Chicago crime boss Al Capone transferred to Alcatraz 90 years ago this month

Island prison played host to array of infamous criminals, including mobsters Bumpy Johnson and Whitey Bulger

Depression-era mobsters and outlaws often found themselves locked up in undeniably unpleasant jails and prisons, but being sent to Alcatraz was said to be “the end of the line.” Widely recognized as one of the most iconic correctional institutions in America, and possibly the world, Alcatraz earned the unflattering nicknames of “The Rock” and “America’s Devil’s Island.” The 90th anniversary of the arrival of the prison’s most infamous criminal presents an opportunity to address some of the facts and myths surrounding Alcatraz.

Becoming a federal prison

Long before it joined the Bureau of Prisons, Alcatraz was a desolate island jutting from the San Francisco Bay. The island showed little promise in the eyes of early observers, but by 1854, the island proved otherwise.

In a detailed 1979 report, National Park Service historian Erwin N. Thompson highlighted Alcatraz’s pre-penitentiary years: “On the island stood the first lighthouse on America’s Pacific shores. A light that has guided ships in and out of the magnificent bay for almost 125 years. For nearly 75 years, the island served as a military prison for Army convicts from both the western states and overseas possessions. And for 50 years, Alcatraz played a key role in the defenses of San Francisco.”

Eventually the economic drain on the Army’s budget led to discussions of transition. According to Thompson, the Army “seriously considered abandoning Alcatraz Island” twice in the early 20th century, first in 1906 and again in 1913. But on October 13, 1933, “the third time counted.”

After an agreement was made, the Justice Department began renovations. Some Bay Area residents were not thrilled about having a maximum-security prison in their backyard, but the press and public outcry failed to convince the government to abandon the plans. Alcatraz was officially handed over on June 20, 1934.

When the Justice Department took over, 32 of the Army’s prisoners (described as an “unsavory lot”) remained on Alcatraz. In early August 1934, the first load of federal transfers arrived from the McNeil Island Penitentiary in Washington. Authorities tried to shroud the entire process. The “freight” was described as “pieces of furniture,” but the local press quickly deciphered the code and even managed to confirm the identities of some convicts.

Putting the Al in Alcatraz

The next big shipment of “53 crates of furniture” required additional efforts at secrecy, primarily because of one inmate in the lot. That, of course, was Alphonse Capone. Nobody wanted the security risks nor the chaos that the press and general fanfare would create. Trying to minimize the exposure, authorities played a logistical game of cat and mouse. The train from Atlanta did everything but travel the most direct path. The train arrived in Tiburon, California, where two passenger rail cars were placed on a barge and floated south to Alcatraz on August 22. The men were processed, photographed, inspected for contraband and assigned numbers and cells.

Capone, registered as No. 85, quickly made headlines and thrust Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary into the larger public psyche, which may have been exactly what the bureau hoped. “The feds never explained why Capone was assigned to Alcatraz,” wrote Jonathan Eig in his 2011 book Get Capone, “but it seems fairly clear it was a public relations move.

“It (the federal government) wanted everyone to know that Alcatraz was the toughest slammer in the land.”

Eig contends Capone’s presence in the new prison was publicity gold. “The man got headlines.” They also made a point to treat him just like the other inmates. Unlike his fully furnished cell at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Al Capone did not enjoy any special amenities in Alcatraz.

Although he was noted as a “model prisoner,” his stay at Alcatraz was not without incident. He was assaulted at least once. The attack occurred in June 1936, when inmate James “Tex” Lucas stabbed Capone in the back with shears from the barbershop. The injuries were minor, but the story took on a life of its own, including a version in which Al broke a banjo (sometimes said to be a mandolin or mandola) over Lucas’s head.

Records state that Capone did return a push or punch before a guard intervened. Capone certainly played musical instruments at Alcatraz, but stories of him smashing one over his assailant’s head are most likely false. The story gained traction following the writings of former inmate A.W. Davis in 1937. Other arguably embellished stories about Capone were pushed in paroled inmate Roy Gardner’s tell-all book, Hellcatraz: The Rock of Despair, published in 1939.

Four years into Capone’s term, the effects of improperly treated syphilis were taking a toll. He was treated in the prison hospital until January 1939 when he was transferred to Terminal Island in Los Angeles for a stint, then to Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. He was released on November 16, 1939, and sought treatment at Union Memorial Hospital in Baltimore. In March 1940, Capone drove with his family back to their Palm Island, Florida, home. Capone died at home on January 25, 1947.

Other residents of “the Rock”

Aside from Capone, Alcatraz was home to many other infamous criminals over the course of its service to the Bureau of Prisons:

- Harlem kingpin Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson served most of his heroin trafficking sentence there from 1952 to 1963.

- Before he ascended to the leadership of Boston’s Winter Hill Gang, James “Whitey” Bulger was transferred to Alcatraz while serving an armed robbery sentence. He was there from 1959 to 1962.

- After escaping from federal prison in New York City, con man and counterfeiter Robert V. Miller, aka Count Victor Lustig, served his sentence at Alcatraz from 1935 to 1946. He used more than 60 aliases during his career, although Alcatraz booked him under his birth name.

- George “Machine Gun” Kelly, mastermind of the 1933 Urschel kidnapping, arrived a month after Capone and was there until his transfer to Leavenworth in 1951.

- Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, co-head of the Barker-Karpis Gang, was incarcerated at Alcatraz from 1936 to 1962. He was there longer than any other prisoner in its history.

- Arthur “Doc” Barker, member of the Barker-Karpis Gang, was transferred to Alcatraz in 1935. He was shot and killed during an attempted escape from the island in 1939.

- Los Angeles mobster Mickey Cohen served two stints at Alcatraz between 1961 and 1963, separated by a seven-month reprieve while out on bail.

- Convicted murderer Robert “The Birdman” Stroud spent 17 years in Alcatraz from 1942 to 1959. While imprisoned at Leavenworth, he was permitted to breed birds, but Alcatraz denied him that privilege.

- Roy Gardner, aka “King of the Escape Artists,” served his time on the island from 1934 to 1938. He was the first inmate to write a book about his life in Alcatraz.

Contrary to the long-held belief that only the worst were sent to the island prison, some inmates were not particularly dangerous nor incorrigible. Some were white-collar criminals, and a few were federal inmates who asked for a transfer to Alcatraz for its better living conditions. Capone, while having a reputation for violence, was convicted of tax evasion, which normally would not warrant serving time in a maximum-security prison.

Alcatraz was not a first-stop facility, nor was it an inmate’s last stop — unless he left in a body bag. One had to be transferred to Alcatraz from another facility. Inmates usually transferred to another facility when leaving.

While Alcatraz was known as one of the strictest prisons in the correctional system, there was one upside to living there: Most former prisoner accounts concur the food was much better than at most other facilities.

Escaping the “inescapable” island

Escape attempts, successful and not, have occurred at Alcatraz since its years as an Army detention center. Although it was rumored that Alcatraz had secret tunnels that could have aided prisoner escapes, Park Service historian Thompson reported that a communications tunnel from its fortification days had been sealed up in advance of transitioning to the Bureau of Prisons.

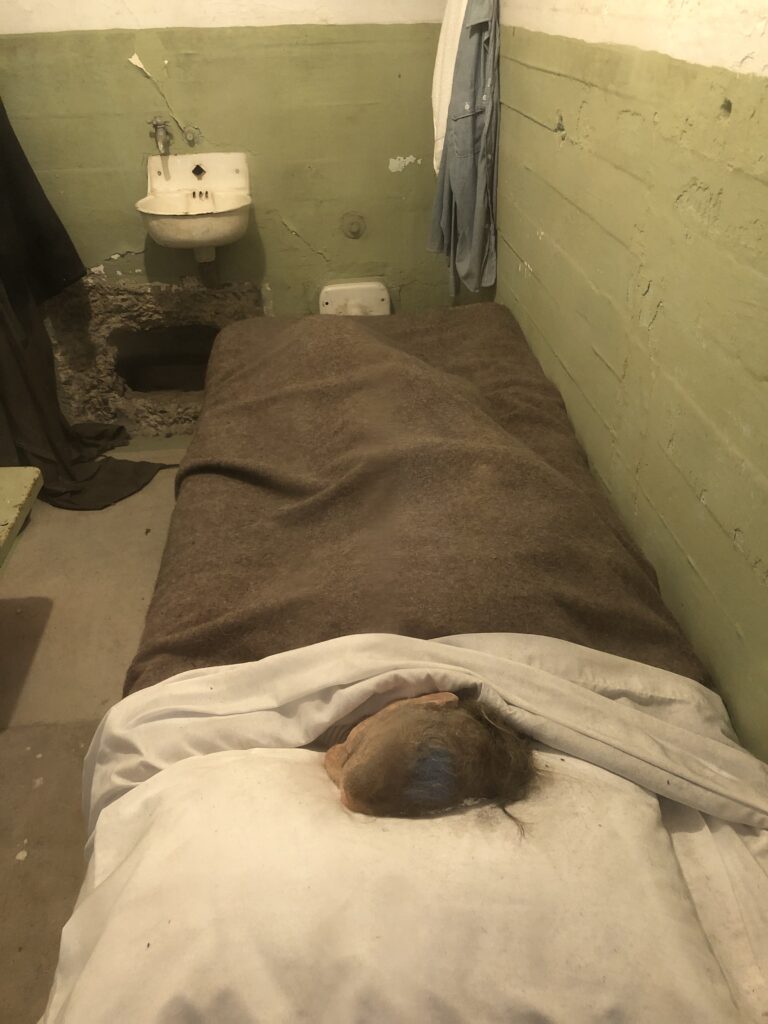

The post-military era documented 14 escape attempts by 36 inmates from 1934 to 1963. The most famous and still controversial one occurred on June 12, 1962. The plot involved John and Clarence Anglin, Frank Morris and Allen West.

As summarized by the FBI, “the routine early-morning bed check turned out to be anything but. Three convicts were not in their cells: John Anglin, his brother Clarence and Frank Morris. In their beds were cleverly built dummy heads made of plaster, flesh-tone paint, and real human hair that apparently fooled the night guards. The prison went into lock-down, and an intensive search began.”

The escapees had spent months chipping away (with stolen and makeshift tools) deteriorating concrete surrounding the vent in the back of each cell to access the utility corridor. West remained behind as he couldn’t squeeze through his vent hole on the eve of the escape. None of the three escapees have been found, only some remnants of the makeshift rafts and other items they had upon entering the turbulent San Francisco Bay waters.

Investigators kept a look-out for the escaped convicts for more than 15 years, but eventually it was time to move on: “The FBI officially closed its case on December 31, 1979, and turned over responsibility to the U.S. Marshals Service, which continues to investigate in the unlikely event the trio is still alive.”

Alcatraz officially closed on March 21, 1963. The last prisoner to walk out of Alcatraz was 29-year-old Frank C. Weatherman, who had been transferred there in 1962 for trying to break out of an Alaskan prison.

The Bureau of Prisons states: “It did not close because of the disappearance of Morris and the Anglins” but rather, as with the Army’s decision decades earlier, had everything to do with economics. “An estimated $3-$5 million was needed just for restoration and maintenance work to keep the prison open. That figure did not include daily operating costs – Alcatraz was nearly three times more expensive to operate than any other federal prison.”

Christian Cipollini is the author of Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad and LUCKY, a gangster graphic novel.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org