Dead men walking: Murder Inc. trio electrocuted at Sing Sing prison eighty years ago

New York claims the only execution of a Mob boss in U.S. history

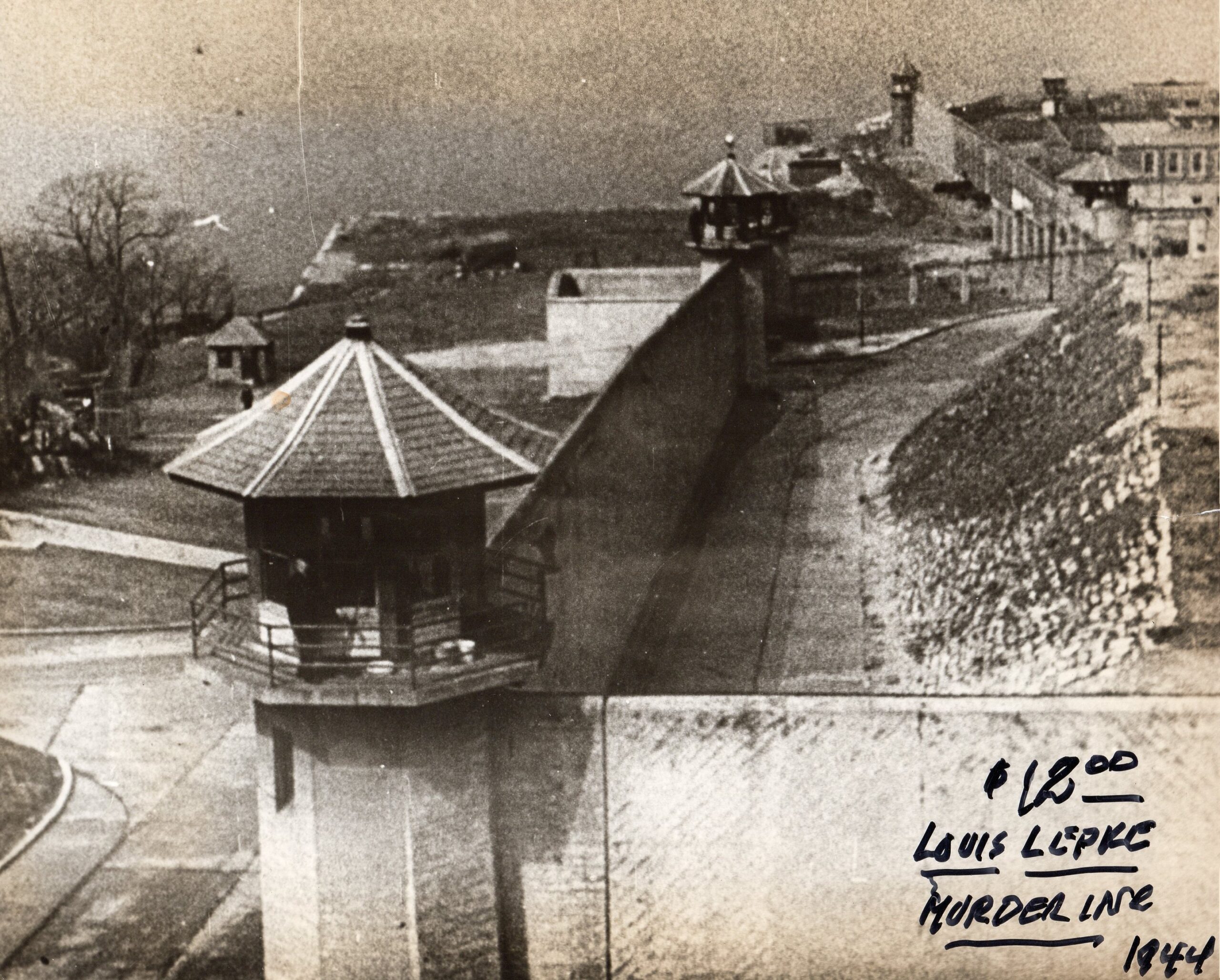

Eighty years ago, Sing Sing’s electric chair, “Old Sparky,” delivered its sinister, life-ending jolts in succession to the trio of Louis Capone, Emanuel “Mendy” Weiss and Louis “Lepke” Buchalter.

The executions on March 4, 1944, marked the climactic close to a particularly bizarre chapter in the Mob’s history. The sensational trials and revelations of the Mob’s violent enforcement arm, better known as Murder Inc., were brought to an electrifying end.

Many defendants were tried across several counties beginning in 1940. Some turned state’s witness, others received lengthy prison terms and seven were put to death. Harry “Pittsburgh Phil” Strauss and Martin “Buggsy” Goldstein were executed in 1941, followed by Harry “Happy” Maione and Frank “Dasher” Abbandando in 1942. Capone, Weiss and Buchalter were the last Murder Inc. defendants to die in the chair.

Doomed from the start

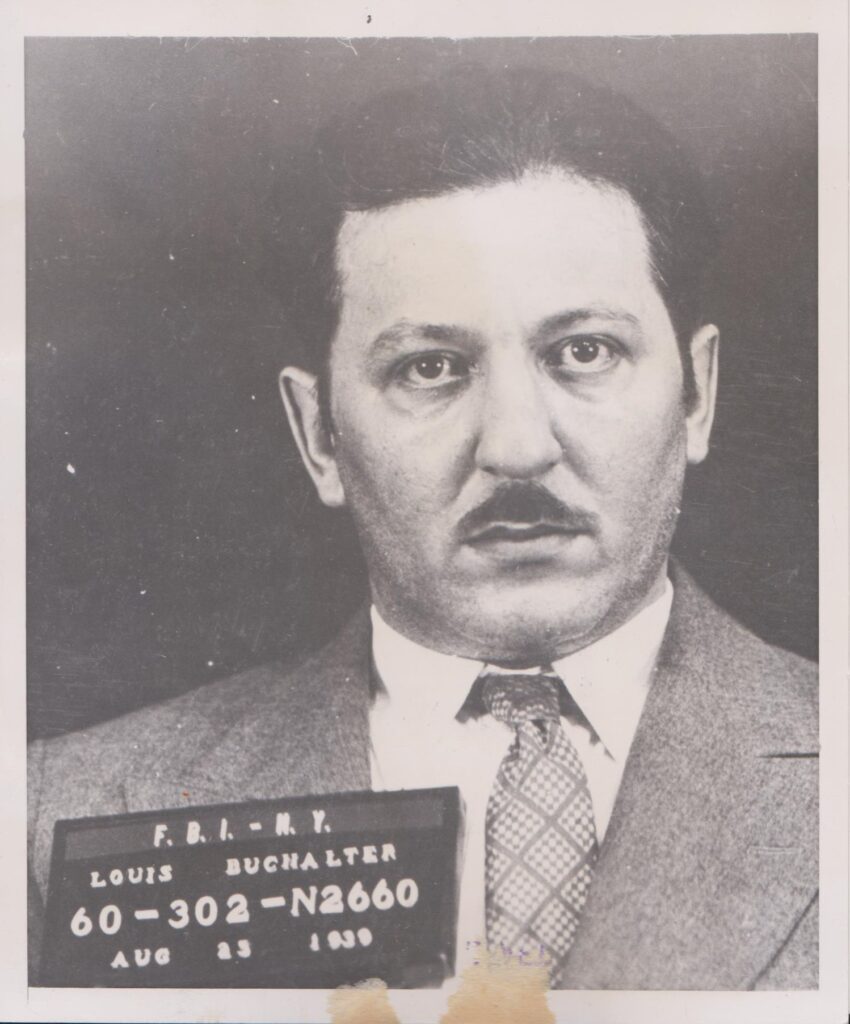

Louis “Lepke” Buchalter’s legal troubles grew dire several years before the shocking discovery of his contract-killing crew. In 1936, he and Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro were out on bail for antitrust law violations in New York when they decided to go on the lam. The feds also wanted Lepke for narcotics trafficking and other charges.

Shapiro surrendered in 1938. Then, in late 1939, Buchalter turned himself in to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. He allegedly believed a deal was in place that would keep him in federal custody, thereby not having to face New York District Attorney Thomas Dewey, who adamantly believed Lepke had been coordinating the murders of loose ends and stool pigeons. There was, however, no such deal, as Lepke would soon find out.

Buchalter took a plea deal in federal court on January 2, 1940. The judge issued a $2,500 fine and sentenced him to 12 years for narcotics trafficking and two years for fur racketeering. Dewey requested Buchalter face trial for the state’s charges. At first, the feds agreed, but a tug of war between state and federal agencies dragged on for some time.

Meanwhile, in Brooklyn, the new DA, William O’Dwyer, put his team, including Assistant DA Burton Turkus, to work on hundreds of cold case murders. Roundups of known hoodlums soon produced turncoats, who revealed the shocking details of a professional contract killing squad based out of a 24-hour candy store in Brownsville, Brooklyn. The group of assassins was known internally as the “Combination” or “Combine” and was, according to informants, overseen by high-ranking mobsters, including Buchalter. The press gave this group a clever name — Murder Inc.

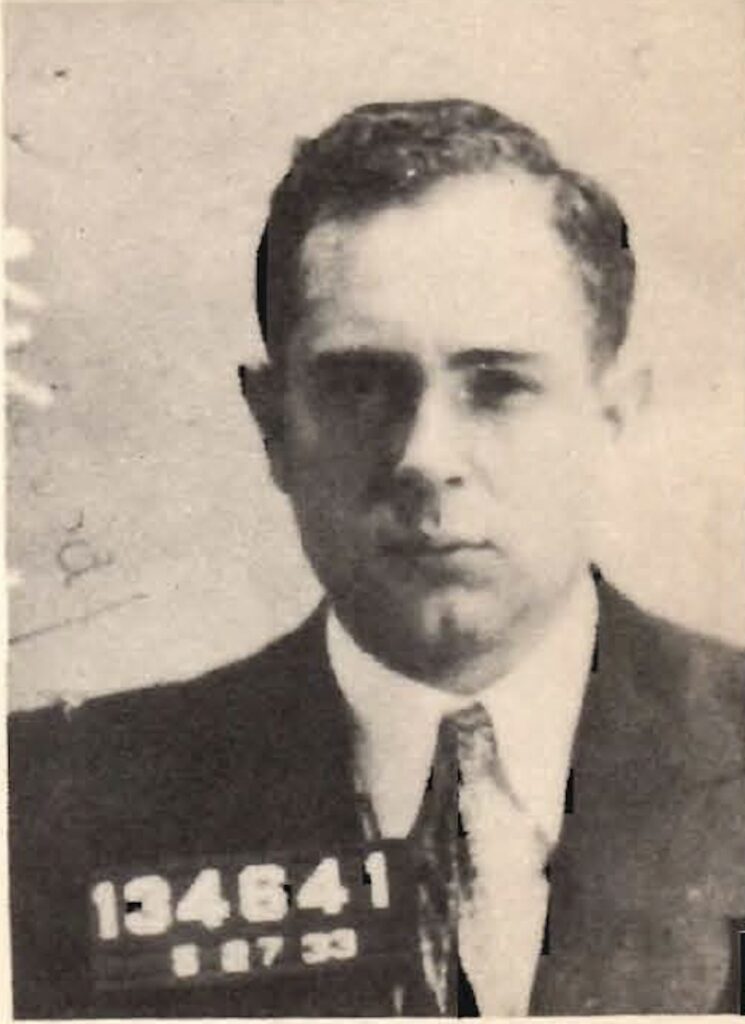

Among the cold cases they reviewed was the murder of shopkeeper Joseph Rosen, shot to death in September 1936. Rosen was forced out of a successful trucking business (allegedly by Buchalter’s faction) before operating a small confectionary. At some point, Rosen spoke up and/or threatened to go to the authorities about the Mob’s strongarm tactics. Former Murder Inc. henchman Abe Reles first told the DA’s team about it. Then, another gunman, Albert Tannenbaum, testified that he overheard Buchalter issue the contract on Rosen. Tannenbaum also named Emanuel Weiss, Louis Capone, Harry Strauss and Philip “Little Farvel” Cohen.

In August 1940, Brooklyn’s prosecutor indicted Buchalter, Weiss, Capone and Cohen. At the time, Buchalter was serving out his federal sentence at Leavenworth Prison in Kansas. Louis Capone’s attorney fought to have his client detached from Buchalter, but Assistant DA Burton Turkus retorted by describing Capone as a six-time killer and the mentor to Murder Inc.’s henchmen. “He raised them from little punks to gang overlords,” Turkus said. “The skull and crossbones flew over Capone’s headquarters.” The motion for a separate trial was denied. Philip Cohen also protested, citing a lack of real evidence and calling out Tannenbaum’s statements as lies.

Over the course of legal red tape and appeals, there were moments when the judges expressed doubt or concern over the flimsiness of some of the evidence against the defendants. But in the end, it didn’t matter.

End of the line

As the Brooklyn proceedings began in September 1941, Philip Cohen’s motion for severance was granted. He would, however, serve out the remainder of his narcotics conviction (only to be gunned down six months after his release in 1949). That left Weiss, Capone and Buchalter to face trial together. All were convicted and sentenced to death. The trial was speedy, but the punishment phase was stymied by appeals, motions and the blame game.

Buchalter’s situation was complex. State authorities bickered with the feds about the terms of handing over their prisoner. The Justice Department wouldn’t turn him over unless the state guaranteed the death penalty, which would require a commutation of his federal sentence by President Franklin Roosevelt. Ultimately, the feds relented, and after three years and six stays of execution, the condemned men finally faced their doom.

On March 4, 1944, the appeals and hopes for clemency were exhausted. The trio said goodbye to family members and ate their final meal. The warden, William E. Snyder, and the electrician (and executioner), Joseph Francel, awaited the first condemned man.

When there’s more than one condemned person, the unwritten protocol is for guards to take the individual perceived as “weakest” first. Louis Capone, escorted by a Catholic priest, entered the death chamber at 11:02 p.m. and was pronounced dead three minutes later.

Mendy Weiss came next, accompanied by a rabbi. Before he was strapped to the chair, Weiss stated that he had been framed and bid farewell to his family. “Give my love to my family and everything else but I am innocent.” He was pronounced dead at 11:11 p.m.

Buchalter, also joined by a rabbi, entered just a few minutes after Weiss’s body was removed. He didn’t speak but glanced around the room at the 36 witnesses.

Reporter Arthur E. Chambers Jr. described the scene in a column for the Daily Argus on March 6, 1944. “To the end, Lepke was different from other condemned men. Instead of wearing black trousers, customarily worn by those going to the chair, he wore his own gray trousers and a white shirt, open at the neck. The regulation tan leather prison slippers and gray wool socks were on his feet. The right leg of the trousers had been slit to the knee to permit attachment of the electrode.”

Lepke was dead at 11:16 p.m.

After the smoke cleared

Buchalter went to his death stoically, with a silence that spoke volumes. Some felt he could have pulled off the veil from politicians and other authorities who may have been in the Mob’s economic sphere.

Lepke’s attorney, J. Bertram Wegman, offered a cryptic statement, open to interpretation: “Buchalter had two keys in his hand. He chose to use the one that opened the door to eternity rather than the other one.”

New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and prosecutor Burton Turkus also weighed in with similarly ambiguous implications. “Some people sweated a lot of bullets in the last few days,” LaGuardia quipped.

Turkus called Lepke’s silence “a signal to the underworld that he was not opening up on its members.”

Buchalter’s execution marked the first and only capital punishment ever carried out on a high-ranking Mob boss in America.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad and LUCKY, a gangster graphic novel.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org