The world’s top five Mob bosses

Kingpins oversee crime syndicates in Russia, Japan, Italy, Mexico and United States

There was a time when Mob bosses in the United States were household names, but not anymore.

Consider the FBI’s review of American-brand organized crime on its website. The “History of La Cosa Nostra” ends with the death of Genovese crime family boss Vincent “The Chin” Gigante in 2005. Gigante’s fame stretched back to the late 1950s, when his boss, Vito Genovese, ordered him to hit a rival, the Mob “Prime Minister” Frank Costello. Gigante’s shot only wounded Costello, who nonetheless retired after more than 30 years in the “business,” allowing Genovese to take over and rename Costello’s Luciano family after himself.

The Genovese family soon rose to the top of the LCN, and Vito kept running things even while serving time in a federal prison in Atlanta after his conviction for conspiracy to traffic narcotics in 1960. Gigante took over following Genovese’s death in the slammer in 1969. Gigante directed the crime group while faking mental illness, traipsing around in his bathrobe on the streets of New York’s Greenwich Village. But convictions for racketeering, murder conspiracy and obstruction of justice kept Gigante in U.S. custody from 1997 until he died in the very prison hospital where Gambino crime family boss John Gotti passed in 2002.

So, who’s the boss of anything today? Gigante’s demise represented the end of “celebrity” Mob bosses. No one seems to agree who the bosses of the LCN’s families are anymore, aside from speculation among pundits and the title of “acting boss” that federal prosecutors assign ad-hoc to family leaders from case to case.

Mob bosses outside the United States are somewhat more distinguishable. Part of the explanation could be that foreign bosses in general find it easier to hide from, or pay off, the authorities, even in the digital age. Some enjoy the political clout that money can buy in local and national governments, as in Russia, Italy, Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, Mexico and many countries in Central and South America. Still others are captured and jailed even before they reach infamy.

The list below of the world’s Mob bosses centers on five countries that are major hotbeds of organized crime activity and attempts to identify the leaders of the most significant syndicates in each one.

Russia: Semion Mogilevich

The grand don of world crime bosses has to be Semion Mogilevich of Russia. Multiple websites mention Mogilevich – 5 feet 6 inches tall, weighing about 300 pounds and a heavy smoker – as first among his mobster peers, if he has any. His nicknames include “Brainy Don” and “Boss of Bosses.” Some observers see him more as the Russian Mob’s top banker rather than a boss. He’s been on the FBI’s top 10 most wanted fugitives list since 2009, and the $100,000 reward for information leading to his arrest still stands. However, he is known to reside in Moscow, and Vladimir Putin’s Russia has no extradition treaty with the United States. Interpol also lists Mogilevich on its inventory of Europe’s most wanted.

Born in the Ukraine in 1946, Mogilevich joined the old Soviet Union’s Lyubertskaya crime clan in the early 1970s. After his apprenticeship, he started his own syndicate, the Solntsdevo gang. Of Jewish heritage, and once in possession of an Israeli passport, Mogilevich stole millions of dollars from Jews seeking to leave Russia for refuge in Israel in the 1980s. He used the proceeds to invest in both criminal and legitimate enterprises. In the 1990s, in Canada, he created YBM Magnex International, a supposed magnet manufacturing company based outside Philadelphia. But he never visited Philadelphia, and defrauded investors out of $150 million.

“Mogilevich has an economics degree and is deviously clever about manipulating funds – and investors,” according to the FBI’s official statement on him. “YBM, a public company incorporated in Canada, saw its stock price rise some 2,000 percent due to bogus financial records Mogilevich created, bribes to accountants, and lies told to Securities and Exchange (Commission) officials.”

Authorities from multiple countries charge the “Brainy Don” with some 40 criminal offenses from racketeering to wire fraud, conspiracy, aiding and betting, filing false documents with the SEC and money laundering. He’s also sought for questioning in alleged murder-for-hire schemes and dealing in drugs and firearms. Russian officials accused him in 1999 of using offshore companies to launder $500 million through the Bank of New York, but that was before the Putin era. In his native Ukraine, he’s suspected of taking part in a corrupt deal in 2005 with high-level politicians to import gas into the country from Russia and Central Asia. Yet he remains a free man in Russia, almost certainly thanks to protection from friends in high places.

Japan: Shigeharu Shirai

Japan’s equivalent to the Sicilian Mafia, the yakuza, is in the throes of a years-long decline. With the younger generation less interested in joining, new anti-gang laws discouraging graft and a waning of Japan’s historic tolerance of it, the group’s membership fell to 39,000 in 2016 from about 63,000 four years earlier. The 103-year-old Yamaguchi-gumi gang, based in the city of Kobe, remains the leading crime clique of the yakuza’s four families. The “gumi” family split up in 2015, creating a faction, the Kobe Yamaguchi-gumi. Then in 2017, another splinter group, named the Ninkyo Yamaguchi-gumi, came about after its leader, Kunio Inoue, clashed with “gumi” boss Kenichi Shinoda.

The division did not seem to help the Kobe gang. Later in 2017, two Kobe “gumi” guys – one 52, the other 59 – were busted at a shopping mall while trying to steal $700 worth of groceries, including rice, a watermelon and an eel. One of the aging gangsters confessed to police that members must resort to shoplifting because “the group is so poor.” This from a transnational crime group said to earn billions a year from drug trafficking, prostitution, gambling and other rackets within its ranks.

Who is the latest yakuza boss? If that means the most infamous (read: most publicized), it would have to be Shigeharu Shirai. A 74-year-old Yamaguchi-gumi leader, Shirai bolted from Japan to Thailand in 2005 and remained on the lam with an expired visa until his arrest this past January.

Shirai’s very-yakuza colorful gang tattoos gave him away, via social media. Someone snapped photos of him playing checkers on a sidewalk with his shirt off, exposing multihued floral tattoos on his chest, upper arms and back. After the photos went viral, Japanese police notified Thai authorities that Shirai was a wanted suspect in a gangland slaying from 2003. Thai police arrested Shirai, who denied the murder allegation. Officers released damning pictures of his hands, revealing another yakuza pedigree – his left pinkie finger severed below the first knuckle, a common form of punishment for gangdom wrongdoing.

Italy: Matteo Messina Denaro

The Mafia and the seeds of modern organized crime started in the mid-19th century in Italy and its island state of Sicily. The Mafia remains there today, a virtually unbeatable if diminished foe for Italian law enforcement and society.

“You are never going to win victory over the Mafia, just as you can never totally defeat evil.” Sicily’s anti-Mob governor Roserio Crocetta told the Reuters news service last year.

But the standing of the Sicilian Mafia has been receding for quite some time, ever since the assassinations of two top anti-Mafia crusading magistrates, Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, in separate bombings back in 1992. Similar to the public outcry in America from the 1929 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago, where Mob gunmen slaughtered seven men inside a garage, the 1992 killings of Falcone and Borsellino in Sicily inspired a nationwide crusade against organized crime. Anti-Mafia reform laws passed in Italy since then have prompted many raids by military and state police and hundreds of arrests. One Mafiosi, captured in 1993, was the vicious “boss of bosses” in Palermo, Salvatore “Toto” Riina. The courts imposed 26 life terms on Riina for directing the 1992 killings of Falcone and Borsellino and his guilt in more than 100 murders as a Mafia boss. He lived a long life. The Sicilian-born Riina died in an Italian prison in November 2017, a day after his 87th birthday.

Some Mafiosi in Palermo have lately joined with a Nigerian migrant gang, the Vikings. The gang forces female Nigerian migrants into prostitution to pay off large debts they incur to emigrate. The Mafia is also attempting a comeback by expanding beyond public works fraud and extorting “pizzo” fees from small businesses to trading in illegal hashish imported from northern Africa.

Meanwhile, the ’Ndrangheta of Calabria currently reigns not only as Europe’s major trafficker in cocaine, but as Italy’s most influential Mob, ahead of the Sicilian Mafia, the Camorra of Naples and Sacra Corona Unita of Bari. In Germany, the ’Ndrangheta operates hotels and bars and uses the European port cities of Rotterdam and Antwerp to smuggle in the South American-made cocaine it traffics there.

Nevertheless, the ’Ndrangheta’s leadership, some of whom have been in hiding for many years, have suffered major setbacks at the hands of police. In June 2017, officers of the Italian Carabinieri military entered a home in a small village in Calabria and found drug boss Giuseppi “U Capra” Giorgi. The boss quietly concealed himself for several hours behind his fireplace until officers heard him move. It was a long time coming. Police had searched for the 56-year-old Giorgi for 23 years, since a judge sentenced him to 28 years in prison for drug trafficking in 1994. Police also believe he dealt in firearms and unlawfully disposed of hazardous waste by sinking a loaded ship off the coast of Italy.

This past April, state police in Calabria nabbed another notorious ’Ndrangheta boss, Giuseppe Pelle, wanted for Mafia association and extortion since 2016. Officers found Pelle, the 57-year-old head of the Pelle-Vottari gang and member of the ’Ndrangheta ruling council, in an isolated house, sleeping on a couch, dressed as if ready to flee.

Today, Italy’s biggest Mob boss arguably could be another longtime fugitive, Matteo Messina “Diabolik” Denaro, a 56-year-old kingpin and “most wanted” outlaw since he disappeared in 1993. Denaro, who cleverly evades justice in various hideouts, is a suspect in dozens of murders. Still, police may be getting closer to him. On April 19, 2018, they arrested Denaro’s two brothers-in-law, who allegedly ran his criminal rackets for him in Trapani, Sicily, along with 19 other associates.

With the death of Riina, speculation about his successor has turned to Denaro, whose Trapani crew continues to make a good living in Sicily via extortion, fraud and skimming off public works contracts.

Mexico: Nemesio Oseguara-Cervantes

For more than a dozen years, warring drug cartels fighting over control of multibillion-dollar rackets, from drug and human trafficking to extortion, kidnapping, oil theft and illegal mining, have thrown Mexico into chaos. Since 2006, more than 200,000 people have been murdered or declared missing, even with government-ordered crackdowns by the Mexican military. Efforts to limit the power of the cartels frequently fail as criminal gangs simply make adjustments. Bribery and corruption by organized crime is widespread in Mexico, extending from small-town police and politicians to officials in the federal government.

Lately, Mexican federal law enforcement has declared the Jalisco New Generation cartel as the most powerful of the country’s transnational crime syndicates (others include the Sinaloa, Los Zetas, Gulf, Juarez, Tijuana and Beltran-Leyva). Jalisco New Generation started in 2010 when members quit serving as the armed unit of the Sinaloa cartel to create their own drug trafficking band.

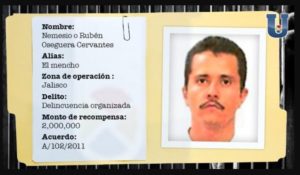

The best candidate for Mexican cartel boss of the moment is Jalisco’s reputed boss, Nemesio Oseguara-Cervantes, also known as “El Mencho.” Convicted of conspiracy to distribute heroin in California in 1994, he was released three years later and returned to Mexico to take up drug trafficking. Born in 1966, “El Mencho” is now among the DEA’s most wanted international drug traffickers under the U.S. Kingpin Act, passed by Congress in 2000 to lodge harsh criminal and civil fines against high-level drug traffickers.

Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel, once the biggest and most dominant, still exists as a top narcotics supplier despite the loss of its world-famous boss, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, to arrest in Mexico in 2016 and detention in the United States since 2017. El Chapo is on trial in federal court in Brooklyn, New York, for a daunting list of murder, racketeering and other felony charges, and is almost sure to end up serving a life sentence.

After his arrest, Sinaloa members split, with some loyal to El Chapo’s sons Ivan Archivaldo and Jesus Alfredo “Alfredillo” Guzman-Salazar. Also regarded as an influential player in the mix is Aureliano Guzman, El Chapo’s brother.

Two others in the top echelon of the Sinaloa cartel, Ruben Caro-Quintero, one-time head of the since-disbanded Guadalajara Cartel, and Ismael “Mayo” Zambada-Garcia, are fugitives wanted by U.S. authorities for drug trafficking, conspiracy and racketeering. Caro-Quintero is also on the radar for the kidnapping and murder of DEA agent Enrique Camarena in 1985.

As it goes, Caro-Quintero might be a contender with Oseguara-Cervantes for top boss of Mexican organized crime. American authorities believe Caro-Quintero directs activities of the Sinaloa drug syndicate and his Caro-Quintero trafficking organization in the Badiraguato region of the Sinaloa state. Furthermore, the U.S. State Department is still offering a $20 million reward for arrest information on the 65-year-old Caro-Quintero.

The State Department also has proffered a $5 million reward for information leading to Zambada-Garcia’s arrest. He is known to use airplanes, trucks and cars to transport tons of cocaine from Colombia into Mexico, plus tons of marijuana and kilos of heroin, for trafficking into the United States.

United States: Matthew Madonna

When FBI agents arrested 19 alleged leaders and members of the Lucchese crime family in New York and New Jersey in May 2017, the news media played up its association with a pop culture narrative of America organized crime. The Lucchese retained the link – or “the source of inspiration” as the British paper The Guardian put it – with the plot of the 1990 mobster film Goodfellas. The news stories included references to some of the nicknames of those arrested, such as “Paulie Roast Beef” and “Joey Glasses.”

It was a good bust by the Justice Department, and as with previous disruptions of America’s La Cosa Nostra, a federal prosecutor used it as proof that the LCN still operates, even decades after its heyday from the 1920s to the 1990s.

“As today’s charges demonstrate, La Cosa Nostra remains alive and active in New York City, but so does our commitment to eradicate the Mob’s parasitic presence,” Acting U.S. Attorney Joon H. Kim stated in the news release. “The defendants allegedly used violence and threats of violence, as the Mob always has, to make illegal money, to enforce discipline in the ranks, and to silence witnesses. The Mob members and associates charged today will answer for their alleged misdeeds in a court of law.”

The remnants of the LCN still run crime operations in several sections of the New York-New Jersey area. Instead of only five crime families, the feds cite six – the Genovese, Gambino, Lucchese. Columbo and Bonanno of New York and the Decavalcante of New Jersey. The “administration,” or management structure, of each family consists of a boss, underboss and consigliere, followed by the usual underlings: capos, soldiers and associates. The feds cut and paste these facts into each of their indictments of LCN members.

Last January, the “acting boss” of the Bonanno crime family, Joseph Cammarano Jr., 59, his consigliere John Zancocchio, 61, eight Bonanno captains and soldiers in their crew, one Genovese family soldier and a Lucchese soldier were indicted on alleged racketeering conspiracy charges that included extortion and assault with serious injury. Each of the 10 defendants could receive 20 years to life per count of racketeering.

But who are the LCN bosses these days? The prominent media “stars” are long gone.

Today, while there certainly are many intelligent criminals, there is no surplus of the kind of talent there was among those legendary bad men – Al Capone, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Costello, Genovese, et al – born in the late 19th or early 20th century in Sicily or Italy or as first- or second-generation American immigrants. Also, in the digital age, it’s getting harder to maintain a low profile. Plus, who wants to do “our thing” anymore in the first place? Not many. The smart kids of one-time LCN mobsters tend to go the legitimate, professional route.

Among the “bosses” or key figures in American LCN, there isn’t anyone consistently described in the headlines of the New York newspapers as the “Racket King,” as Vito Genovese was back in the day.

The traditional LCN families do exist in some fashion, and high-profile federal indictments and arrests of them still come and go in New York. And though reduced in scope and in political influence, they remain as villainous as ever.

Let’s give the American LCN boss of the year award to one of the old guys caught up in the criminal actions alleged in the Lucchese bust: Matthew Madonna, now 82 years old, described by police as the Lucchese “street boss.” His underboss, a worse character, is Steven “Wonder Boy” Crea Sr., 70. Their 82-year-old consiglieri is Joseph DiNapoli, and then there’s Crea’s son, Steven, who’s 46. All face life in prison from a list of felony allegations related to racketeering from 2000 to 2017. The charges, based on grand jury indictments, include one murder, two attempted murders, injurious assaults, witness intimidation, trafficking in illegal drugs (cocaine, heroin, prescription opiates and marijuana), robbery, wire and mail fraud, illegal gambling and money laundering and selling untaxed cigarettes.

Madonna, Crea Sr. and Crea Jr. and two others, Christopher Londonio, 44, and Terrance Caldwell, 60, are charged with conspiring to murder Michael Meldish, a 62-year-old veteran hit man found shot in the head in his car in the Bronx in November 2013. Meldish, believed responsible for at least 10 Mob slayings, was a former member of New York’s Purple Gang, a 1980s drug-pushing ring out of the Bronx and Harlem once associated with members of the Lucchese, Genovese and Bonanno families.

Meanwhile, the feds have charged Crea Sr. with fraud in trying to enrich himself from a $25 million expansion of New York Hospital.

In May, federal prosecutors announced they would not seek the death penalty for Madonna, Crea Sr., Crea Jr., Londonio or Caldwell. However, it’s safe to say the LCN is not yet on life support.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org