Columbus Day and its ‘Mafia’ origins

Today’s holiday began in response to the 1891 lynchings of 11 Italians in New Orleans

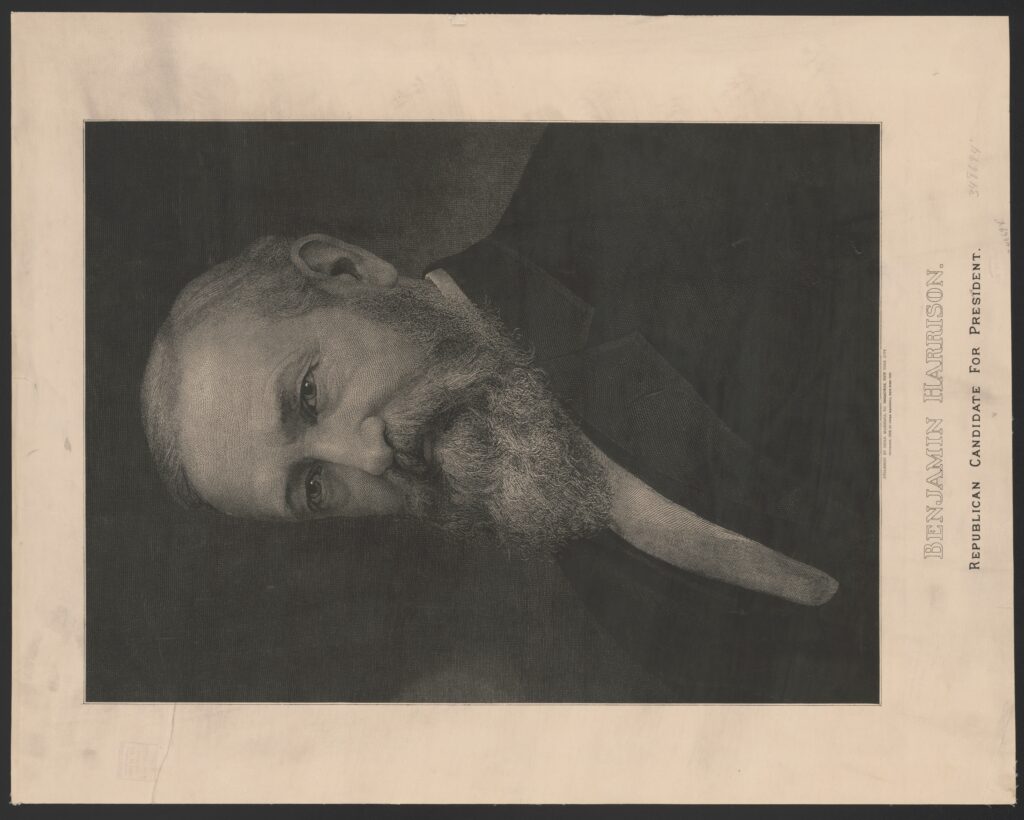

On July 21, 1892, President Benjamin Harrison proclaimed that Friday, October 21st, would be a celebration of the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ discovery of America. But the quadricentennial celebration had a pragmatic origin: It was an attempt in an election year for Harrison to quell anti-Italian sentiments and present an olive branch to both Italy and the Italian American community. The xenophobic hysteria against Italian immigrants had risen to a climax a year earlier.

A storm in New Orleans

In the late 19th century, New Orleans was a popular destination for Italian immigrants. Since the 1830s, the Crescent City had been a port of call for ships carrying Italian citrus fruits, dubbed “lemon boats.” Immigrants arrived in these trade vessels, too. From the 1880s to the 1910s, 60,000 Sicilians migrated to New Orleans, so many that the French Quarter became known as “Little Palermo.”

Like America’s other urban centers, street gangs of thieves and ruffians were a common element in the New Orleans underworld. The influx of Italian immigrants added another ethnicity into the mix. But fears of a secret society of Sicilian mafiosos began to creep into the minds of New Orleans residents. Some Italian criminals, after fleeing Italy to escape prosecution, arrived in the city and further stoked those fears. One of them was Giuseppe Esposito.

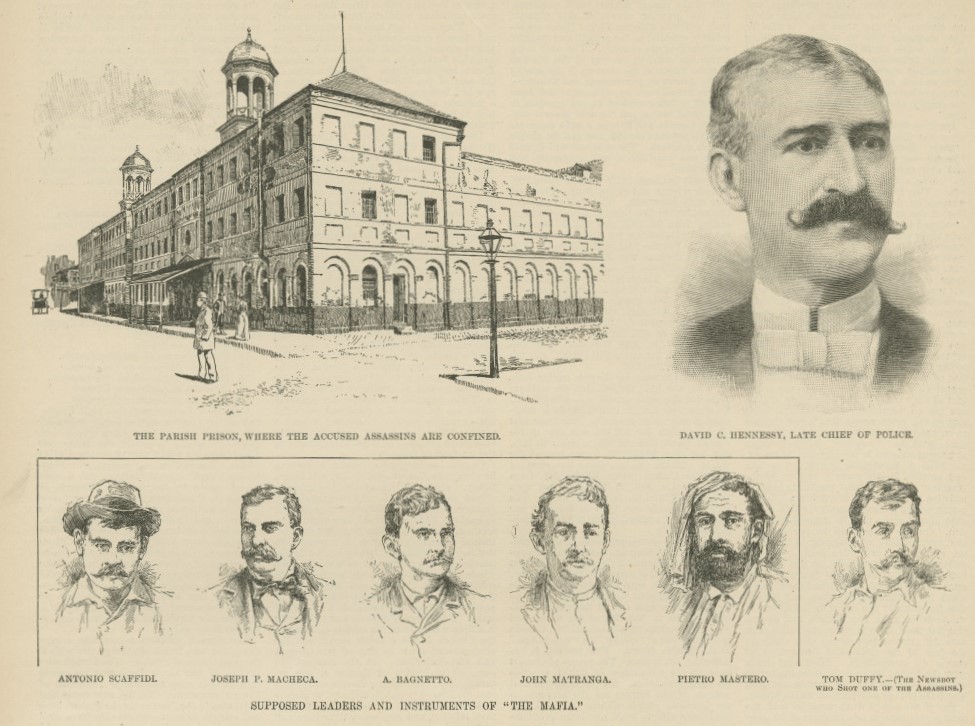

Esposito, a Sicilian kidnapper and extortionist, emigrated after bribing his way out of an Italian jail. Arriving first in New York, he made his way to Little Palermo in New Orleans where he flaunted his outlaw status. Wasting no time, Esposito restarted his kidnapping racket, targeting wealthy Italians in Louisiana. Consequently, his non-furtive presence allowed the Italian government to discover his location in no time. New Orleans Police Detective David Hennessy and his cousin Michael aided two New York detectives in apprehending Esposito, and he was extradited to Italy where he received a life sentence in prison.

This career break for Hennessy was shortlived, however. When he didn’t get a promotion after the Esposito arrest, Hennessy and his cousin Michael shot and killed the chief of detectives, Thomas Devereaux. Claiming self-defense, the Hennessys were acquitted but were fired from the force. Hennessy worked as a private detective until 1888, when the new mayor, Joseph Shakspeare, hired him back, with a promotion to chief of police.

Hennessy became entangled with crime in the Italian community again in May 1890 when a group of dockworkers were shot at and wounded. The victims were members of a stevedore company, the Matrangas. They accused their business rivals, the Provenzanos, of perpetrating the assault. Charles Matranga, leader of the group, started the feud after he edged out the Provenzanos on a ship-unloading contract a few years before. The Matrangas pursued criminal charges against the Provenzanos for the shooting, and six were convicted. Although the word “Mafia” was absent from any court proceedings or law enforcement press releases, the local newspapers used the term frequently.

Hennessy disagreed with the verdict, primarily because of his relationship with the Provenzanos. He had been friendly with the group and allegedly involved in their brothel side business. In the Provenzano trial, Hennessy provided witnesses from the police force to back up the defendants’ alibis. After the guilty verdicts, he pledged to aid in their appeal. It was even rumored that Hennessy would testify himself, but that would never happen.

On October 15, 1890, four days before the retrial, Hennessy was walking home when a group of assassins ambushed him. Wielding sawed-off shotguns, they shot him multiple times before running off. Hennessy died 10 hours later. He only offered one clue as to who did it: “The Dagoes shot me.”

The lynch mob

Immediately, New Orleans Police began rounding up any Italians who were slightly suspicious, including any who possessed a firearm. Mayor Shakspeare ordered them to “arrest every Italian you come across, if necessary.” He also organized the Committee of Fifty, a citizens’ group to investigate and eliminate “Mafia” groups in the Crescent City. The main suspicion fell on anyone remotely associated with the Matrangas, who certainly had a motive for taking out a top Provenzano ally.

While accusations of “Mafia” were thrown around, it is not clear that any of the Italian American players were members of a secret society imported from Sicily. The Matrangas and Provenzanos were stevedores who dabbled in vice rackets. They went to the court system to settle their disputes against one another, not typical for those who adhere to the Mafia’s strict code of silence, omertà. The factions used “Mafia” as a way to disparage each other. Shakspeares’ Mafia crusade was born from nativist fervor rather than actual evidence. Nevertheless, the prevailing anti-Italian sentiments in the community expected that the courts would avenge the slain chief of police.

Most of those arrested were released, save for 19 who remained in jail to await trial. Of the nine who went to trial in February 1891, six were acquitted, including Charles Matranga, while a hung jury resulted in a mistrial for the others. Outraged, the Committee of Fifty organized a public meeting the following morning to decide what to do next.

William Parkerson, a local attorney, political leader and ally of the mayor, addressed the crowd of thousands of angry citizens:

“When courts fail, the people must act. What protection or assurance of protection is there left us when the very head of our police department, our chief of police, is assassinated in our very midst by the Mafia society and his assassins are again turned loose on the community? Will every man here follow me and see the murder of Hennessy avenged?”

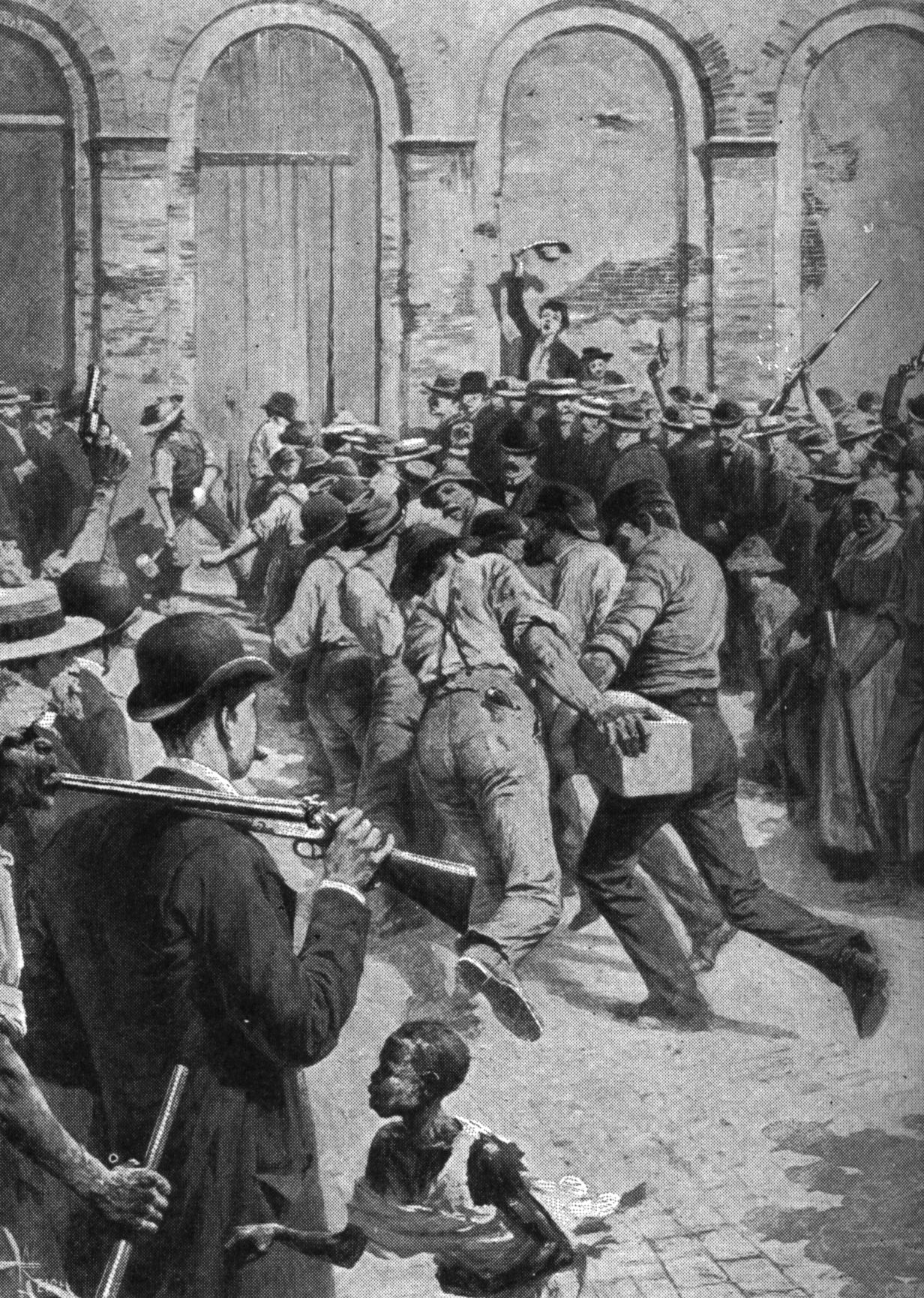

The mob responded by marching to the Orleans Parish Prison. The swarm of belligerents easily breached the walls of the jail. The mob proceeding to lynch 11 of the prisoners, shooting them to death. One of the victims was reportedly shot 42 times. The mob took two of the prisoners who didn’t immediately perish from their wounds and hung them outside the jail. Eight prisoners escaped the carnage, including Matranga, who hid under a mattress.

Newspapers in New Orleans praised the lynchings, but publications in other states condemned them, while conceding it was a necessary evil. Most bought into the idea that the Italian community harbored “bandits and assassins” who had to be stopped even if it came to mob justice. In a letter to his sister dated a week after the lynchings, future U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt wrote: “Various dago diplomats were present, all much wrought up by the lynching of the Italians in New Orleans. Personally I think it a rather good thing, and said so.”

The Italian consul in New Orleans, Pasquale Corte, petitioned Mayor Shakspeare and the Louisiana governor to bring in the National Guard, to no avail. Corte later revealed that he had given the prosecution in the Hennessy case a lead on a group of Americans implicated in the chief of police’s murder, which they disregarded. Immediately after the mob’s assault, he sent a telegram to Baron Francesco Saverio Fava, Italy’s first ambassador to the United States:

“Mob led by members of committee of fifty took possession of jail; killed eleven prisoners; three Italians, others naturalized. I hold mayor responsible. Fear further murders. I am also in great danger. Reports follow.”

Sava and the Italian prime minister reached out to Secretary of State James Blaine, whose defiant stance created an impasse. Italy was outraged by the lynchings, particularly because three of the victims were Italian nationals. Both countries recalled their respective ambassadors. Further stoking the flames, members of Italy’s parliament introduced a resolution calling for a retributive naval assault on the Eastern Seaboard. President Harrison had an international crisis on his hands.

President Harrison’s damage control

Harrison was already facing a difficult battle in the upcoming 1892 election. Although he had a comfortable electoral lead in the 1888 election, incumbent Grover Cleveland narrowly won the popular vote. Undeterred by his defeat, the former president was determined to get back into the Oval Office. In the leadup to 1892, Cleveland was gaining momentum for a comeback. If he wanted to clinch the win, Harrison needed the immigrant vote as his saving grace. But the 1891 lynchings in New Orleans delivered a severe blow to his support in the Italian community.

Harrison had Attorney General William Miller launch an investigation into the Hennessy case, which concluded there was no evidence connecting the victims to an alleged Mafia. Furthermore, Miller’s report scrutinized a list of 94 Mafia murders over the last 25 years produced by Mayor Shakspeare and the Committee of Fifty in reaction to the Hennessy murder. Miller found no evidence to link them to a secret Sicilian society, casting doubt on the very existence of the supposed “Mafia.” In the eyes of the Harrison administration, the Mafia was little more than a bogeyman fabricated to justify nativist persecution of Italians.

That’s not to say that there weren’t Italian criminals or gangs in New Orleans. Consul Corte admitted there was a criminal element in the New Orleans Italian community. But the xenophobic fear of a secret Mafia society in the Crescent City was unproven. Charles Matranga, alleged by some to be the founder of the New Orleans crime family, lived his remaining years quietly with no documented criminal activity. Italian organized crime grew in New Orleans in the early 1900s with Black Hand extortion gangs but had no meaningful connection to the Matrangas.

The president resolved the international conflict with a $25,000 indemnity payment to the Italian government. With the issue behind them, Italy proceeded with its plan to gift a statue of Christopher Columbus (Cristoforo Colombo, to them) to the United States to commemorate the quadricentennial of Columbus’ landing in America. After the statue was installed on a traffic circle at the southwest corner of Central Park, the area became known as Columbus Circle. Nearly 80 years later, New York Mob boss Joe Colombo was shot and left with permanent brain damage about 100 feet from the statue.

Harrison still had to deal with outrage in the Italian American community. On July 21, 1892, his proclamation of “Discovery Day,” a one-time celebration of Columbus, served as an apology and a formalization of an event already celebrated in Catholic and Italian communities. The 15th century explorer was a revered figure in those circles, with celebrations already happening every year across the country. The Knights of Columbus organization, founded in 1882, further promoted these festivities as a rallying point to unite American Catholics, who faced opposition from the Protestant majority.

Harrison’s last-ditch effort proved unsuccessful. Cleveland defeated Harrison in a landslide victory. While it was the end for Harrison, Columbus Day was just beginning.

The Knights of Columbus lobbied for the day to become a yearly tradition, and in 1934, President Franklin Roosevelt declared October 12 as Columbus Day. In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson signed legislation making it an official federal holiday beginning in 1971, now occurring on the second Monday of October.

While today’s holiday has become a point of contention regarding its namesake, its origins had little to do with 1492. It emerged as a recognition of the Italian American and Catholic communities, established by a president who urgently needed support in an upcoming election. And it remains an opportunity to memorialize the 11 Italians slain in 1891, victims of an angry mob that saw Italian immigration as nothing more than a pipeline of criminals invading New Orleans.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org