Forty years ago, Jimmy “The Weasel” Fratianno turned on his Mob family

Cleveland/L.A. Mafia boss became high-profile informant and witness for the government

Some mobsters left their legacy by the gun, some by the knife, but Jimmy “the Weasel” Fratianno is best known today for his voice. He was no operatic tenor, but when he started talking about the Mob’s business, it was sweeter music to the FBI than any Mario Lanza aria.

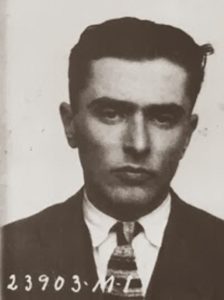

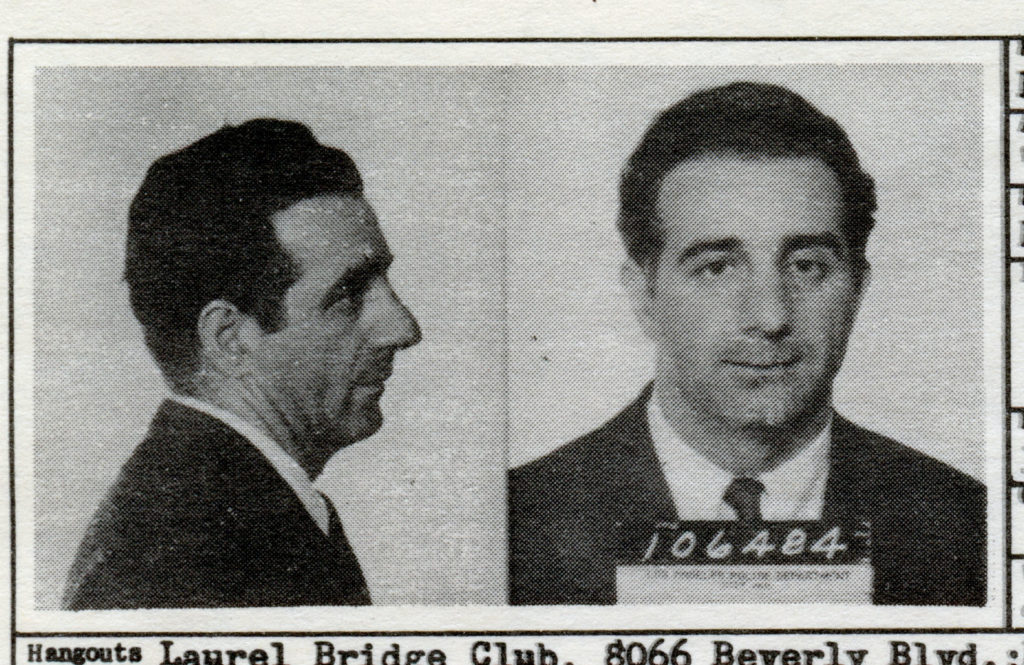

Fratianno, born in Naples, Italy, in 1913, emigrated to the United States as an infant. He and his mother joined his father in Cleveland’s Little Italy, where he got an early education in crime. Fratianno gained his nickname from running “like a weasel” from a pursuing police officer, though, like Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, he was seldom called it to his face. He began working in gambling at age 14 under the aegis of Johnny Martin, and within three years was Martin’s equal partner in his operation near the Fisher Body auto plant.

Fratianno spent his teen years climbing the criminal ladder in Cleveland, but really came into his own in Los Angeles, where he moved in 1946. An early ally of Johnny Rosselli, Fratianno’s star rose quickly. He became a made man (in a ceremony similar to the one depicted on the Mob Museum’s second floor) in 1947. While he made himself a new life in Los Angeles, his Cleveland roots gave him contacts that would long benefit him, in both the Teamsters Union and with Moe Dalitz and his associates.

With those connections, it’s natural that Fratianno became involved with Las Vegas. He knew Siegel and visited him at the Flamingo shortly before his June 1947 murder. In 1953, Fratianno was a self-confessed accomplice in the murder of “Russian” Louie Strauss, who had unwisely attempted to extort Benny Binion. But there was a deeper connection. His allies Dalitz and the Teamsters both, by the 1960s had substantial interests there, and, through his position in Los Angeles (Fratianno was, for a time, at the top of the city’s underworld hierarchy) and his connections nationally, was privy to the many skimming operations that funneled money to Mob bosses in Kansas City, Chicago and elsewhere.

In 1965, Fratianno attempted to gain control of the Tally Ho, a Strip hotel that was in the process of gaining a casino and becoming the Aladdin. He went all-in on Las Vegas, buying a home at 336 Mallard Street (just off Jones Boulevard and Alta Drive) and even flying his parents out for a visit. His dreams of being a casino mogul died, however, when gambler Eddie Nealis, who was fronting the deal, ran into licensing and financial troubles.

In 1973, after finishing a stint in Chino prison, Fratianno began cooperating with the FBI. Initially, he gave them only information he thought was worthless or that could compromise his enemies. But as inter- and intra-family rivalries made his position more precarious, in December 1977 – 40 years ago this month – he made the decision to break with the Mob. He joined the federal Witness Protection Program and testified against his former “family,” breaking the vow he had made 26 years earlier.

In 1973, after finishing a stint in Chino prison, Fratianno began cooperating with the FBI. Initially, he gave them only information he thought was worthless or that could compromise his enemies. But as inter- and intra-family rivalries made his position more precarious, in December 1977 – 40 years ago this month – he made the decision to break with the Mob. He joined the federal Witness Protection Program and testified against his former “family,” breaking the vow he had made 26 years earlier.

As a highly placed underworld figure, Fratianno was the most valuable informant the FBI had turned to date. He was voluble about Rosselli’s role in selling the Desert Inn to Howard Hughes and his part in the CIA’s Operation Mongoose, the failed attempt to assassinate Cuban leader Fidel Castro that saw the Mob team up with the federal government, even as Bobby Kennedy was fighting a well-publicized “war” on organized crime in the early 1960s.

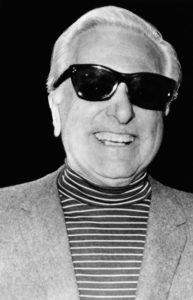

Fratianno made the most out of his new career as a talker, collaborating on two books (The Last Mafioso and Vengeance Is Mine). Both books were ghost-written and he would say he never read either. He did, however, make the rounds of the talk show circuit, and he claimed to be keeping one step ahead of a $100,000 contract on his life.

In the end, Fratianno got a privilege denied to his victims and many of his friends, such as Rosselli: He died peacefully at age 80, suffering from Alzheimer’s disease.

David G. Schwartz, author of several books on Las Vegas gaming history, is director of the Center for Gaming Research and teaches history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org