Did the Chicago Outfit elect John F. Kennedy president?

Long-held claims of Mob influence do not hold up to scrutiny

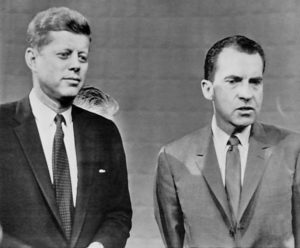

A number of authors assert, based on claims by individuals who were linked in one way or another to organized crime in Chicago, that the Chicago Mob — usually referred to as the “Outfit” — was responsible for John F. Kennedy’s election as president in 1960. It is alleged that John Kennedy’s father, Joseph, met with Outfit boss Sam Giancana before the election and struck a deal. If Giancana made sure that Kennedy was elected, Kennedy in return would “lay off” organized crime when he was president. Supposedly the Outfit kept its end of the bargain, but it was double crossed by the Kennedys, who increased federal pressure on the Outfit locally and the Cosa Nostra generally. In several versions of the story, the Outfit retaliated by assassinating John and Robert Kennedy.

These books, and associated television programs and media coverage, have received a great deal of attention. So much that many people now treat it as an established fact that the Outfit elected Kennedy. More recently, these claims are prominent in the blockbuster movie The Irishman directed by Martin Scorsese.

But did this really happen? As I point out initially in my book The Chicago Outfit and analyze in detail in an article titled “Organized Crime and the 1960 Presidential Election” that appeared in the academic journal Public Choice in 2007, there is no convincing evidence to support these claims about the 1960 presidential election.

The Kennedys and the 1960 election

Several authors discuss the role of the Outfit in the 1960 presidential election. The earliest statement, by William Brashler in The Don, is quite mild. He argues that Frank Sinatra, who knew Sam Giancana and John F. Kennedy, approached Giancana and asked for his help in electing Kennedy. However, the Outfit’s efforts were secondary to those of the Chicago Democratic Party political machine, which went all out for an Irish-Catholic strongly supported by Mayor Richard Daley. According to Brashler, “an order from the mob to work for Kennedy only insured a total Chicago effort of the kind that historically had been known to work miracles in the early-morning hours of vote counting.” In other words, the Chicago Democratic Machine delivered on Election Day for John Kennedy, essentially as it always did for its candidates, with the Outfit-controlled wards doing little (if anything) extra. In his autobiography Man Against the Mob, former FBI agent William Roemer provides a similar account of the events surrounding the 1960 election. Roemer, it should be noted, had developed two high-placed informants in the Outfit. He was, therefore, uniquely informed about what happened in that world.

A greatly amplified version of the story appears in the book Double Cross by Sam and Chuck Giancana, the half-nephew and half-brother, respectively, of the Outfit boss, Sam Giancana. According to the Giancanas, Joseph Kennedy, the father of John Kennedy, struck a deal with Sam Giancana before the 1960 election. “I help get Jack elected and, in return, he calls off the heat,” Sam Giancana is reputed to have said. The Giancanas claim the Outfit did everything possible for Kennedy in the wards they controlled. Allegedly, there was massive fraudulent voting, and hoods inside polling places made sure all ballots were cast for Kennedy by breaking the arms and legs of those who did not comply. The Kennedys, however, double crossed Giancana and the Outfit, despite Giancana supposedly meeting with John Kennedy at the White House to remonstrate with him. According to these authors, this caused the Outfit to assassinate both John and Robert Kennedy.

Seymour Hersh, in a chapter of his book The Dark Side of Camelot titled “The Stolen Election,” also maintains the Kennedys struck a deal with the Outfit. Former Chicago lawyer Robert McDonnell claims he helped arrange the meeting between Joseph Kennedy and Sam Giancana in Chicago, which curiously McDonnell saw take place but did not attend. McDonnell asserts the Outfit got out the vote at the ward level in Chicago for Kennedy. Gus Russo, in The Outfit, repeats the stories told by the Giancanas and Hersh, claiming that “scores of Giancana’s ‘vote sluggers’ or ‘vote floaters’ hit the streets to ‘coerce’ the voters.” Russo, summarizing the election events overall, states quite strongly that Outfit chieftain Tony Accardo, the Mob’s political point man Murray Humphreys, and other top Chicago hoodlums met in June 1960 to “decide who would become the next president of the United States.” A recent book by Antoinette Giancana, John Hughes and Thomas Jobe repeats the extreme claims that the Outfit elected Kennedy in 1960.

On the other hand, Len O’Connor, the dean of Chicago’s political commentators, remarks in his book Clout:

“The power of the Daley Machine was evident throughout the city, only the two crime syndicate wards, the First and the Twenty-eighth, delivering a low count, fewer votes for Kennedy in 1960, in fact, than they had delivered for Daley in 1955. The Machine interpreted this disappointing performance as a mild rebuke by the syndicate people who had been mercilessly pounded by the presidential candidate’s brother, Robert [at the McClellan Committee hearings].”

O’Connor discusses how Charlie Weber, the Democratic alderman of the 45th ward, openly opposed the Kennedys, having been influenced by his friend Murray Humphreys to take a dim view of Kennedy’s candidacy. O’Connor was certainly well informed about Chicago politics, counting aldermen such as Weber among his sources, and was a contemporary observer of the 1960 election.

Several of these accounts also discuss voting by labor union members, locally or nationally. For example, in Hersh’s book Robert McDonnell alleges the Outfit pressured various unions (although it is unclear whether he means locally or nationally) to support Kennedy. Murray Humphreys’ second wife, Jeanne, is more specific. She claims the Outfit delivered Teamsters Union votes at the national level. She professes to not only have witnessed Humphreys coordinating this effort, but to have worked alongside him as he directed Teamsters leaders from around the country Russo also alleges that the Outfit, through Murray Humphreys, made sure that union members nationally voted Democratic. Although he quotes Mrs. Humphreys’ Teamsters-focused account, Russo asserts that non-Teamsters union members nationally were influenced to vote for Kennedy and places particular emphasis on four states: Illinois, Michigan, Missouri and Nevada. On the other side of the ledger, O’Connor argues that unions tied to the Outfit were very displeased with Robert Kennedy and the McClellan Committee hearings and therefore John Kennedy.

A closer look at the sources

When closely examined, the claims that appear in the books by the Giancanas, Hersh and Russo are implausible and are based on sources who lack credibility. For example, there is not one word in any of Chicago’s four major daily newspapers about any violence directed at voters in November 1960, much less of a 1920s-style wave of terror around Chicagoland. In fact, legendary crime reporter Ray Brennan, writing the day after the election, described it as “sissified” and “bland” in comparison to the violent primary election of April 6, 1928.

More generally, the Outfit simply did not have the ability to deliver for Kennedy in Chicago in a meaningful way. According to a federal government report, in 1960 the Outfit controlled the (Democratic Party) political machinery in five of the 50 Chicago wards: the 1st, 24th, 25th, 28th and 29th. There were 279 precincts/polling places in those wards. To effectively intimidate voters at a polling place, it would have taken at least four or five hoods. A smaller number would have allowed irate voters to pummel the “intimidators.” With about 300 full members in 1960, and many of these of advanced age, the Outfit would have been able (if the police did not intervene) to coerce voters in essentially only one of these five wards because each ward had between 46 and 63 precincts. On this point, note that when Al Capone’s goons helped elect the Republican slate of candidates in Cicero in 1924, he needed to bring in additional men from Dean O’Banion’s North Side Gang and others. Capone’s Prohibition-era gang, with 500 gunmen at its height, was larger than the Outfit in 1960, while Cicero was quite a bit smaller (about 70,000 inhabitants in 1924) than the five Outfit-controlled Chicago wards (whose total population was more than 300,000 in 1960).

Allegations that the Outfit manipulated the Teamsters or other unions nationally are equally implausible. Individual Cosa Nostra crime families generally controlled local chapters of unions rather than the national union. Therefore, the Outfit was in no position to command Teamsters — or other union officials — from around the entire country to do their bidding. More importantly, Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa hated the Kennedys and publicly endorsed Richard Nixon, which eliminates the possibility this union influenced its members nationally to vote for Kennedy. This probably leads Russo to modify Mrs. Humphreys’ story to one where the Outfit influenced non-Teamsters unions to vote for Kennedy.

It is also hard to believe that Joseph Kennedy met with a notorious mobster who was investigated by a Senate committee his two sons were associated with. If John Kennedy had been linked publicly to Giancana, the damage to his campaign would have been immeasurable. Even a hint of this, leaked to the press by someone involved, would have been damaging. Also, it is hard to imagine how the Outfit, after being attacked by the McClellan Committee, would trust the Kennedys or believe they would not continue on the same course. In fact, Ray Brennan reported in a newspaper article just two days after the election that John Kennedy intended to crack down even harder on organized crime, including the Outfit, as an outgrowth of his activities on the McClellan Committee. And Bobby Kennedy had already labeled organized crime as the greatest danger facing the country in his book The Enemy Within.

The details of McDonnell’s story about the meeting between Joseph Kennedy and Sam Giancana are also not plausible. First, Joseph Kennedy supposedly solicited Chicago Judge William Tuohy, who in turn contacted Bob McDonnell, for help in contacting Sam Giancana. Yet McDonnell admits he did not know Giancana. Tuohy could easily have contacted First Ward Democratic politicians, such as John D’Arco or Pat Marcy, who were close to Giancana, to more effectively arrange a meeting. Second, McDonnell claims Tuohy wanted him present at the actual meeting. Yet as soon as the parties were introduced, Tuohy and McDonnell left the building. If McDonnell’s presence was not required at the meeting itself, why was it necessary that he be there at all?

The credibility of several individuals who make these claims is also questionable. In reality, organized crime operates with a degree of secrecy identical to that used by major intelligence agencies such as the CIA or KGB. Only those who absolutely “need to know” are informed at the time about particular operations. The average soldier (lowest rung, full member) of the Outfit would not have known the information the Giancanas claim to have known, much less Chuck Giancana, who was at best a lowly Mob associate. Moreover, the Giancanas’ book is not taken seriously by well-informed students of the Chicago Outfit. In it the authors claim Sam Giancana was involved in every major event related to organized crime in Chicago that occurred from his adolescent years onward, even though many of their assertions are contrary to the known facts or are unsupported by other evidence.

The same point applies as strongly, if not more strongly, to Jeanne Humphreys. In the completely male world of traditional American organized crime, members do not share information with females, including wives. This is a standard in the Cosa Nostra. Female relatives of gangsters have, in fact, made remarks to this author such as, “I’m a girl. They never told me anything.” Certainly, union leaders would have refused to conduct business with Humphreys if a woman or non-Outfit member were present. In fact, if Humphreys had even suggested to his superiors that his wife attend such meetings — much less that she work with him — they would have concluded he was insane and almost certainly killed him and her as well.

Robert McDonnell is similarly lacking in credibility. A disbarred attorney who was a compulsive drinker and gambler, McDonnell borrowed heavily from loan shark Sam DeStefano, a Mob associate, to support his gambling habit. When he was unable to pay his debts, DeStefano put McDonnell to work for him, including allegedly (see the account in Captive City by Ovid Demaris) having him carry two dead bodies from his basement. It is extremely unlikely that someone as unstable and unreliable as McDonnell would have been involved by the Outfit in a supposed undertaking of this magnitude and with information this secretive and sensitive. Furthermore, it is difficult to find informed, unbiased individuals who place any faith in statements by Robert McDonnell.

More generally, retired police officers who specialized in organize crime, including former members of the Chicago Police Department’s elite Intelligence Unit, scoff at the notion that non-mobster relatives or peripheral associates of gangsters would have any information about the Outfit that is not publicly available, such as in newspaper articles. Additionally, it must be noted that sensationalism sells books, and that Jeanne Humphreys and Robert McDonnell were each writing a book on the heels of their public claims about the Kennedys, the Mob and the 1960 presidential election — books that would have received considerable attention because of those claims.

It is also worth noting that in the years after 1968, when both John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert were still revered by the public as martyrs, it has become “open season” on the Kennedy family. Nothing sells books faster in recent years than juicy allegations, whether they are supported by convincing evidence or not, concerning members of the Kennedy clan, the Mob, the Rat Pack, and Marilyn Monroe. Such is the world we live in — in which readers need to examine the latest (or the most frequently repeated) sensational claims before giving them any credibility.

Evidence from voting in the election

Obviously, there is considerable disagreement about the Outfit’s role in the 1960 election. While analyzing the sources’ credibility and the plausibility of their claims provides insight into the issue, direct evidence comes from data on voting in the election itself. If the Outfit elected John Kennedy, then Outfit-controlled political districts around Chicago or labor union members influenced by the Outfit must have voted unusually heavily Democratic in 1960.

In statistical tests, I have examined voting by four groups of wards and suburbs where the Outfit would have been most able to deliver votes for Kennedy if it so desired: the five Outfit-controlled wards mentioned above, those five wards and the 45th ward (mentioned by O’Connor), the five Outfit wards and the two premier Outfit-controlled suburbs, Chicago Heights and Cicero, and all six of these Chicago wards and the two suburbs. In each case the percentage of voters casting a Democratic ballot in 1960 is compared not only to the percentage voting Democratic in the previous (1956) or the next (1964) presidential election, but also to how the other wards in Chicago voted in 1960 versus the comparison election. That is, eight separate tests were done with the local voting data to determine if Outfit-influenced political districts voted (everything else being equal) unusually heavily Democratic in 1960.

In only one of eight cases is there evidence of unusually strong Democratic voting that might be due to organized crime. This weak result may be due to chance — that is, it is caused by other random factors that affected voting from one election to the next. Or at most it indicates that the Outfit had a negligible effect on voting in these districts, as Brashler and Roemer argue. It certainly is not consistent with an all-out effort by the Outfit to elect Kennedy, because in that case increased Democratic voting should be evident in more than just 12.5 percent (one of eight) of the tests.

While the statistical tests are by their very nature complicated, the flavor of the results can be obtained by looking at changes in the percentage of the vote cast for the Democratic candidate across presidential elections. The table that follows reports the Democratic percentages in the 1956 and 1960 presidential elections for three groups of political districts: the five Outfit-controlled wards in Chicago, the other 45 wards in the city, and the two premier Outfit-controlled suburbs.

Percentage of votes cast for the Democratic presidential candidate:

| 1956 | 1960 | |

|---|---|---|

| Outfit Wards (1, 24, 25, 28 and 29) | 70% | 83% |

| Other 45 Chicago Wards | 47% | 62% |

| Chicago Heights and Cicero | 34% | 50% |

Certainly, the five Outfit wards and these two suburbs voted more heavily Democratic in 1960 than in 1956. But so did Chicago, as well as the rest of the country in general, as evidenced by the other 45 wards in the city. The increases elsewhere in Chicago are fairly similar, although the percentage voting Democratic increased more (by 15 percent, from 47 percent to 62 percent) in the other parts of the city than it did in the Outfit-controlled wards (where it changed by 13 percent). This simply indicates that JFK was a more popular candidate in 1960 relative to his Republican opponent than Adlai Stevenson was in 1956, when he ran against President Dwight Eisenhower, and/or that county wide the Daley Democratic Machine worked harder for the party’s candidate in 1960 than in 1956. There is nothing in the raw percentages that shows that anything happened in the Outfit-controlled political districts in 1960 beyond what was going on elsewhere around Chicago, given that these five wards voted heavily Democratic in every election (including 1956) for several decades. Similar results are obtained when 1960 is compared to 1964.

However, analysis of the 1960 presidential voting in isolation ignores important local political issues that may cause the preceding results, as weak as they are, to be biased in favor of assertions the Outfit worked for Kennedy. The regular election for Cook County State’s Attorney also took place in November 1960. During the previous four years the Republican incumbent, Benjamin Adamowski, was a thorn in the side of the Outfit, raiding gambling joints in Cicero and strip clubs in Calumet City, and City Hall. It was widely believed that Adamowski, if re-elected as the State’s Attorney, would expose further crime and corruption, especially on the heels of a major scandal in the Chicago Police Department in 1959, and then run for mayor against Richard Daley in 1963.

The Outfit worked extremely hard against Adamowski and, therefore, in support of his Democratic opponent, Dan Ward, in November 1960. Defeated by only 25,000 votes, Adamowski charged that there was widespread vote fraud, and he named 10 wards in Chicago as the worst offenders. Four of these wards were Outfit controlled. If some of this effort involved straight ticket voting, legal or fraudulent, as the Cook County Republican Party chairman claimed occurred with Democratic precincts captains pulling the voting machine levers for illegal voters, then the efforts against Adamowski contributed votes to Kennedy as a side effect.

A recount of about 490,000 paper ballots, in which Adamowski gained 6,186 votes but Nixon gained only 943 votes, showed that the vote fraud was principally directed at Adamowski. While these figures (covering 863 paper ballot precincts), along with the claims about voting machine irregularities, support the contention the Outfit focus on defeating Adamowski resulted in some votes for Kennedy, more direct evidence can be obtained by further examination of the election results. Statistical analysis of voting by the Outfit-influenced wards/suburbs in the State’s Attorney election versus the presidential election finds evidence in all four tests that these political districts voted much more strongly for Dan Ward than they did for John Kennedy when general voting patterns are controlled for. Because of straight ticket voting, some of this effort spilled over to Kennedy, causing the weak pro-Kennedy results in the tests that analyze presidential election results.

The Outfit’s efforts for Kennedy were nothing like what they were capable of, as demonstrated by the unusually heavy pluralities for Dan Ward than for John Kennedy. Similar statistical tests show that the Outfit wards strongly delivered votes for Richard Daley, because the Mob greatly feared his Republican opponent Robert Merriam in the 1955 mayoral election because Merriam campaigned vigorously against crime and corruption. Therefore, the Outfit was quite capable of producing votes in certain areas when it wanted to. It simply was not interested in doing that for Kennedy.

If the Outfit did not get out the vote for Kennedy in its own backyard, where it had control of the political apparatus, it is hard to believe it did so elsewhere. Nonetheless, further statistical tests examine voting by union members nationally. There is no evidence that union members around the country or in states where the Outfit at least partially controlled organized crime activities, such as labor racketeering, voted unusually heavily Democratic in the 1960 presidential election. In fact, there is evidence that union members in states where the Outfit operated voted less heavily Democratic than usual and therefore against JFK, as Len O’Connor suggests.

Before closing this article, one important distinction must be made because there is often confusion on this point. The fact that the Outfit did not deliver on Election Day for Kennedy does not mean that the Cook County Democratic Party Machine led by Richard J. Daley did not pull out all the stops for JFK. The Machine may well have gotten living and dead humans and a variety of fictitious individuals (by making up identities for fraudulent voters) to vote for JFK. Illegal as some of this might be, that is what political machines do — come hell or high water they deliver votes for their party’s candidates. In fact, the Cook County Democratic Machine was famous for its ability to deliver votes. As a show of gratitude Mayor Daley and his family were the first people invited by the new president to stay at the White House.

This also does not mean that Joseph Kennedy, the father of John Kennedy, did not spend lavishly to get out the vote for his son in various parts of the country — that is what backers of political candidates do. However, the Outfit is not Joseph Kennedy. Nor is it identical to the Democratic Party in Cook County. At the time the Outfit controlled the Democratic Party apparatus in only five of Chicago’s 50 wards and in a few, if any, of the suburbs. Therefore, the analysis in this article in no way negates the separate claims that the Daley Machine or Joseph Kennedy did everything possible to elect JFK president.

Conclusion

A famous story from the world of horse racing concerns a supposedly fixed race. Various people “knew” which horse would win and they all bet accordingly. Unfortunately, that horse did not win, prompting one unhappy bettor to remark, “Someone forgot to tell the horse.”

Several extreme claims have been made about the role of the Chicago Outfit in the 1960 presidential election. Like many conspiracy theories, these stories are tantalizing to many people because they suggest a world in which the rich and powerful are pulling strings behind the scenes to make things happen. But these claims lack plausibility when carefully examined, and the sources are far from credible. Even more important, someone apparently “forgot to tell the voters.” Seasoned politicians such as the Kennedys would have recognized that, if anything, Outfit-influenced labor unions voted against John Kennedy, and that the Mob’s behavior locally (in defeating Adamowski) was self-serving. Therefore, they would have owed the Outfit nothing, even if there had been a pre-election agreement.

Clearly, there was no “double cross” when the Kennedy administration intensified the fight against organized crime. In fact, the evidence is inconsistent with the claim that there was a pre-election deal, because the Outfit had nothing to gain by making an agreement and then breaking it. Or, if there was such an agreement, the Outfit double crossed the Kennedys by not delivering the votes on Election Day. Either way, the Outfit certainly had no reason to later retaliate against either John or Robert Kennedy, a claim that is at the heart of several conspiracy theories about both of their assassinations.

Therefore, much of what has been written about the Outfit, the 1960 presidential election, and other events involving the Kennedy family appears to be historical myth.

John J. Binder is the author of The Chicago Outfit (2003) and Al Capone’s Beer Wars (2017) as well as various articles on the history of organized crime. He is also a member of The Mob Museum’s Advisory Council and a consultant to the Chicago History Museum. Various individuals, especially Art Bilek, Bill Brashler, Mars Eghigian, Mickey Lombardo, Matt and Christine Luzi, Tim Perri, Vince Sacco, and Jeff Thurston, provided comments and suggestions that improved this article. To contact Binder, email him at jbinder@uic.edu.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org