.

Word began to spread that prostitutes, madams and associates were cooperating with prosecutors, and, by the early spring of 1936, Luciano got tipped off. In response, he and his then-girlfriend Gay Orlova, a Broadway dancer, skipped town and found refuge in Mob-friendly Hot Springs Village, Arkansas. It should be noted that Luciano was never officially “wanted” in terms of fugitive status, nor did law enforcement agencies ever circulate wanted posters or fliers (if you see such things for sale, they’re fake).

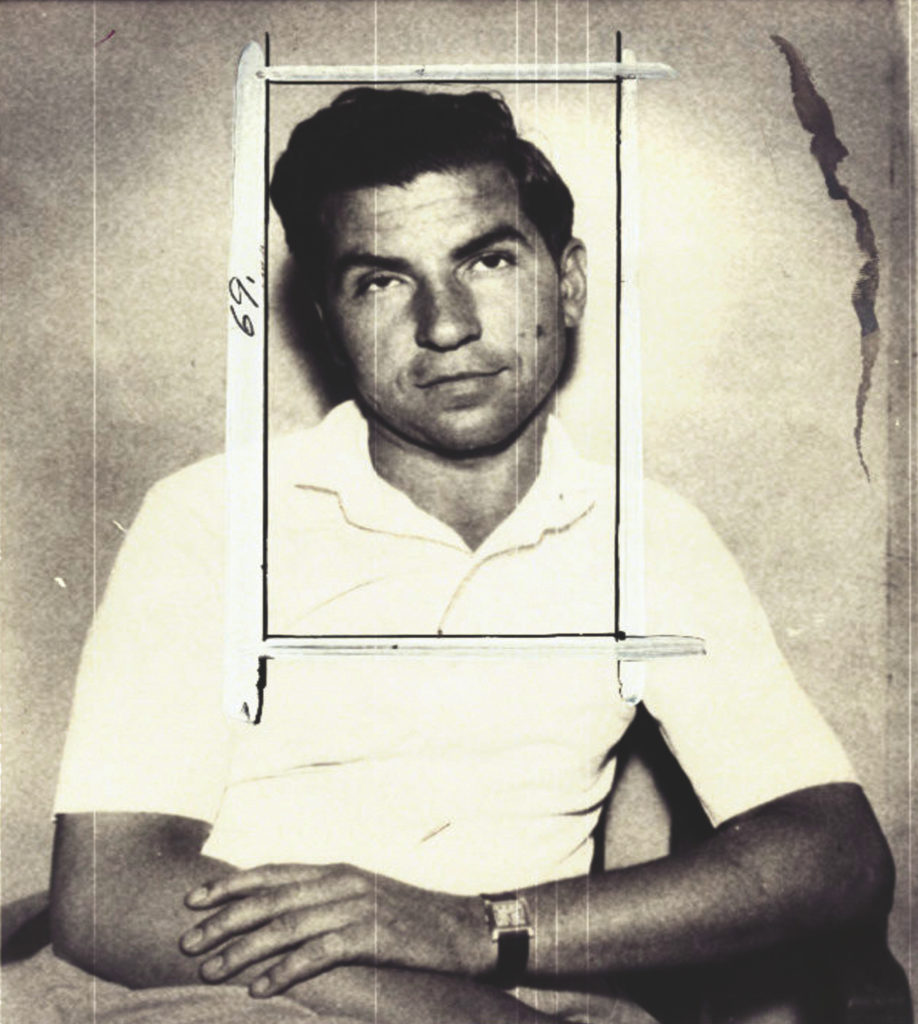

Dewey’s team knew where to find Luciano. Agents from New York came to collect him in Hot Springs in early April 1936. Lucky was held by authorities in Hot Springs while his lawyers fought to avoid, or at the very least, delay the extradition. They managed to hold Dewey’s troupe at bay until April 18, when Luciano’s luck ran out and he was whisked back to New York on a train, under heavy police guard. Police grilled the gang boss upon his arrival.

Captain Mooney: ”What’s your business?”

Luciano: ”Horse-racing.”

Mooney: “Are you involved in the white slave trade?”

Luciano: “Never heard of it.”

After questioning, Luciano’s bail was set at $350,000, and he was placed in a cell to await arraignment.

Trial and error

The trial against Luciano and his co-defendants began on May 13. Dewey’s case foundered during the first week, essentially for lack of any substantial connection between Luciano and the prostitution ring. The general assertion was that Luciano was so well insulated that none of the prostitutes would have even known him. “Nobody was allowed to mention his name,” Dewey asserted.

That all changed the following week when prostitute Florence “Cokey Flo” Brown took the stand and claimed she overheard Luciano and other so-called “bookers” of the ring. She recounted a specific conversation in which Luciano allegedly proclaimed a desire to unify whorehouses into a chain, similar to supermarkets. State witness after witness took the stand, each offering his or her perspective and/or personal relationship to the ring’s inner workings.

Luciano’s defense team wanted to put Gay Orlova on the stand, a move the mobster adamantly refused, telling reporters, “I don’t want her mixed up in this case.” Dewey also considered putting Orlova on the stand – that is, until he met her. The star of Earl Carroll’s Vanities revue appeared in Dewey’s office adorned in diamonds and fur, then gushed praise at the mere mention of her lover’s name. “Oh, I’m infatuated with Lucky,” she said. “He’s so sinister.” Prosecutors realized Orlova would not be a good state witness.

Bucking attorney Morton Levy’s advice, Luciano decided to take the witness stand. Dewey’s cross examination was unrelenting. Everything from taxes to dope to phone calls with ringleaders, almost nothing was off limits in Dewey’s cache of questioning. In his closing arguments, Dewey admitted he couldn’t “prove that Lucania directly placed girls in houses,” but reasoned the crime boss “graduated from that.” He went on to characterize Luciano as “the greatest living gangster in America” and posed the ultimate question to the jury: “Isn’t it time the boss was convicted?”

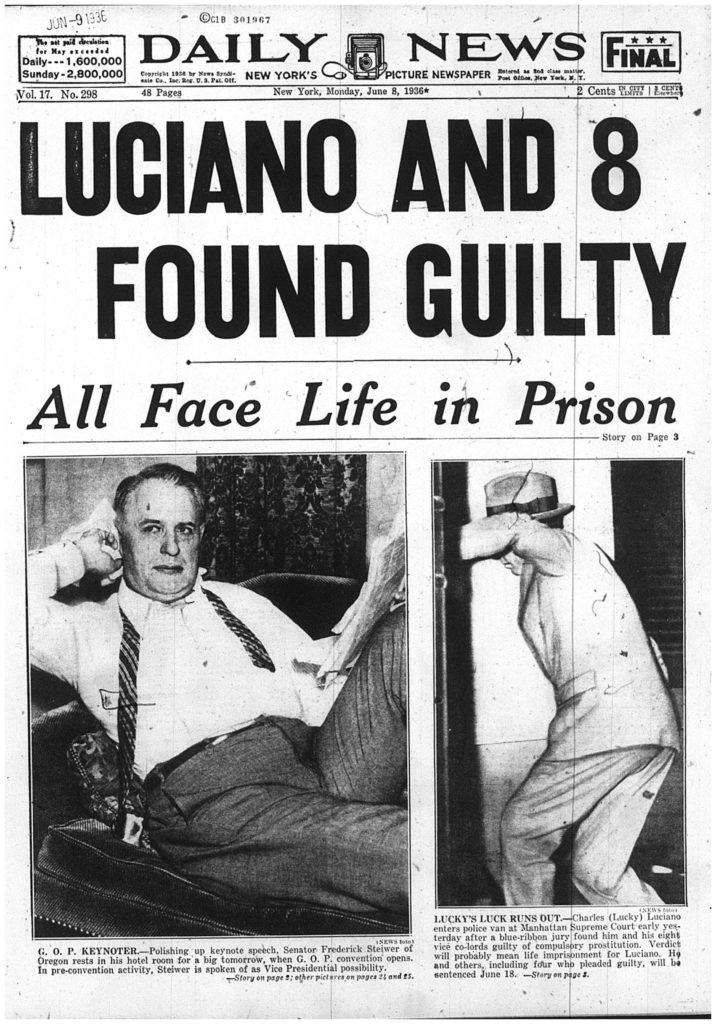

On June 9, the jury found Luciano and nine co-defendants guilty of 62 charges. Judge Philip J. McCook instructed the jury to deliberate on sentencing. They returned on June 18, wherein McCook then addressed each of the defendants with equal, if not more vicious admonishment than prosecutor Dewey had during trial. For example, as he declared the sentences for each defendant, McCook described David Betillo as “an unprincipled and aggressive egoist” and Jack Ellenstein (aka Jack Eller) as “flabby of body and soul.” Luciano, of course, took the brunt of the insults. “Charles Lucania, the crimes of which you stand convicted make you responsible for every foul or cruel deed of all these other defendants. There is no excuse for you,”McCook said.

Luciano also received the harshest sentence. On the opposite end, three of the defendants received considerably light sentences for either pleading guilty at the start or for cooperating with the state. Here are the sentences for each of the 10 defendants.

- Charles Luciana (as his name was spelled in the court records), 30 to 50 years.

- Dave Betillo, 25 to 40 years

- Jimmy Frederico, 25 years

- Ralph Ligouri, 7 to 15 years

- Abbie Wahrman, 15 to 30 years

- Thomas Pennochio, 25 years

- Jack Ellenstein, 4 to 8 years

- Pete Harris, 2 to 4 years

- Dave Marcus, 3 to 6 years

- Al Weiner, 2 to 4 years

Fair trial?

Did Luciano get a fair trial, or did the prosecutor have ulterior motives? It’s a question that remains a subject of considerable debate. Ellen Poulsen, author of The Case Against Lucky Luciano: New York’s Most Sensational Vice Trial, says Dewey certainly fit the “sterling American” image, but was ultimately “unethical” in terms of how the Luciano trial unfolded. “Nobody was an actual eyewitness,” she says. “Everything those women said about Luciano was hearsay.” Poulsen tells us Dewey’s methodic placement of Luciano among defendants that, in reality, the gang boss likely would never have known or associated with was a tactic “to diminish Luciano’s character,” a strategy to make Luciano look equal to the perceived common thug. As for the jury’s ease in convicting, Poulsen believes this is partially a result of bias on the bench. “An ethical lapse on the part of the judge for not explaining to the jury that the testimony was hearsay,” she says, adding, “but also Dewey’s case was carried out in a convincing, sympathetic way, with emphasis on victims, but still hearsay evidence.”

After the trial, some witnesses recanted, and stories emerged accusing the prosecution of providing “incentives” to some of the witnesses (Cokey Flo and Mildred Balitzer in particular), and the prosecution’s true motive was even called into question during the trial’s final days. One of the most vocally opposed to the whole affair was Anna Kross, the first woman judge to serve in New York Magistrate court. A passionate advocate for social justice, Kross’s idealism, however, proved too avant-garde for those in power, especially New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and special prosecutor Dewey, both of whom largely dismissed her commentary. To be clear, Judge Kross was not involved in the Luciano trial, nor did she think Lucky was any sort of saint. However, the Luciano situation served as the impetus to publicly vocalize her dissatisfaction with an unbalanced system:

“Clinical and hospital facilities for the treatment of venereal diseases are most inadequate; our institutions for the care of the feeble-minded and psychotic are overcrowded. There aren’t public funds enough for these things, we are told. But there seems to be plenty of money available at all times for politically inspired crusades and investigations that prove nothing and get nowhere.” As for the conviction of Luciano, Judge Kross called it a “Roman Holiday,” adding that such exploits were convictions of a few ‘“scapegoats.”

After the fall

Luciano’s attorney asked the court for time so that his client could get business affairs in order. The request was denied. Further, the judge and prosecutor agreed that all the defendants be quickly transferred to prison, and ideally split up. Corrections Commissioner Edward Mulrooney visited Sing Sing on June 29 to take a look at the convicted mobsters. To his dismay, Mulrooney observed inmate number 92166, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, presiding over a prison yard entourage. “They were out in the exercise court, stripped to the waist and bathing in the sun,” Mulrooney said. “Luciano was walking around, waving his arms, apparently laying down the law to the rest of the boys.” The commissioner immediately decided to separate most of the defendants. Pennochio and Ellenstein went to Attica. Luciano, Ligouri and Betillo ended up in Clinton Prison. Abe Wahrman was shipped to Auburn. The remaining members, all on relatively short prison terms, were not an immediate concern.

Dewey, meanwhile, shot up the political ladder, reaching the governor’s office. Ironically, that is where he would sign a commutation order, under still-mysterious circumstances, for the man he put away less than 10 years earlier.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Lucky Luciano: Mysterious Tales of a Gangland Legend and Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org