Defiance of Kefauver Committee put Frank Costello behind bars for 14 months

Seventy years ago, the ‘Prime Minister of the Underworld’ walked out of a Michigan prison

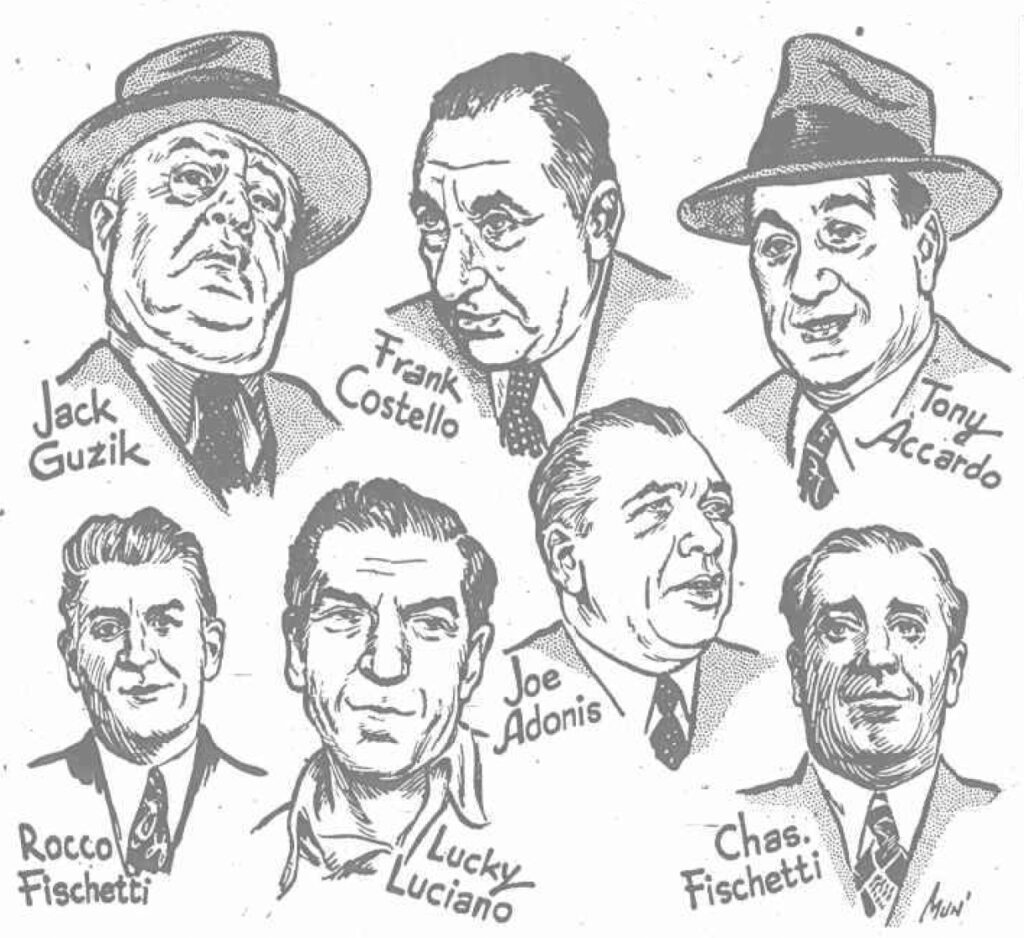

When New York underworld boss Frank Costello famously walked out while being questioned by the Kefauver Committee in 1951, he may not have fully understood the implications of his actions. Or maybe he did. Either way, he was charged with contempt of court and sentenced to 18 months in prison.

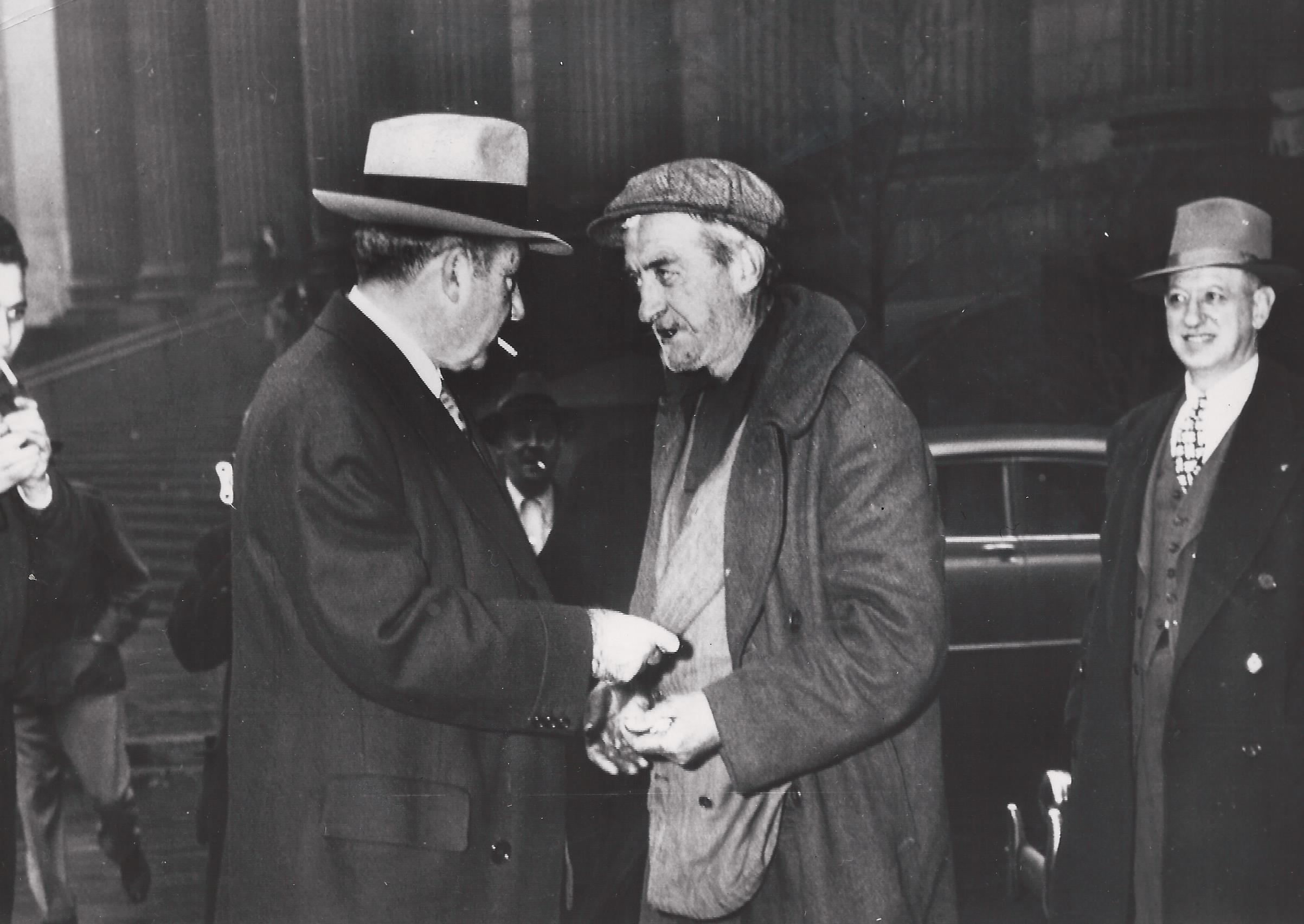

On October 29, 1953 – 70 years ago this month – Costello, once dubbed by Treasury agents as the “Prime Minister of the Underworld,” exited a federal prison in Michigan after serving about 14 months of his 18-month sentence.

Costello’s record reflected a few stints in jail as a younger man but he managed to avoid any lengthy prison for decades (the closest call was a tax evasion charge in October 1939 that was dismissed). That winning streak began to fizzle out on March 15, 1951, when, as a witness before Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver’s Special Committee on Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, he refused to answer any more questions.

The responses he had previously provided were evasive at best, arguably hostile at worst. Costello’s refusal to answer questions regarding his net worth or about his relationship with William O’Dwyer (the former district attorney in charge of the Murder Inc. prosecutions) particularly drew the ire of the presiding senators.

Eventually Costello made it clear he wanted no more part in the proceedings.

“Am I under arrest?” he asked.

“No,” replied Rudolph Halley, the committee’s chief counsel.

“Then I am walking out,” Costello fired back.

Costello defiantly stood up, but stopped short of fully exiting the hearing room while a brief period of exchanges ensued, culminating with Costello’s attorney stating that his client had “acute laryngotracheitis” and producing a doctor’s note recommending bed rest. The committee wasn’t satisfied with the excuse and reminded Costello that he was under subpoena to appear and that leaving would be in violation. Despite the warning, Costello, with his lawyer in tow, left the room.

The incident left the senators in dismay, while producing deliciously scandalous fodder for the press to exploit. In contrast to the closed preliminary hearings held a month before, the committee hearings on New York organized crime were opened to photographers, reporters and TV cameras, thus making it quite a public affair. At that time, roughly half of American households had a television set. The live televised hearings placed subpoenaed mobsters in the visual spotlight as well as the committee itself.

Costello wasn’t the only big name scheduled to appear before the committee in New York. Others called to testify included Frank Erickson, Joe Adonis, William O’Dwyer and Virginia Hill. Costello requested that only his hands would appear on camera, and it was approved. Of course, there are many photos of him that appeared in newspapers and newsreels, but for TV viewers, they only got to see his fidgeting hands and hear his raspy voice.

To Costello’s dismay, the committee’s threats were not idle. It filed 11 contempt charges with the U.S. attorney, and Costello was brought to trial in January 1952. The jurors were deadlocked but a second jury convicted Costello on 10 counts. He was sentenced to 18 months in federal prison, plus a $5,000 fine (later reduced to $2,000 on appeal). Costello went to the U.S. Courthouse in New York and surrendered to U.S. Marshal Tom Farley at 10:10 a.m. Friday, August 15, 1952.

“Tell the boys I have come in to do my bit,” Costello announced to surrounding reporters. “I don’t want no favors from nobody. I wanted to be treated like everybody else.”

Costello was moved around several prisons before winding up in the federal institution at Milan, Michigan, on December 27, 1952, where he served out the rest of his sentence. Milan was a minimum-security penitentiary. Previously, Costello had been held in maximum-security facilities, including Atlanta’s federal pen, but the grounds for his conviction were deemed suitable to be served in what the press called a “common jail” facility.

Upon his release from the Michigan prison on October 29, 1953, Costello was greeted by his wife and whisked away by car, doing his best to lose pursuing reporters. They boarded a train in Detroit and arrived in New York the next day, but not without a dose of token Costello cleverness. The couple didn’t arrive at the predicted destination – Grand Central Station – where reporters eagerly awaited. Instead, they disembarked at a junction in Westchester County and took a car back to Manhattan.

Costello was out of prison, but his legal troubles weren’t over. The government had already been actively looking to challenge Costello’s U.S. citizenship, and another tax evasion case was looming.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad and LUCKY, a gangster graphic novel.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org