“American Gangster,” biopic of Harlem drug kingpin Frank Lucas, celebrates 10-year anniversary

Film’s accuracy subject of intense debate: Were drugs really smuggled in dead soldiers’ caskets?

On this day 10 years ago, the film American Gangster debuted with A-list stars portraying the true story of a high-profile New York City drug lord. It was a sure bet for Hollywood.

Tales of outlaws, renegades and mobsters have a way of tapping into a moviegoer’s inner rebel, creating the opportunity to live vicariously through the antihero’s exploits. It’s exactly why gangsters – of both the real and fictional kind – are good for business in the entertainment realm, from books to television to movies.

American Gangster entered theaters in 2007 to considerable praise from audiences. Rapper Jay-Z paid the movie homage with an entire album. It earned more than $96 million at the box office, ranking among the top-grossing gangster films of all time. It is consistently high on various “best mob movie” lists. But as with any movie, opinions varied. Some real-life characters in the story of Frank Lucas (played by Denzel Washington) disputed the film’s account of the ex-drug dealer’s exploits, most notably the attention-grabbing claim that he used the coffins of American soldiers killed in Vietnam to smuggle heroin into the country.

American Gangster focuses on the relationship in the 1960s and 1970s between Lucas, a prominent Harlem drug lord (later convicted and turned state’s witness), and Richie Roberts (Russell Crowe), the cop obsessed with bringing him to justice. Although touted as a “fictionalized” version of Lucas’ life narrative, the big-budget movie was based on a nonfiction article written by Mark Jacobson for New York magazine. Published in 2000, the now-iconic article, titled “The Return of Superfly,” attracted Hollywood’s attention and put the real Frank Lucas back in the limelight. Amid the predictable denunciations of “glorification” of crime, which come with the territory, some critics appreciated the film.

“It’s a seductive package, crammed with all the on-screen and off-screen talent that big-studio money can buy,” wrote New York Times reviewer Manohla Dargis. “Filled with old soul and remixed funk that evoke the city back in the day, when heroin turned poor streets white and sometimes red.” The iconic movie critic Roger Ebert said the film “is an engrossing story, told smoothly and well.”

Praise for American Gangster, however, largely went to the actors, as even critics who liked the film found flaws. The dissent that carried weight came from those who personally knew Frank Lucas and/or were involved in the same illicit circles.

Notwithstanding the reality and (arguably) necessity of “creative license” taken by Hollywood to bring a real-life story to the screen, the film’s harshest detractors pointed out that not only did it portray some major events incorrectly but Lucas himself provided much of the misinformation to the producers.

It’s almost a given that any film described as biographical, based on true events or a memoir will draw ire from historians and those with intimate knowledge of what really happened. But American Gangster caused an unusually multifaceted uproar. A month after its release, a group of retired federal agents filed a lawsuit against the filmmakers for defamation, claiming agents were depicted falsely. Similarly, several cops who were intimately involved in the Lucas case challenged the film’s depiction of Richie Roberts, saying the latter had little to do with the actual case. Days before the film opened, a trio of former New York cops publicly expressed their anger over the film’s take on Roberts.

“We spent nearly two years risking our lives on that case, and then we see a guy who had no interest before we made the arrests take the credit,” former officer Ed Jones told the New York Daily News in November 2007. “We’re angry.”

Roberts responded to this claim, telling the Daily News, “Sure, they (producers) used a little literary license” and the film did “kind of blur the lines between the time I was a detective and the time I was a prosecutor.”

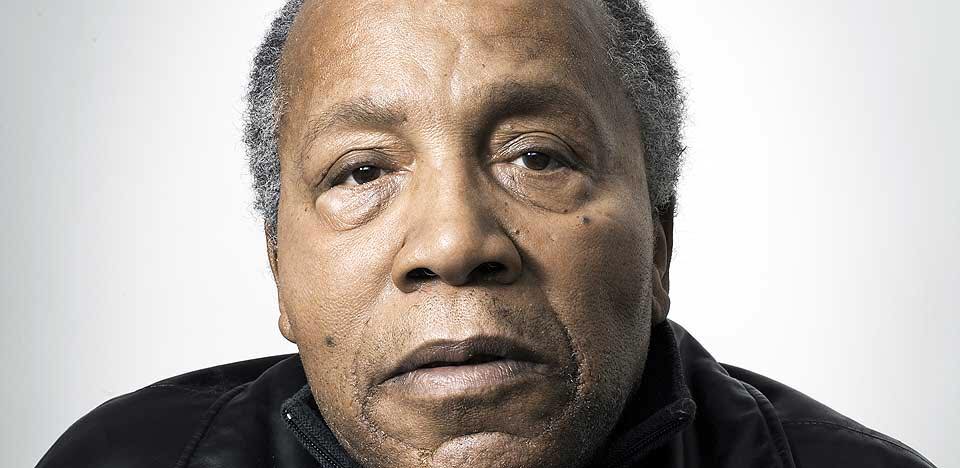

But Lucas himself, now 87 years old, dismissed the cops’ complaints, saying, “I’m not going to credit them with getting me. Those three cops couldn’t catch a cold.”

In the film, and in line with what Lucas recounted in the “Superfly” article, old-time Harlem gangster Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson serves as a mentor to the up-and-coming drug lord, who goes on to become a major supplier of the Far Eastern heroin cleverly smuggled via coffins of American servicemen.

“Not so,” insisted Johnson’s widow in her book, Harlem Godfather: The Rap on My Husband, Ellsworth ‘Bumpy’ Johnson. In the book, Mayme Hatcher Johnson acknowledged Lucas knew and always demonstrated admiration for her late husband, but sharply rebutted the relationship as portrayed by Lucas and the film.

“That’s because Frank Lucas, the dope dealer depicted by Denzel Washington in the movie American Gangster, pretty much took Flash Walker’s relationship with Bumpy and claimed it as his own,” she said.

The real Nicky Barnes also took issue with the film’s accuracy. “I always got my drugs from the Italians,” Barnes, Lucas’s former rival in the heroin trade, told the Daily News in November 2007. “They have this scene where Frank yells at me for using the name of his dope – ‘Blue Magic.’ It never happened!”

Barnes further challenged the film’s big reveal: that Lucas’ organization smuggled heroin from Southeast Asia into the United States via the coffins of dead servicemen.

“His dope never came in the coffins of G.I.s from Vietnam,” Barnes asserted. “Check the public record!”

That sentiment is perhaps the most significant complaint of all. The film’s most haunting, perhaps heartbreaking premise is that Lucas exploited the fatalities of the Vietnam War to run dope – aka “The Cadaver Connection.” But the film is wrong and Barnes was right. The Cadaver Connection story was the product of misreporting dating to the early 1970s.

In December 1972, United Press International reported that anonymous government officials had discovered a vast network of smuggling that included the method of hiding dope in caskets, describing the organization as “ex-GI’s with Southeast Asian experience [who] had infiltrated many levels of the armed forces, including body preparation centers in Vietnam.” The report went on to detail a federal official’s version of the scheme: “Airtight bags (of heroin) could be slipped into bodies after autopsy.”

One of those military men convicted for his role in the heroin ring, Leslie “Ike” Atkinson (portrayed by Roger Guenveur Smith as the character Nate in the film), explained in 2008 how the Cadaver Connection rumor likely started. Atkinson, also known as Sergeant Smack, was convicted in 1974, and in 1987 authorities accused him of continuing to operate the drug ring from his prison cell, crediting him with the sensationalized “Cadaver Connection” scheme. Atkinson said he and his cohorts used teakwood furniture for smuggling.

“In Thailand, while he was there, Frank Lucas came to my house and I introduced him to Leon (Atkinson’s carpenter), simply telling Lucas that Leon was doing carpenter work for me,” Atkinson said, adding that he didn’t want even Lucas to know the real method of smuggling. “Lucas asked Leon what he was doing, and I spoke right up and said Leon was making coffins. That’s probably where Lucas got the whole coffin thing.”

American Gangster was directed by Ridley Scott and was co-written by Steven Zaillian and Marc Jacobson. The film grossed $43,565,135 during its opening weekend in 2007 domestically and another $136,300,392 internationally. It went on to earn 37 film award nominations and 12 awards.

After the film’s release, the real Richie Roberts, who went into private practice as an attorney, represented Lucas in 2011 on a charge of “theft of disability assistance funds.” Lucas was sentenced to probation in that case.

Roberts himself made the news again in April 2017 when he pleaded guilty to charges that his law firm failed to pay payroll taxes.

Christian Cipollini is an organized crime historian and the award-winning author and creator of the comic book series LUCKY, based on the true story of Charles “Lucky” Luciano. Go to www.ganglandlegends.com.

This blog was originally published on November 1, 2017.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org