Sixty years ago, Nevada entered the modern era of gambling regulation

Gaming Control Act of 1959 led to blacklisting of mobsters known to frequent Nevada casinos

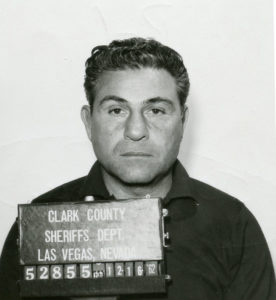

Marshall Caifano, the Chicago Outfit’s overseer of casinos in Las Vegas, went by more than a dozen fake names before changing it legally to John M. Marshall in 1955. Still, the Mob gunman couldn’t hide his criminal record – arrested 35 times, top suspect in more than 10 murders, convictions for larceny and bank robbery. In 1958, before the U.S. Senate’s McClellan Committee investigating organized crime, he pleaded the Fifth 73 times and Congress cited him for contempt.

Since the early 1950s, Caifano had enjoyed cooling his heels in Las Vegas casinos, unmolested. At the start of the 1960s, Nevada would alter his comfortable life – and those of ten other hoodlums – in the gambling capital forever.

Under the political guidance of newly elected Governor Grant Sawyer, the state’s Legislature in March 1959 approved a sweeping new regulatory law, the Nevada Gaming Control Act, a huge first step in transforming how the state policed its licensed casinos to purge them of syndicate types like Caifano. That law took effect on July 1, 1959.

The Gaming Control Act certainly did not prevent the Mob from skimming and otherwise stealing money from state casinos to disperse out of state. That would continue for more than two decades. But it did lead almost immediately to new policies and standards for casinos, anticipated for years but never formally applied. It also brought Nevada some needed credibility. After many national news and magazine articles in the 1950s about mobsters with interests in Nevada casinos or ties to casino owners, the state could now fight back against some of the biggest names in the national syndicate.

The main provision of the act was the creation of a new agency, the five-member Nevada Gaming Commission, assuming the role formerly played by the Nevada Tax Commission. The commission, made up of part-time laypeople, would set gambling policy, give final approval for licenses and supervise the state Gaming Control Board, the full-time investigative body created in 1955.

Under the new law, the governor appointed, as needed, the five Gaming Commission members and three Control Board members. The board would investigate gaming license applicants and licensees, and, the act read, if “the board is satisfied that a license should be suspended, revoked or limited, conditioned, suspended or revoked,” then it would a file a “complaint” with the Gaming Commission. The commission then “shall have full and absolute power and authority to limit, condition, revoke or suspend any license for any cause deemed reasonable.”

Administrative rule by the Gaming Commission and Control Board represented the start of Nevada’s modern gaming regulatory system, still in place 60 years later.

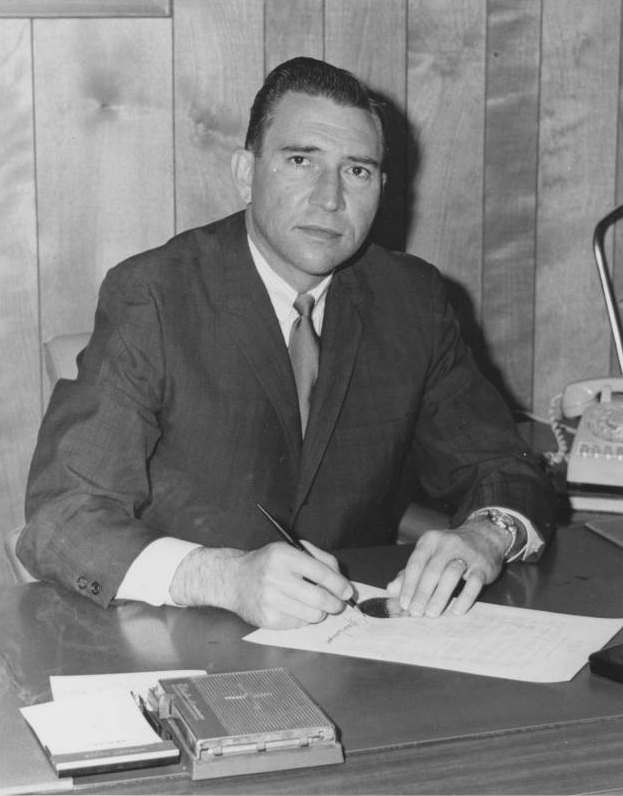

Sawyer, a Democrat elected in 1958, made the commission and board appointments in his first months as governor. He appointed former FBI agent Ray Abbaticchio Jr. as board chairman. The new regime decided to enforce the Gaming Control Act aggressively. Abbaticchio, dedicated and a straight shooter, took to heart Sawyer’s credo to “hang tough” in the chaos that they knew – but perhaps did not fully predict – would come next within the state.

The Gaming Commission, using the authority under the act to adopt new gaming regulations, took the important step of approving a strict policy aimed at casinos that accommodated known mobsters. Treating mobsters like high-rolling gamblers was a famously common occurrence, especially at the name resorts such as the Dunes, Sands, Stardust and Desert Inn on the Las Vegas Strip.

On February 20, 1960, the commission issued Regulation 5.010 stating that casino operators could lose their gaming licenses for “catering, assisting, employing or associating with, either socially or in business affairs, persons of notorious or unsavory reputation. …”

A new tool to fight organized crime materialized from the regulation, a tool not specifically mentioned in the Gaming Control Act. Sawyer and Abbaticchio interpreted the commission regulation as granting the control board “get tough” powers to make a preemptive strike against the intrusion of mobsters.

Abbaticchio, in consultation with Sawyer, quietly began compiling a list of names from among America’s organized crime bosses and underlings aimed at those known to stay in Las Vegas often enough to be noticed. The state would ban the selected hoods from Nevada casinos for life. Sawyer and the aggressive ex-FBI man viewed the anti-Mob effort as justified, legal as a gaming control device and necessary for the survival of Nevada gambling, ranked as the state’s top industry over mining and agriculture as of 1952. By 1959, revenue from gambling in Nevada grew to a record $206 million.

The board chairman compiled the names of 11 mobsters – eight of Italian ancestry – for the first tally. Caifano was one, as was his better-known Windy City boss, Sam Giancana, plus his Outfit colleagues Murray “The Camel” Humphreys and Tony “Joe Batters” Accardo. The others included Michael “Trigger Mike” Coppola of Miami; Kansas City mobsters Motel Grezebrenacy (aka Max Jaben) and brothers Carl and Nicholas Civella; Los Angeles boss Louis Tom Dragna and fellow L.A. mobsters Joseph “Wild Cowboy” Sica and John Louis “The Bat” Battaglia; and San Bernardino, California, vice boss (and Dragna crony) Robert L. “Bobby” Garcia.

State bureaucrats prepared the list in a haphazard manner – literally using plastic tape to affix copies of mug shots (with the names, descriptions and aliases of each man) onto pages of typing paper, then making Xerox copies.

They provided no name for the inventory, but the press would call it “the black book.” The book, birthed from the Gaming Control Act, would represent a new era for Nevada.

Before the book’s formal release, two of the wiseguys on the list got pinched. A sheriff’s deputy in Las Vegas on February 7 spotted Dragna and Battaglia in the Desert Inn’s Sky Room. The two hoods were in town with their wives. Dragna was dancing with his wife when the deputies arrested him and Battaglia on suspicion of vagrancy. The arrests made national news. Years later, Dragna would say that the 1960 detention left him “embarrassed and shocked.”

The sheriff’s department, interviewed at the time by the Associated Press, said officers took Dragna and Battaglia into custody “to keep Las Vegas from being an underworld rendezvous.” The jail released the men the next day. However, a Las Vegas police officer pulled over Battaglia, who drove from the jail, for speeding in a school zone, then arrested him on suspicion of vagrancy and grand theft, since the mobster could not prove he owned the car.

On March 29, 1960, Abbaticchio wrote letters to 13 major Las Vegas casinos about the list and enclosed copies of it. The Control Board tried to keep the list a secret, but the names leaked out to the press, and Abbaticchio confirmed the story to the media on April 4. That month, the board sent copies to the remaining casino licensees in Nevada.

On the copies, the board printed a warning to casino owners:

“The notoriety resulting from hoodlums visiting Nevada gaming establishments tends to discredit not only the gaming industry but our entire state as well. … In order to avoid the possibility of license revocation … your immediate cooperation is requested in preventing the presence in any licensed establishment of all ‘persons of notorious or unsavory reputation’ including the above individuals as well as those who subsequently may be added to the list.”

The commission made the list official on June 13, 1960. The Control Board now had stronger enforcement rights against Mob influence. The state intended the Black Book to list those considered dangerous to the gaming industry and who might tarnish the state’s desired reputation with the public of being free of Mob infiltration. Each person on the list was prohibited from entering a casino property – the gaming area, hotel, shops, lounges, showroom, restaurants and swimming pool. The state made the casinos responsible for making sure these known gangsters had to leave immediately or risk suspension or revocation of their licenses to do business.

The Reno Evening Gazette reported Abbaticchio having this to say about the Black Book in April 1960: “The wishes of the (control) board have been conveyed to the casino licensees. The manner in which they comply is their problem – and they are aware of it.”

The first hoodlum on the list to object was Battaglia, who came to Las Vegas on April 5 with his lawyer from Los Angeles. But he never did sue over being in the book.

Next was Dragna, who arrived in town weeks later with his lawyers in tow, intent on suing the state over his inclusion in the Black Book. He made a show of his disdain. He booked a room at the Dunes Hotel, then co-owned by Jake Gottlieb, an alleged associate of the Chicago Outfit and who, with partner Major Riddle, received a $4 million loan in 1958 from a Teamsters Union pension fund, thanks to Mob-connected union chief Jimmy Hoffa.

Dragna rebuffed requests by Dunes executives that he leave the premises. The mobster then partied on the Strip, attending live shows at the Sands, Tropicana and Stardust. All the while, a trio of gaming agents tailed him and informed executives at each casino about why they were there. Still, no one kicked Dragna out before he left town.

Control Board agents also kept on tabs on Caifano, who lived in Las Vegas for several years in the 1950s and owned a business and real estate in the area. The state knew that casinos on the Strip often afforded the alleged Mob hit man the royal treatment of food, drink and show comps. The agents and local cops started to lean on Caifano. He would describe that time while testifying in 1963, during the trial of his lawsuit against Nevada over the Black Book, in the federal courthouse in Las Vegas (today the site of the Mob Museum).

“After the Black Book came out in early 1960, I was always being followed everywhere, and everywhere I went I saw the same faces,” Caifano said. “We got to know each other pretty good. They were gaming officers, and police, also perhaps the FBI. It was that same everywhere I went.”

Confronted by agents for the first time, Caifano agreed to leave town. He soon returned on a supposed business trip. Things came to a head, famously, on October 28, 1960, after Caifano registered at the Tropicana Hotel. Caifano, with the singer Roberta Linn on his arm, defiantly entered a slew of Strip casinos – the Desert Inn, Flamingo, Last Frontier, Riviera, Sahara, Sands, Silver Slipper – and reportedly received warm welcomes from executives and staff.

Abbaticchio and a crew of 20 board agents took a plane from Reno and descended on the Strip. They made their presence known at the Tropicana, and in the casinos Caifano just visited, but in a way that would stoke controversy.

Intending to discomfit casino executives, they inspected playing cards and dice on the tables of the gambling halls Caifano entered. Abbaticchio himself seized some decks of cards, sealed them in envelopes, then had dealers, pit bosses and board agents sign the envelopes. The effort succeeded in alarming casino executives, and newspaper reporters soon appeared. Agents also required casino dealers to show their county work permits. In one instance, a table game pit boss refused to allow the card inspections and tried to block the agents from entering the pit.

Caifano ended his busy evening at the Desert Inn, operated by his friend, Moe Dalitz, former bootlegger and member of Cleveland’s Mayfield Road Gang but now a respected, and protected, member of the Las Vegas community.

He walked to the Desert Inn’s country club and watched a gaming board official argue with a hotel executive about who would toss Caifano out. The mobster went to a lounge for a drink, but when he ordered a second one, the waitress refused him service. He went to the bar but the tender declined his order. Then security guards and hotel executive Allard Rowen came to his table.

“These guys [gaming agents] are driving us crazy,” Caifano later quoted the Desert Inn people telling him. “They’ve picked up the cards and dice and we might lose our license if you don’t leave. I said, you guys are not going to throw me out. You had better not touch me. They said they were not going to. I got up and walked out.”

Caifano failed to mention that while exiting the Desert Inn, he ended up on the losing end of a fistfight with Frank Maggio, a photographer for the Las Vegas Sun newspaper.

Dragna and Caifano, in late 1960, separately filed suit in federal court, alleging that the sanctions imposed by the Black Book violated their civil rights. Dragna protested that he was simply a clothing manufacturer in Los Angeles who used Las Vegas to entertain clients and that his father, the retired former L.A. Mob boss Tom Dragna, lived in the town.

Caifano’s lawsuit, against some Desert Inn employees, Sawyer and 10 other state officials, asked for $150,000 in damages. He claimed that coercing him to leave the Desert Inn violated his rights under the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

In December 1960, with the two lawsuits pending, Sawyer and Abbaticchio were hammered by a surprising source – Nevada Attorney General Roger Foley. The A.G. went public with his displeasure about officials not informing him about the Black Book before its issuance. They should have run it past him first, Foley said, so that he could make sure it was constitutional. He blasted Sawyer for holding “secret meetings” and Abbaticchio for board “raids” on Las Vegas hotels and the confiscation of playing cards during live games after patrons had made wagers. He attacked the board for what he termed “Gestapo tactics” and the flaunting of “muscle in government.”

To dim the political fireworks, and reassure the gaming industry, Sawyer organized a conference meeting where state officials and gaming executives could discuss their differences. Foley agreed to appoint a special counsel to take on Caifano’s civil case against the state.

In June 1961, Sawyer announced that Abbaticchio, whose term would expire on July 1, would step down as board chairman, to be replaced by commission secretary Edward Olsen. Those in political circles expected Abbaticchio’s departure. He’d drawn the ire of a number of casino bigwigs. But he put out a statement saying he had no apologies to make.

“We have been fair, impartial and as helpful as we could and I believe the majority of the industry knows this,” he wrote in a press release.

The next test of Nevada’s Black Book, and its modern approach to gaming control, occurred in 1963, when the famous singer Frank Sinatra angrily refused to oust Black Book member Sam Giancana from staying at Sinatra’s Cal-Neva Club at Lake Tahoe. The board issued a complaint seeking revocation of Sinatra’s gaming license, its first attempt to remove a licensee for associating with a Black Book member. However, after discussing things with his lawyers and board officials, Sinatra decided he would rather sell his interest in the Cal-Neva, and his nine percent share of the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, worth a combined $3.5 million.

In 1966, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against Caifano in his civil case, and the Supreme Court declined to take it up.

Dragna lost his federal suit over the book in 1962. In 1966, a federal judge awarded him the token amount of $100 against the sheriff of Clark County and two deputies who arrested him for alleged vagrancy at the Desert Inn in 1960. Dragna had sought $10,500 in damages. The case had nothing to do with the Black Book.

Many new challenges, mistakes and legal disputes lay ahead for the board and commission. The reforms, regulations and the Black Book drawn from the Gaming Control Act finally put the syndicate, and negligent casino executives, on notice. The days of the pampered and tolerated celebrity gangster were numbered. Those who did come to town could suffer the bum’s rush from casinos, or perhaps a vagrancy charge.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org