Gambino crime family boss Paul Castellano murdered outside Manhattan steakhouse 40 years ago

Slaying was first step in John Gotti’s rise to power

Forty years ago, a faction of Gambino crime family members orchestrated and executed a brazen coup to permanently remove their contentious boss, Paul Castellano. On December 16, 1985, assailants shot and killed him in the heart of holiday shopping season in Midtown Manhattan.

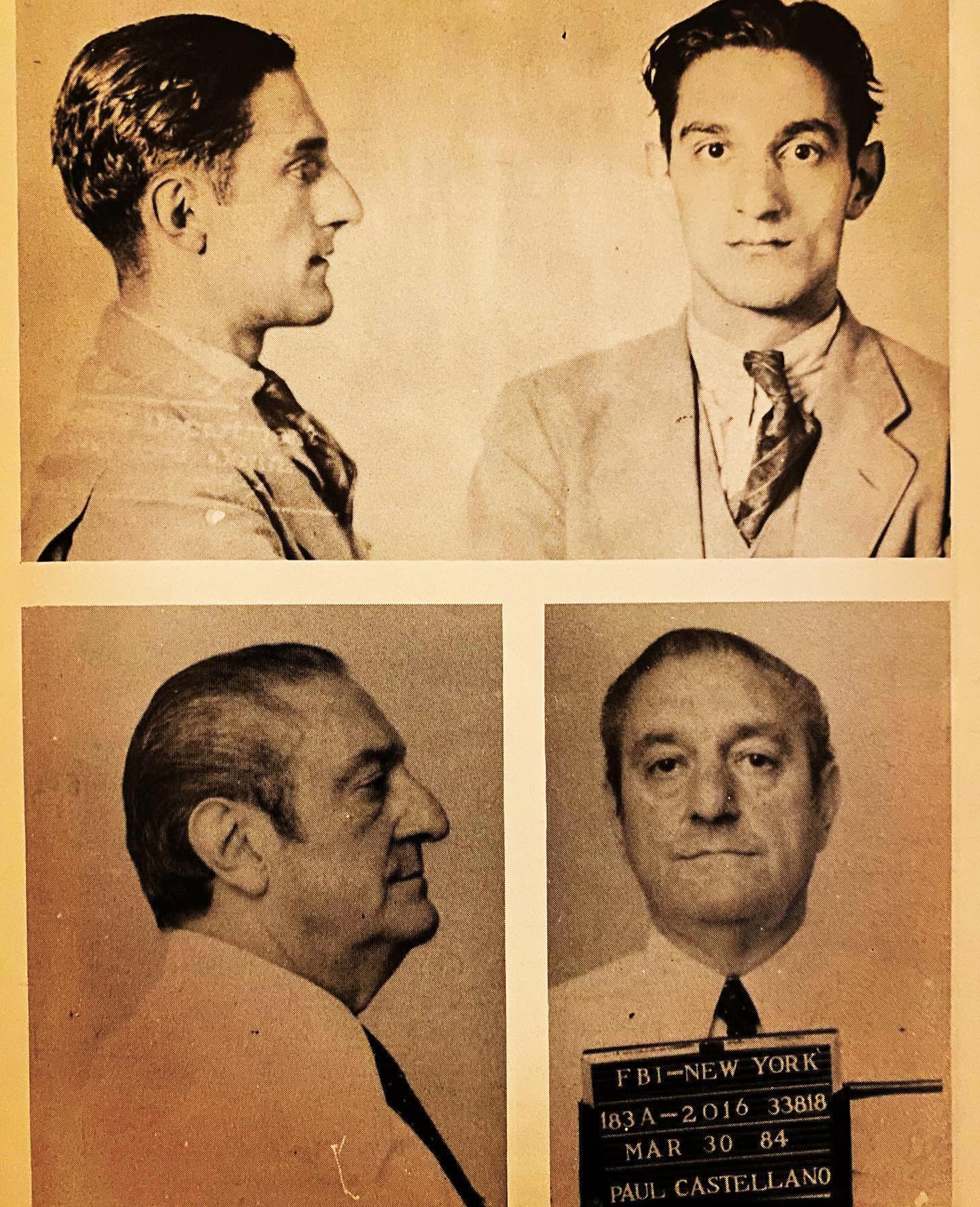

Born in 1915 in Brooklyn to Sicilian immigrants, Castellano grew up in a world under the influence of local Mafia crime families. That also included his own immediate and extended family. He and Carlo Gambino, his first cousin and future boss, also became brothers-in-law after Gambino married Castellano’s sister, Catherine, in 1932.

Castellano’s criminal life began in the 1930s through low-level rackets, but he quickly distinguished himself with his business-minded approach to organized crime. Unlike many of his contemporaries who built reputations on violence, Castellano cultivated political connections, leveraged legitimate-appearing businesses — particularly in construction, meat distribution and trucking — and positioned himself as a modernizer who understood both street operations and white-collar schemes. His combination of family ties, strategic marriages and financial savvy earned him steady promotions within the crime family.

Castellano’s ascent accelerated under Gambino, who trusted his discretion and intellect. Gambino, who became boss in 1957, eventually promoted Castellano to capo and later used him as a key adviser. By the early 1970s, Castellano controlled lucrative construction and union interests and had become one of the family’s primary earners.

Mounting disdain

There was no single reason for some members of the crime family to dislike Castellano. Instead, multiple factors seemed to have accumulated over time, contributing to the dissonance. Among the most significant criticisms began with Castellano’s appointment as boss in 1976 — a decision that bypassed then-underboss Aniello “Neil” Dellacroce, who was in prison at the time.

Gambino’s dying wish designated Castellano as his successor. However, those loyal to Dellacroce found this choice shockingly unconventional and, worse, disrespectful to the underboss, who was well-liked and respected by most soldiers and captains.

Critics within the organization also felt that Castellano lacked the credibility that comes from experience and was disconnected from the street-level hustle that generated the cash envelopes kicked up to the boss. But not everyone harbored such resentment. Some, including a few of the mutineers-to-be, generally regarded Castellano as respectable, at least for a time.

John Gotti, who headed a crew in Queens based at the Bergin Hunt and Fish Club, maintained a close relationship with Dellacroce. He openly expressed his disappointment over Castellano receiving the top position. By the early 1980s, the divide between Gotti’s crew and Castellano became more pronounced and vocal. Dellacroce acted as a buffer between Gotti and Castellano. However, the situation escalated when rumors of “surveillance tapes” reached Castellano.

Reel-to-reel danger

Beginning in 1981, the FBI recorded a series of conversations, unaffectionately known as the “Quack Quack Tapes.” The recordings revealed that a few members of Gotti’s crew had been dealing dope, including Angelo “Quack Quack” Ruggiero, Gotti’s close friend, as well as Gotti’s brother, Gene. Ruggiero was at the heart of this problem, as the bulk of the audio was recorded on a tapped line in his home. After the government tapes captured Ruggiero’s loose lips in astounding candidness, he and Gene found themselves indicted in a federal narcotics case. This was bad news for the family, but it led to bigger internal problems.

Castellano became aware of the wiretap recordings when the indictment was revealed in 1983. Ruggiero’s attorneys had access to portions of the surveillance audio tape transcripts. The recordings featured certain Gambino crime family members discussing drug deals and even mentioning Castellano, including disparaging remarks against the boss.

At first, Castellano did not know much about the actual content of the tapes, except that the indicted members of his crime family may have broken his strict edict — no dope. As bits of information trickled out, his concern and anger grew. He eventually demanded that Ruggiero give up whatever tapes or transcripts he had. Gotti’s crew, however, knew that if Castellano heard the details within those recordings, it would likely result in severe consequences.

The war of attrition placed Dellacroce in a difficult position as he tried to shield Gotti’s crew, who were unwilling to provide the damning evidence, while keeping Castellano’s temper at bay.

The tapes from Ruggiero’s home phone were not the only recordings of notable importance in the lead-up to Castellano’s demise. Foreboding conversations were recorded during a meeting in 1983 at Casa Storta restaurant in Brooklyn on January 23 between Ruggiero and Colombo family capos Gennaro “Gerry Lang” Langella and Dominic “Donny” Montemarano.

Perhaps ironically, the FBI recorded the conversation in pursuit of an entirely different case against Colombo boss Carmine Persico. It just so happened that the casual meeting revealed things nobody put together until after the infamous Castellano hit.

Langella: “Your boss [Castellano] is breaking our ——. This —— is going to —— us. And I’m telling you don’t repeat this because I don’t want anybody to think I’m a wacko. What did I tell you, Donny [Montemarano], after the holidays, what would happen?”

Montemarano: “Neil and Johnny will die.”

Langella: “That’s it. I said I made a prediction, and you know what?”

Montemarano: “Just what you see is going on.”

Ruggiero: “It’s getting worse and worse.”

The trio also discussed a rift between Dellacroce and Castellano, and about Castellano’s frequent tendency to speak ill of “everyone.” Additionally — and possibly without their knowledge at that moment – they subtly hinted at Castellano’s destiny.

Langella: “He ain’t going to get away with it no more, somebody’s gonna—”

Ruggiero: “I know.”

A nearly perfect ambush

Gotti saw a preemptive kill as his only path to survival, but he could not move without broader internal support. Frank DeCicco and Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano became essential players to get that backing. Through whispered networking, the conspirators gauged the other crime families’ stance on an unsanctioned hit of this magnitude. The consensus was not exactly positive, but wasn’t a hard no either.

But there was a problem: Nothing could be done to Castellano while Dellacroce was still alive. Then Dellacroce lost his battle with cancer on December 2, 1985. Making matters worse, Castellano did not attend the wake, citing his legal troubles and desire to lay low.

DeCicco, though tied to Castellano, recognized the growing resentment and understood that the family was at risk of splintering. Ever pragmatic and ambitious, Gravano concluded that backing the hit was the most realistic way to protect his own crew and future within the family.

It was only after Gotti, DeCicco, and Gravano acknowledged that Castellano’s removal was both unavoidable and manageable that they decided to act. The result was not a cohesive conspiratorial group, but a transient coalition of factions, each convinced it had more to lose by remaining inactive.

The date was set, thanks to DeCicco’s insider information. He was to attend a meeting at the Sparks Steak House with Castellano, his underboss Tommy Bilotti and others on December 16, 1985.

According to Gravano, the job consisted of 11 men: four shooters, a few backups and the getaway drivers. They were all Gambinos, and most were “made” men. The shooters wore beige trench coats and “Russian-style” hats (Gravano recalled in a recent podcast that he wasn’t sure but thinks the fashion was Ruggiero’s idea.)

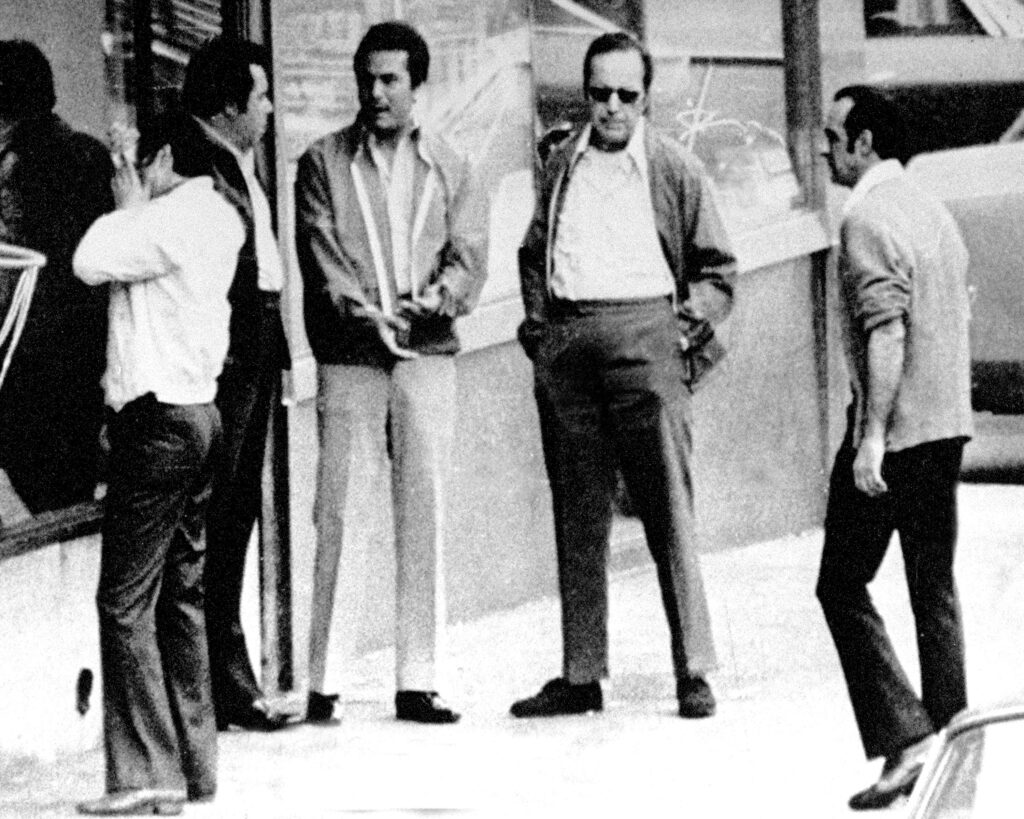

Gotti and Gravano parked across the street from the restaurant. When they spotted Castellano’s car and visibly confirmed that both the boss and underboss were inside, they radioed the team to move in.

At 5:16 p.m., as Castellano exited from the passenger side of the vehicle in front of the restaurant, he was shot multiple times. Bilotti immediately exited the driver’s side attempting to fire back at the assailants, but he was approached from behind and fatally shot.

This all occurred while hundreds of people were in the area, including on-duty and off-duty cops. But the hit went down so quickly and efficiently that there was little anyone could do. The hitmen had walked off and disappeared among the crowds.

Theories began to surface just days after the shocking murder. Ronald Goldstock, executive director of the state’s Organized Crime Task Force, gave his perspective to a reporter at United Press International: “[Castellano] was facing trials and a lifetime in prison. [The Mob] considered him a liability. … He could only bring them harm.”

Others theorized that the coup had the hallmarks of “young turks” ridding the ranks of the old guard. Regardless of which was the most probable theory, the common thread was Gotti, now the de facto kingpin of the Gambinos.

At the time of Castellano’s assassination, the Gambino crime family was both the largest Mafia clan and generally viewed as the most powerful of the Five Families, even though internal tensions and federal pressure were beginning to destabilize it.

Fame and fallout

The bullets outside Sparks didn’t simply end Castellano’s reign; they shattered the fragile underworld balance he had tried to maintain. Gotti’s ascent, forged in that blaze of gunfire, became a turning point the entire Mafia would be forced to navigate. His refusal to hide in the shadows, with his tailored suits and swaggering confidence, drew the public’s fascination and the government’s fury in equal measure.

Almost overnight, the new boss found himself as hunted as he was celebrated, while figures such as Vincent “Chin” Gigante watched the spectacle unfold with cold calculation, determined to strike back for the break in protocol.

In the years that followed, the legend of the “Dapper Don” — and later the “Teflon Don” — would emerge from this collision of bravado, media attention and relentless surveillance. But the murder of Castellano remained the event that set the stage for everything.

When Gravano broke the code of silence and sat before federal prosecutors, the full machinery behind the hit finally came into focus. His testimony mapped out the conspiracy in stark detail, including the meetings, the surveillance and the shooters positioned around the restaurant waiting for Castellano’s car to roll up.

Castellano’s murder stands not only as the moment that elevated Gotti, but arguably as the spark that set in motion the slow, public unraveling of Cosa Nostra. What followed were investigations that decimated the families, internal rivalries that turned deadly and the collapse of a criminal dynasty that once seemed untouchable.

Christian Cipollini is an organized crime historian and the award-winning author and creator of the comic book series LUCKY, based on the true story of Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org