The life and crimes of a Sinaloa sicario

Mexican cartel hitman known as ‘El Mano Negra’ confessed to dozens of murders 10 years ago

Ten years ago, the confessions of a California-based hitman revealed new information on decades-old unsolved cases and offered a glimpse into the shadowy domestic operations of Mexican drug cartels.

In the summer of 2013, the national media began to report on a developing story from Lawrence County, Alabama. The news of the potential capture of a serial killer caught the attention of many, with headlines and television reports spreading the information, albeit limited and brief in scope. The reports began when local officials announced a surprising confession from a man in custody on a murder charge.

Jose Manuel Martinez, a charismatic, 50-year-old father and grandfather from California’s Central Valley, was apprehended in Arizona on May 17, 2013, by Border Patrol agents on an Alabama murder warrant.

Martinez was extradited to face charges for the murder on March 4 that year of Jose Ruiz in Danville, Alabama. He confessed to the killing, saying the crime was a matter of honor rather than business, reportedly due to disparaging remarks Ruiz made about his daughter.

He also claimed responsibility for more than 30 unsolved murders across the country as a freelance sicario.

A sicario is born

Born in 1962 in Fresno, California, Martinez had a unique upbringing that exposed him to contrasting worlds. He spent part of his early childhood in Mexico but returned to California as a preteen. There he witnessed the daily struggles of hardworking migrant farm workers who strived to make ends meet. He was also surrounded by the secretive and ever-present influence of organized crime, including his own stepfather, a heroin trafficking ringleader convicted in 1977 and sent to Lompoc prison for several years.

Martinez’s formative years were marred by a devastating loss when his older sister was raped and murdered in 1978. That family tragedy ignited a deep desire for vengeance, which led him down a dark path. The 16-year-old Martinez hunted down and murdered the three men he believed were responsible for his sister’s death and buried them “on top of each other” in a shallow grave. Martinez had discovered a vocation from which there was no turning back.

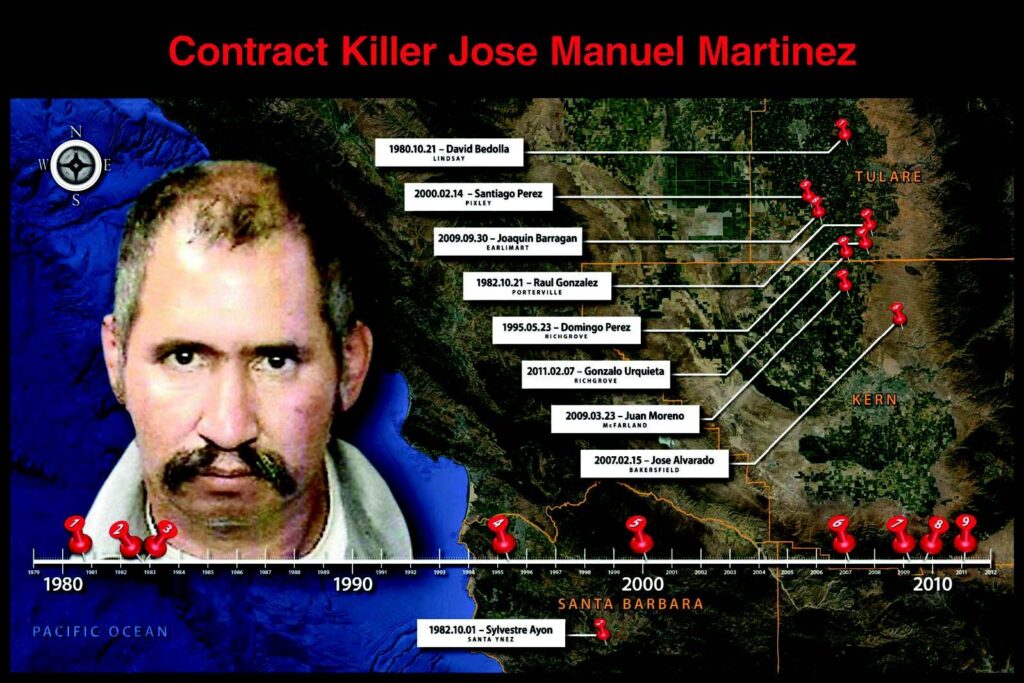

On October 21, 1980, Martinez carried out his first professional murder contract by killing 23-year-old David Bedolla in a drive-by shooting.

The black hand

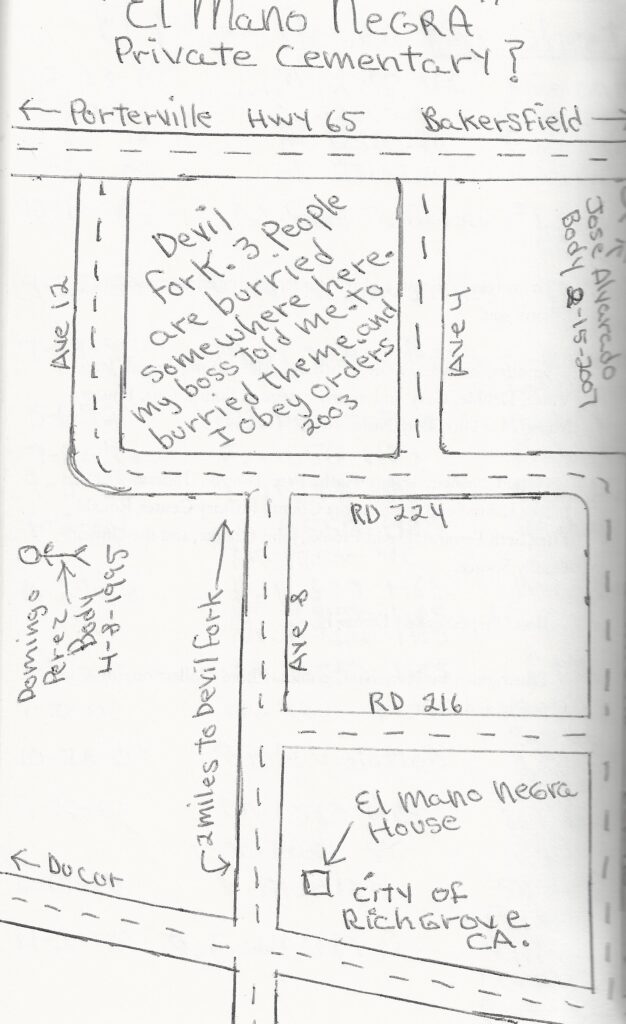

Although the headlines about the alleged cartel serial killer eventually faded, law enforcement continued to explore Martinez’s claims in hopes the discoveries would bring closure to cold cases. While awaiting trial in Alabama, investigators periodically interviewed him, and many of Martinez’s claims held true. He provided intricate details that only the perpetrator could have known, such as victim descriptions and the types of spent ammunition left at some scenes. He also drew maps and diagrams of the crime scenes. This was productive information regarding unsolved murders in Martinez’s California hometown and neighboring counties.

A 2013 summary report from the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office divulged details about the sicario’s method and nickname:

“For Martinez’s contract killings, he would usually conduct surveillance on the target for a few days. One particular job Martinez spent one week doing surveillance, establishing the target’s pattern. Martinez usually has a bodyguard with him. The client supplies the firearm for the job; this way he never uses the same weapon for different targets. Martinez practices his shooting regularly. When he was a young man, he shot guns so much an old man called him ‘the black hand’ because of the gunpowder that was darkening his skin on his shooting hand. This became more relevant after establishing his career, with an aka of El Mano Negra.”

When he was arrested, Martinez had a considerable rap sheet and several stints in jail. Most were drug and human trafficking charges and probation violations, but no major violent crime charges. He somehow remained largely off the radar and was effectively a phantom sicario for more than three decades. From an economic perspective, his work yielded the greatest results when he managed to collect debts from his victims, from which he earned a generous percentage. In 2018 he wrote: “Killing people is not where the money is; collecting drug that is where the money is.”

Killing for the cartel

Martinez was cooperative to a certain extent with investigators. However, he staunchly declined to reveal the identities of his partners, employers or the locations of buried bodies. When Tulare County detectives tried to pry information from him, he told them bluntly, “I’m not your teacher.”

Furthermore, tensions escalated whenever drug cartels were mentioned, as demonstrated in a 2014 interview:

DETECTIVE: “Let me ask you this: Do you have connections and information on the cartels?”

MARTINEZ: (Laughs)

DETECTIVE: “No, hear me out before and whether you do or not, just hear me out.”

The conversation took a few different turns as the detective revisited other unsolved cases from Tulare County. Martinez later denied them once more:

MARTINEZ: “Uh-huh, I don’t talk about cartels.”

DETECTIVE: “All right. Well, that’s your choice then. I can’t force you to.”

MARTINEZ: “Yeah.”

DETECTIVE: “But I’m just throwing that offer out there. I’ve already spoken to people at the federal level, and they would love to come and talk to you, but they’re not going to waste their time coming here.”

MARTINEZ: “I understand. Yeah.”

Martinez’s affiliation with the cartel gradually became apparent during numerous interviews and statements, even though he was hesitant to disclose precise information. When asked about Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, Martinez vaguely responded, “I cannot give — yes, I know El Chapo, something like that.” He gave subtle hints at his Sinaloa connections in discussions with investigators from Alabama and Florida, as summarized in police reports.

What isn’t so vague is the Sinaloa Cartel’s notoriety. The loosely associated drug traffickers of Sinaloa, Mexico, saw more cohesion by the early 1980s. Their leaders, based in Guadalajara, earned international infamy in 1985 after the brutal murder of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena. It was this organization, later known collectively as the Sinaloa Cartel, that had tentacles reaching into California by the 1960s and ’70s. Martinez claims to have done freelance work, but his role in the United States was predominately to carry out enforcement and collection for the Sinaloa Cartel network.

His unpublished memoir provides more hints about his affiliation with El Chapo and the Sinaloa Cartel. “The state of Sinaloa had lost the best hitman,” he wrote about his 2013 arrest. Martinez also recounted a story about his superior, referred to only as “Mr. X,” hosting with “special friend”: “At 1:30 pm my compadre arrived … with El Chapo. They talked for almost an hour. El Chapo had three other men with him. Keep in mind – back in 1991 El Chapo wasn’t famous. He was very rich, but not famous yet. He became famous after escaping Puente Grande prison in Mexico.”

It’s not business, it’s personal

“I left dead people everywhere, rivers, lakes, trucks, roads, orange fields, grape fields, you name it,” Martinez wrote in a 2018 postcard to the author. El Mano Negra’s bloody reign began with the revenge killing of his sister’s murderers and concluded with another act of retaliation in the Ruiz case. Most of the murders in between were sanctioned hits or contract jobs.

The Alabama trial reached a resolution when Martinez pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 50 years in prison in June 2014. California authorities extradited Martinez soon after.

They formally charged him with nine counts of first-degree murder and one count of attempted murder. These charges also encompassed “special circumstances,” including lying in wait, kidnapping and murder for financial gain. Because the murders occurred in three different counties, officials agreed to consolidate them into a single trial in Tulare.

In September 2014, U.S. marshals moved Martinez to the Tulare County Adult Pre-Trial Facility in Visalia for arraignment. After waiting more than a year for the trial to start, he received 10 consecutive life sentences. Authorities in Florida announced their intent to pursue the death penalty and initiated the extradition process for Martinez for the double homicide of Javier Huerta and Gustavo Olivares-Rivas in 2006. The trial began and ended in June 2019 with Martinez’s fate in the jury’s hands. The panel opted for life in prison, saving Martinez from death row. He is currently serving his time in a U.S. penitentiary in California.

If all his claims are true, then there remain at least 23 unresolved murder cases.

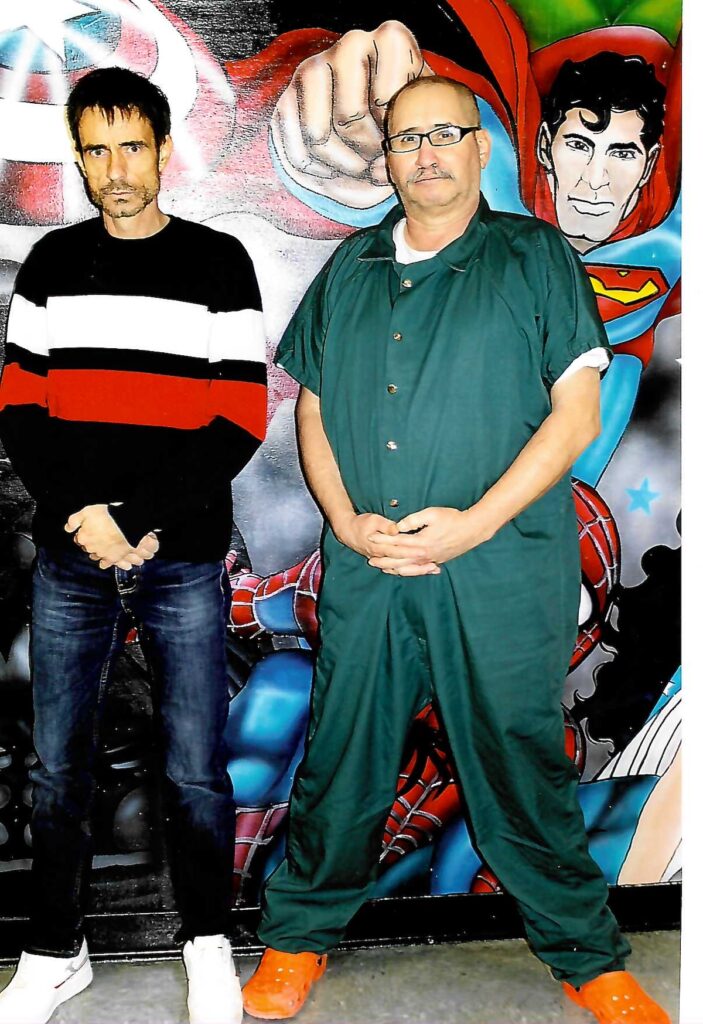

Author’s note: Since 2018, I have maintained communication with Jose Manuel Martinez via mail, phone, video visitation and in-person meetings, and collected materials related to his cases. In late 2024, Gorilla Convict Publications will release his handwritten memoir, accompanied by an extensive collection of investigation materials, photographs and diagrams. This publication will mark the first time these materials have been made available to the public.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad and LUCKY, a gangster graphic novel.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org