Decades of temperance activism led to passage of Prohibition 100 years ago

Advocates used propaganda to build support for liquor ban, but public could not resist Mob’s underground booze market

All the tumult of 2020 makes it easy to forget that it is a huge anniversary in the history of organized crime. Just two and a half weeks into 1920, Prohibition officially began in the United States, the culmination of efforts to curtail or ban alcoholic beverages that had started with the temperance movement in the late 1700s. Over a century of changing priorities and evolving goals, the initial cause of individual moderation in the consumption of alcohol transformed into a drive to ban the trade and manufacture of it altogether, first at local levels, then in several states, and finally at the national level by way of a constitutional amendment.

Prohibition led to vast bootlegging and rum-running empires around the United States that made racketeers rich and powerful. The quick rise of bootleggers that followed Prohibition demonstrates, even more clearly than political arguments, that there was a large segment of the populace that was not in favor of the 18th Amendment. But after nearly a century of campaigning and propaganda, temperance proponents had convinced enough of the American people, and the politicians who served them, to enact it.

As with most social and political movements, temperance and Prohibition advocates used propaganda to get their message to the masses. Some themes remained popular over very long periods, with only slight changes to reflect changing times and the shifting aims of temperance advocates and Prohibitionists.

The temperance movement grew out of a wave of increased religious fervor in the early 1800s, known as the Second Great Awakening. However, by the middle of the 19th century, much of the propaganda was not explicitly aimed at the religious aspect of temperance. To some extent, advocates for spreading temperance believed that a more moral society would naturally develop into a more godly society, and focused on the societal cost of liquor rather than the spiritual aspects.

In the mid-19th century, common appeals to temperance often involved home life. The increase in after-work saloon drinking often led to strife in the family home. For temperance crusaders, the drunken worker returning home and abusing his family was a potent idea used as a cautionary tale in favor of temperance. A popular picture published in 1847 showed a home with overturned table and chairs. The drunken father is presented in mid-assault upon his wife and with the couple’s children fruitlessly trying to restrain him. This specific image was so popular that it was redrawn with minor changes and republished numerous times.

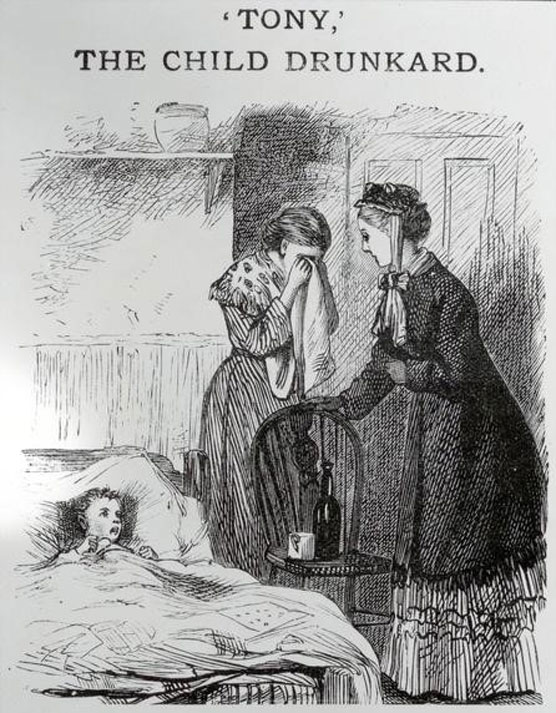

Children also could be the direct victims of drink in temperance propaganda. An image titled “Tony, The Child Drunkard” portrays the heartbreak of a mother as her son lies in bed. The boy is in a drunken stupor, driving home the negative impact of alcohol on family life.

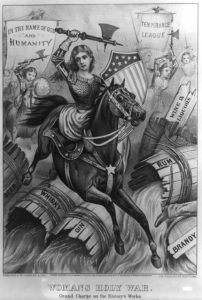

The temperance crusade, likened to a holy war against the corrupting influences of alcohol, waged its mid-19th century campaigns against saloons through demonstrations and public pressure. Women played an especially public role in the temperance crusade. An 1874 picture of women in armor and charging into battle on horses emphasized this. The enemies smashed to pieces by the strokes of their hammers were barrels labeled Rum, Whiskey, Beer and Wine. The lead crusader’s striped and star-spangled shield shows an appeal to patriotism. Her followers bear banners labeling their cause as a holy one, waged by the Temperance League.

Other tactics included public demonstrations and harassment of saloon clientele. Printed booklets of sheet music and lyrics, to be sung in the streets outside targeted establishments, proclaimed the crusaders to be “Mother’s out praying,” who “Strike for the cause of Temperance!”

The tactics could be effective, particularly when the protesters were publicly harassed by the saloon-goers and owners. In 1874, temperance protesters faced trial in Portland, Oregon, for a drunken brawl and riot. They had not participated in the disturbance, but were claimed to have caused it by their protest activities. The trial and short jail sentence gained the temperance crusaders a great deal of sympathy. Follow-up harassment by a local saloon owner swung matters even further in their favor. Portland seemed well on the way to a huge electoral victory for temperance until the very day before elections. A new piece of propaganda was posted around the city on the eve of local elections that struck entirely the wrong tone. The handbill titled the “Voters’ Book of Remembrance” dampened the public sympathies that the temperance crusaders had built up. The text tarred everyone in the city who was not explicitly on the side of temperance as “prostitutes, gamblers, rum sellers, whiskey topers, beer guzzlers, wine bibbers, rum suckers, hoodlums, loafers, and ungodly men.” This poorly timed message transformed an impending temperance victory into a crushing defeat.

The shift in the temperance movement from moderation in drink to legally restricting the sale of alcoholic beverages resulted in the passage of the “Maine Law” in 1851, the first statewide prohibition of the sale of liquor. By 1855, 12 other states had enacted their own versions of the “Maine Law.” Most followed a similar formula, but Texas’ law simply outlawed the sale of liquor in quantities of less than a quart, leaving quite a bit available to those who were prepared to buy in larger volume.

The prohibition laws were not popular with large segments of the population, and in the 1856 presidential election, opponents of Republican candidate John C. Fremont portrayed him as being courted by proponents of the “Maine Law,” alongside other unpopular movements such as “free love,” the influence of the pope, abolition, women’s suffrage and socialism. The cartoon of Fremont readily accepts all of these causes. The mixed bag of allegations made little sense, but they illustrate the general unpopularity of politically mandated temperance at the time.

Temperance supporters advertised their cause in creative ways. Social movements attracted a sort of conspicuous consumption as a way to declare a household’s political ideology and solidarity with a cause. Abolitionist homes, for example, might have a tea set that was marked with abolitionist art and slogans. Often, the container for sugar proclaimed it to be from non-slave labor sugar plantations and was marked with the seals of abolitionist societies. Similarly, decorative plates with temperance themes became popular in temperance households. As with other temperance propaganda, the dissolution of the home and family life was a popular theme, with the women and children brought to ruin or vice, while the fathers had degenerated in moral character to monstrous levels.

Leisure activities also could display and teach moralistic ideals. The original edition of The Game of Life, published by Milton Bradley in 1860, had pitfalls such as “Gambling” and “Idleness,” which brought the player to “Ruin” and “Disgrace,” respectively, while “Intemperance” led to “Poverty.” In the later days of the temperance movement, as prohibition gained ground, supporters of Carry Nation’s “hatchetations” purchased souvenir replicas of her famous hatchet emblazoned with her name, providing her with funds and buyers with a piece to display their temperance bona fides in their home.

As temperance shifted into prohibition via the enactment of laws banning alcohol, the family continued to be a favorite source of propaganda. Portrayals of women and children as the helpless sufferers of the evils of alcohol tried to tug the voters’ sympathies. Pictures featured innocent children, and urged the reader, “for our sake,” to vote against liquor. The phrasing of the propaganda was carefully constructed and presented as a vote against liquor rather than a vote in favor of societal restrictions. Images of mothers with babies urged the public to “Help me to keep him pure,” and again to vote against the sale of liquor. The implicit ban on any trade in alcoholic beverages is carefully not explicit.

As America became more entangled in world affairs, the approaching involvement in World War I brought a new wave of propaganda. The familiar contrast between liquor and society as seen in the “family vs. alcohol” choice grew to include national security. Where the voter had been urged to vote “for the children” versus voting “for liquor,” now he was presented with the question, “Will you back me, or back the booze?” with an image of an American soldier in the trenches. Exactly how a domestic prohibition on alcohol would aid the soldier is not addressed. Sailors at their guns were portrayed as needing a clear head to do their duties and that “drink hinders.” Photos of training soldiers attacking a trench came with the line, “Let’s all go clean over the top CLEAN, and keep fit to fight in France for Freedom.” The fact that U.S. military men on duty were expected and required to be sober, regardless of the legal status of alcohol in the United States, is conveniently unmentioned.

Other wartime prohibition propaganda focused on the home-front effects of alcohol and the need to keep up domestic support for the war. A prohibition postcard proclaimed the saloon backer to be “a traitor to his country,” in line with the nativist turn against German immigrants and their beer-drinking culture. Alcohol was characterized as an unnecessary distraction for a nation at war. It diverted effort that would be better used in ensuring the flow of needed materiel and logistical support for the war. Booze was quite simply “Non-Essential!”

The proponents of Prohibition succeeded in making it the law of the land, enshrined in the Constitution by the 18th Amendment. But the argument itself did not end. Thousands of soldiers, sailors and Marines returned to the United States right before the amendment was ratified, and many were unhappy about the impending change. Servicemen staged their own protests, with signs such as “4,000,000 American soldiers fought for liberty and were rewarded with Prohibition. How come?” and “To Congress! You care for our crippled soldiers, our morals will care for themselves!”

Later, as the rise of organized crime controlling the illicit trade in alcoholic beverages became a pressing public safety concern, some of the same propaganda themes that had been used by the Prohibition advocates reappeared. This time, the safety of the family and young children in this era of organized crime violence was used by proponents of repeal. A mother and her young children appear gathered around a ballot box, with the tag line, “Their security demands you vote repeal,” in an ironic inversion of the same themes that had been used to enact the 18th Amendment in the first place.

The varied approaches and arguments in temperance propaganda help to shed light on what the true believers in these causes thought, what they feared liquor would do to the nation and the family structure. They also reflect the mindset and worries of at least a part of the American public. Not every working man who went to a saloon on his way home from a shift was a violent brute, nor one who drank to excess, but such things happened enough that it was on the minds of the women of the time, so the propaganda had mental ground to root in and grow. Those real-life examples, whether common or rare, made the family-based arguments among the most effective, as can be inferred from just how long that line of argument stayed around.

Prohibition was repealed in 1933. But remnants still exist today in the varied package and blue laws around the nation. The longest-lived third party in the United States is one that most Americans are completely unaware of, the Prohibition Party, yet it still puts up a candidate in every presidential election, even if that candidate doesn’t qualify to be on many state ballots. The Prohibition Party’s presidential candidate this year is Phil Collins of Las Vegas. Collins, a Navy veteran, will appear on a few state ballots, including those of Colorado and Vermont.

Advocates of temperance still exist, and many argue that the 18th Amendment’s failure was a result of poor enforcement rather than intent. But they aren’t as vocal as they once were: They don’t seem to have much of a propaganda budget these days.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org