Battle for Las Vegas

The Mob Comes to Town

The Chicago Outfit Joins the Party

Lefty and Tony Come Aboard

State Resists Rosenthal Licensing

Law Enforcement Ramps Up

Mob on the Run

The Aftermath

The Chicago Outfit's Last Big Swindle in Las Vegas

How local, state and federal law enforcement banded together to root out the Mob

Details

THE MOB COMES TO TOWN

Mobsters started moving to Las Vegas in the 1940s. They flocked to the small desert city to escape troubles in their hometowns, to take advantage of the dramatic wartime growth of Las Vegas, and to run casinos without having to constantly look over their shoulders.

Details

The first wave of organized crime figures migrated to Las Vegas from Southern California, including Guy McAfee, Tutor Scherer, Farmer Page and Marion Hicks.

Details

They were fleeing a political reform movement led by California Attorney General Earl Warren, who took on the gambling ships parked off the coast, and Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron, who cracked down on vice in the city.

Details

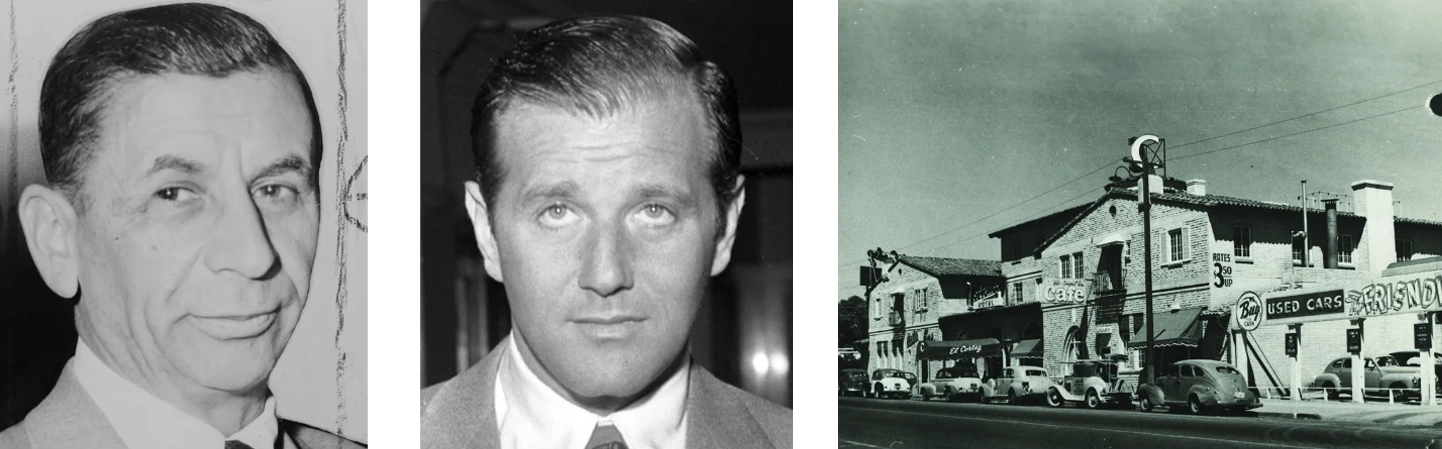

In 1945, mobsters from New York, including Meyer Lansky and Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, planted their flag in Las Vegas by purchasing El Cortez hotel-casino on Fremont Street.

Details

A year later, Lansky and Siegel took a bigger step when they partnered with Los Angeles nightclub owner Billy Wilkerson in the development of the Flamingo Hotel on what would become the Las Vegas Strip. Siegel eventually pushed Wilkerson out and took full control of the project.

Details

The Flamingo’s success sparked a casino building boom in Las Vegas in the 1950s, and mobsters from all over the country were involved with many of the resorts. Las Vegas was regarded as an “open city,” meaning there were no territorial restrictions on who could invest in the city.

Details

THE CHICAGO OUTFIT JOINS THE PARTY

The Chicago Outfit’s first foray into Las Vegas came at the Riviera Hotel in 1955. Although the Riviera was built by Mob-connected investors from Miami, it soon came under the Chicago Mob’s control.

Details

Chicago placed Gus Greenbaum in charge, and he operated the Riviera successfully until he and his wife were murdered in Phoenix in 1958.

Details

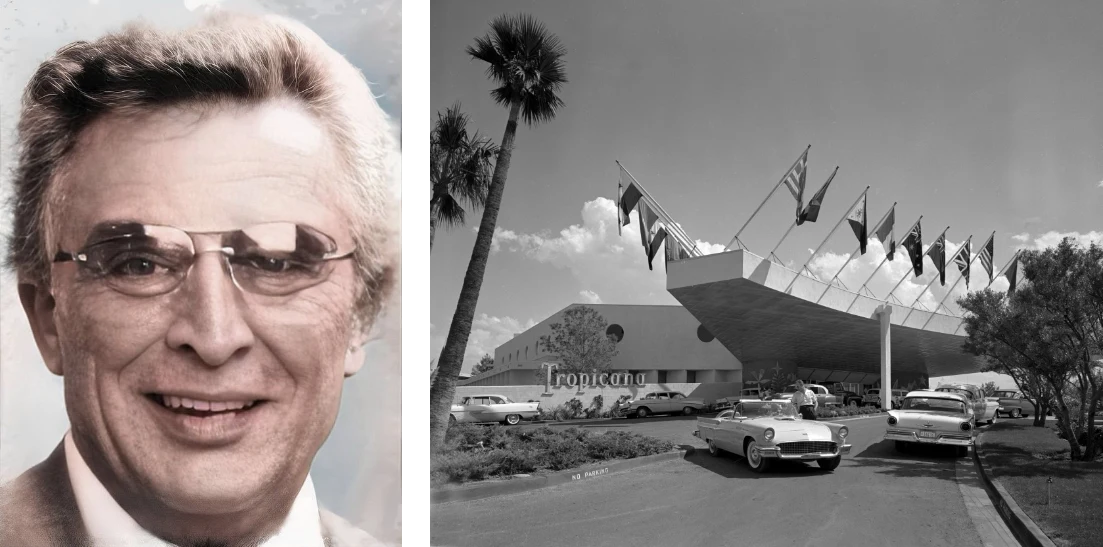

Chicago mobsters lost control of the Riviera in the late 1960s. Their grand return to Las Vegas occurred in the following decade after San Diego real estate investor Allen Glick purchased the Stardust, Hacienda, Fremont and Marina hotel-casinos. Glick’s casino company was the Argent Corporation.

Details

In order to purchase and upgrade the Las Vegas properties, Glick obtained a $63 million loan from the Teamsters Union’s Central States Pension Fund. Teamsters President Jimmy Hoffa created the pension fund in 1955, and he used it to finance Mob-connected casino projects in Las Vegas.

Details

After Hoffa went to prison in 1967, the pension fund came under the supervision of Allen Dorfman, who was closely connected to the Chicago Mob. As a result, Glick’s acceptance of the Teamsters loan meant the Mob effectively controlled his properties.

Details

LEFTY AND TONY COME ABOARD

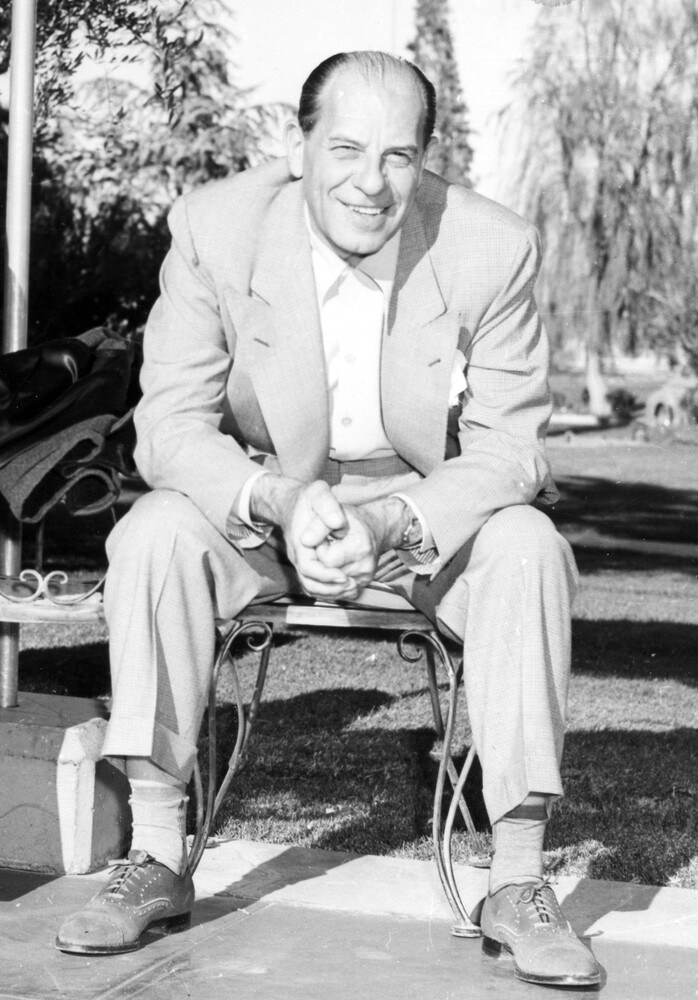

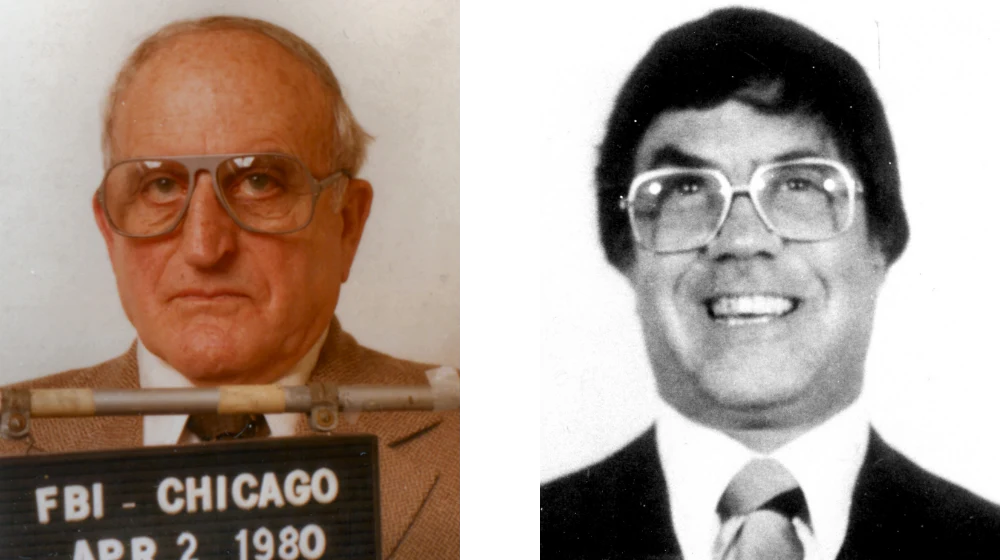

Chicago crime bosses Tony Accardo and Joey Aiuppa installed a notorious sports bettor named Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal to run Glick’s casinos. Rosenthal’s primary duty was to ensure that the skim — a portion of the casino’s revenue removed before any official tallies — occurred without any hiccups.

The skim from the Argent casinos was divided among the Mafia families in Chicago, Kansas City, Milwaukee and Cleveland.

Details

The Mob skimmed from the casinos in multiple ways. Stardust slot manager Jay Vandermark orchestrated one operation using manipulated scales to count coins. That scheme fleeced an estimated $7 million to $15 million between 1974 and 1976.

When state gaming investigators discovered what Vandermark was doing, he disappeared, a suspected murder victim to ensure he did not speak to authorities. His body has never been found.

Details

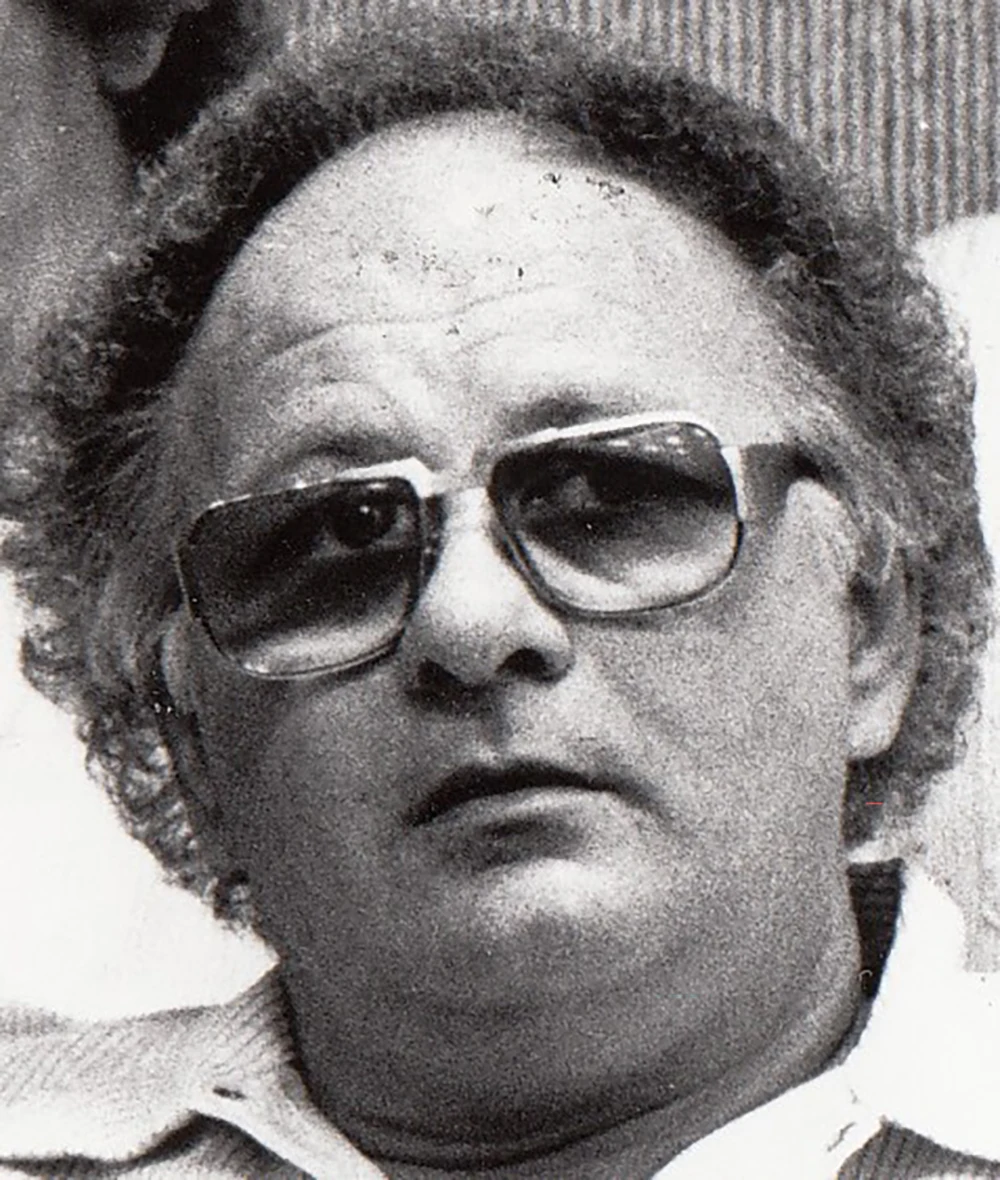

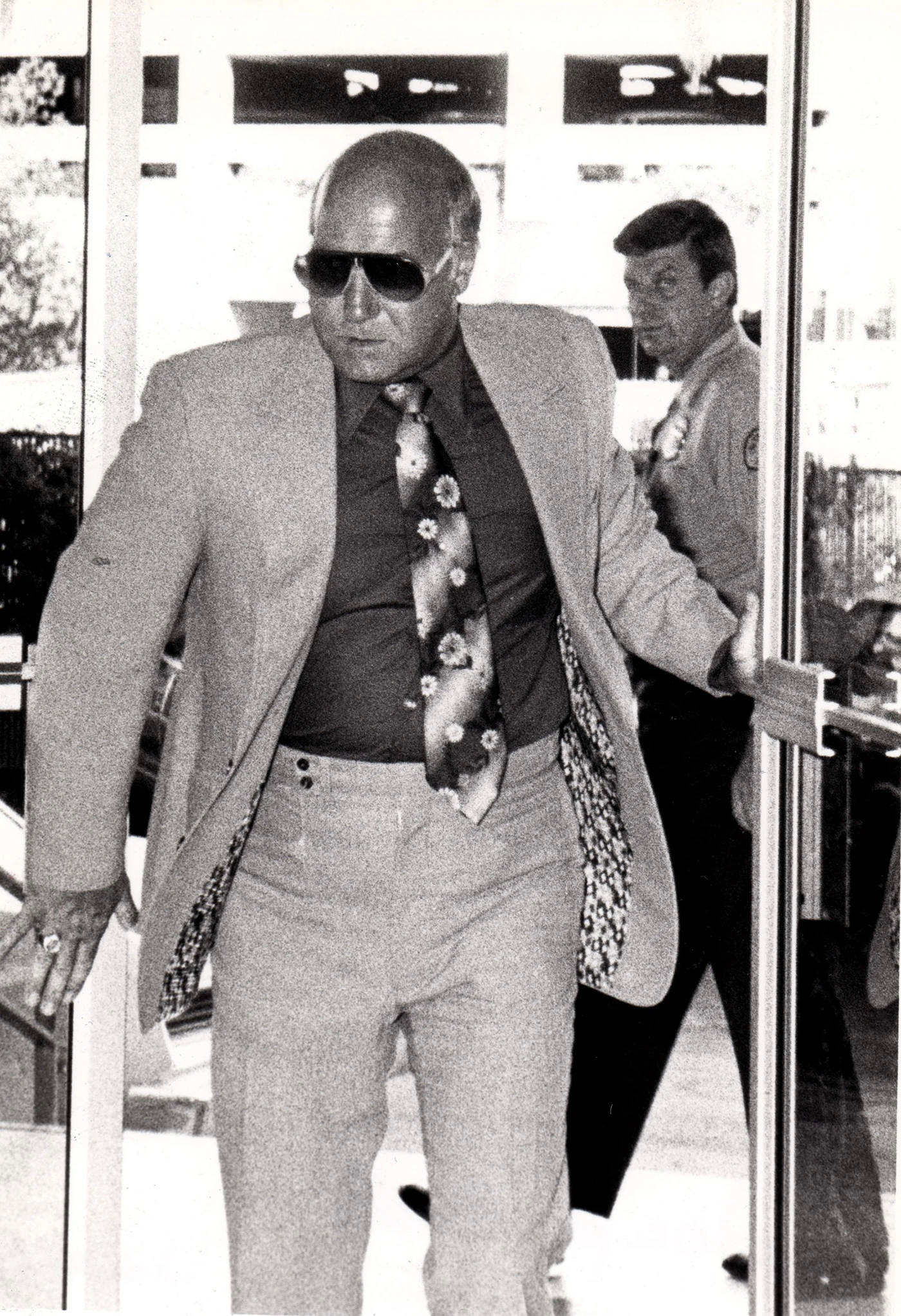

Rosenthal was the Chicago Outfit’s man on the inside. Its outside man was Tony Spilotro, whose job was to address any problems that might interfere with the skim. Spilotro did that, as well as running an array of traditional criminal rackets in Las Vegas, including robberies, burglaries, bookmaking and loansharking.

Details

Spilotro was widely regarded as a ruthless killer, a reputation he earned on the streets of Chicago before he came to Las Vegas. In 1962, Spilotro allegedly murdered Billy McCarthy and Jimmy Miraglia after that duo killed a couple of Outfit-connected men in a bar. The so-called “M&M murders” include the grim detail that Spilotro put McCarthy’s head in a vise and squeezed it until his eye popped out.

Details

After Spilotro moved to Las Vegas in 1971, he was suspected in a number of murders, including those of William “Red” Klim in 1973, Marty Buccieri in 1975 and Tamara Rand in 1975. Rand had invested in Glick’s casinos. When she filed a lawsuit against Glick for breach of contract, she was murdered in her San Diego home. Spilotro never was prosecuted for any of these murders.

Details

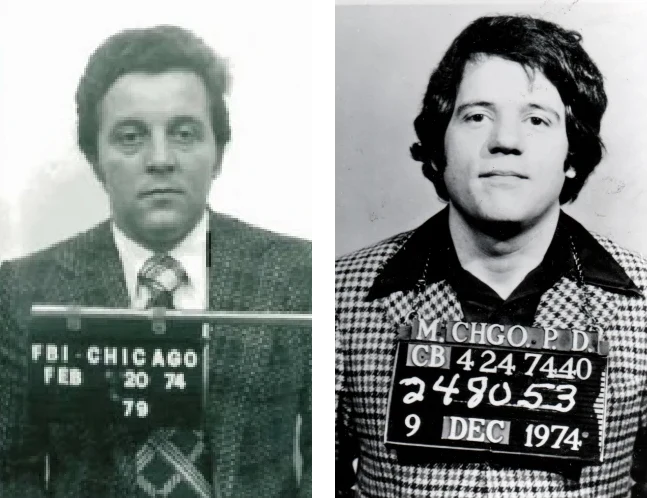

Spilotro also led a burglary crew that gained the nickname the “Hole in the Wall Gang,” because it often punched holes in walls and roofs to avoid security systems built into doors and windows. The Hole in the Wall Gang was led by Frank Cullotta, a childhood friend of Spilotro.

Details

STATE RESISTS ROSENTHAL LICENSING

Although Rosenthal was effectively running Glick’s Argent casinos, state gaming regulators were reluctant to grant him a license for the top position. Haunted by his past record as a sports fixer, Rosenthal was forced to hold lesser positions such as food and beverage manager and entertainment director.

Details

As part of Rosenthal’s campaign for licensing and legitimacy, he created and hosted a late-night television talk show. Aired locally in 1977 and 1978, the show featured entertainers and athletes as guests, including Frank Sinatra, Don Rickles, Burt Reynolds, O.J. Simpson and Tina Turner. Rosenthal also used the show to complain about state gaming regulators who refused to give him a license.

Details

Las Vegas defense attorney Oscar Goodman represented Frank Rosenthal and Tony Spilotro in all their dealings with state gaming regulators and criminal courts in the 1970s and ’80s. Goodman was a bold and effective advocate. He kept his clients out of jail, but he could not keep them out of Nevada’s Black Book, the list of individuals banned from the state’s casinos.

Details

In 1978, FBI wiretaps captured conversations indicating that Joe Blasko, a Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department detective, was tipping off mobster Tony Spilotro about law enforcement’s plans. Blasko even provided Spilotro with the identities of undercover agents and informants. Metro fired Blasko and his partner, Phil Leone. Leone retired, but Blasko went to work for Spilotro.

The Blasko revelations created a rift between Metro Police and the FBI, which lost confidence in the police department’s ability to keep a secret.

Details

LAW ENFORCEMENT RAMPS UP

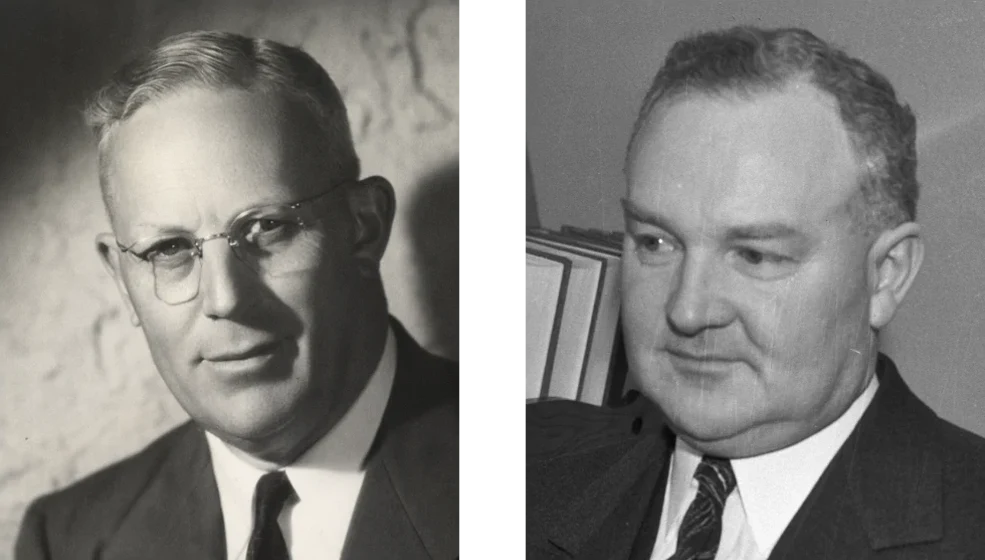

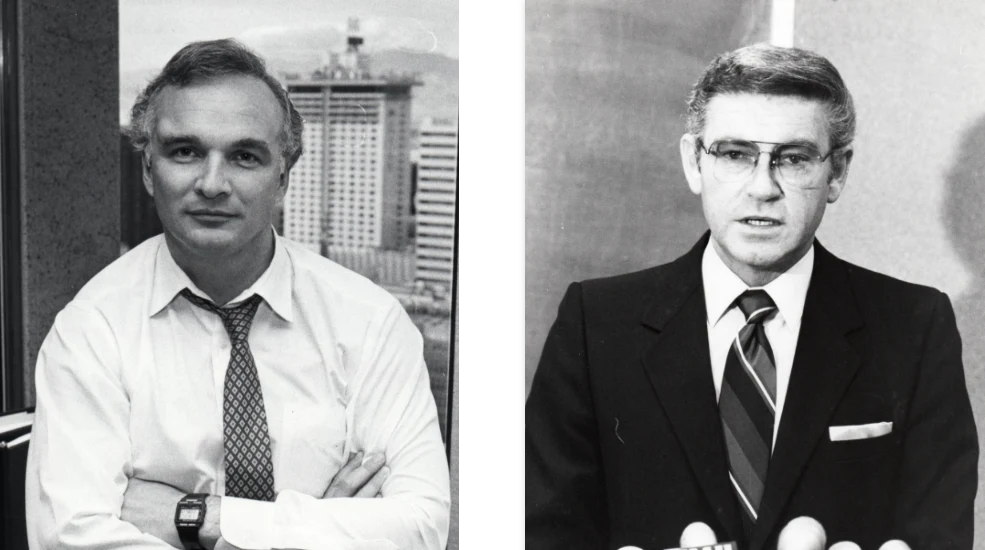

In the mid-1970s, Nevada Governor Mike O’Callaghan started hiring a new crop of gaming regulators who brought a more aggressive approach to exposing organized crime influence in the casino industry. His appointees included Shannon Bybee, Harry Reid and Jeff Silver.

Silver, a 29-year-old Gaming Control Board member, soon found himself interrogating Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal in a public hearing. Silver had unearthed extensive records of Rosenthal’s sports-fixing exploits in the 1960s.

Details

In the late 1970s, the FBI, Justice Department and Metro Police ramped up their efforts to investigate the Mob in Las Vegas.

The FBI first had to clean house. The Las Vegas Field Office’s agents had developed a reputation for accepting comps – free meals and shows – from local casinos. The agency brought in hard-charging Joe Yablonsky as its special agent in charge. Then it added agents Emmett Michaels, Charlie Parsons, Dennis Arnoldy and Gary Magnesen to target organized crime.

Details

Meanwhile, the Justice Department’s Organized Crime Strike Force added attorneys in Las Vegas to coordinate the investigations and prosecutions, including Geoffrey Anderson and Stan Hunterton.

Metro, under the new leadership of Sheriff John McCarthy, beefed up its organized crime squad, promoting Kent Clifford to Intelligence Bureau commander. Clifford assigned five officers to full-time duty investigating Tony Spilotro.

Details

In 1980, two of Clifford’s intelligence detectives, Gene Smith and Dave Groover, were surveilling Spilotro’s gang when they spotted a 1979 Lincoln with Illinois plates parking in front of the Upper Crust pizza parlor, owned by Spilotro associate Frank Cullotta. As the driver left the pizzeria, Smith and Groover followed him. The driver started speeding and driving recklessly. When they pulled him over, they suspected he had a gun. The detectives said that when the driver aimed the gun at them, they opened fire.

Details

The detectives killed Frank Bluestein, who was a Spilotro associate. A coroner’s jury ruled the shooting to be justified, but Bluestein’s family, as well as defense attorney Oscar Goodman, contended it was an excessive use of force. The family filed a civil lawsuit against the police department. The police department, represented by Las Vegas attorney Walt Cannon, won the case.

Details

The lawsuits, however, were the least of Smith and Groover’s worries. The FBI informed Intelligence Commander Kent Clifford that it had gathered credible information that the Chicago Outfit planned to take out the detectives who had shot Frank Bluestein.

Clifford and another officer flew to Chicago to confront the Mob bosses directly. They went to the homes of Joe Aiuppa, Joe Lombardo and Tony Accardo but none of them was home. They did meet with Allen Dorfman, the insurance broker who controlled the Teamsters Union pension fund.

After the Dorfman meeting, Clifford received a call that same afternoon from a lawyer representing the mobsters. Clifford told the lawyer, “If you kill my cops, I’ll bring 40 men back here and kill everything that moves, walks or crawls around the houses I visited today.” After delivering the message, the lawyer called Clifford back and assured him that his officers had nothing to worry about.

Details

MOB ON THE RUN

The Hole in the Wall Gang’s demise unfolded on July 4, 1981, when it tried to pull off its biggest heist to date. The gang planned to burglarize the Bertha’s Gifts & Home Furnishings on East Sahara Avenue, believing the store’s safe contained upwards of $1 million in jewelry and cash. But Spilotro, Cullotta and the other members of the burglary crew did not know that one of their own, Sal Romano, was a police informant.

FBI agents and Metro officers staked out Bertha’s and waited for the gang to gain entrance to the store through the roof. When that happened, they jumped into action and arrested the burglary crew.

Details

In 1982, Frank Cullotta was convicted of charges of possession of stolen property. He also was still facing a heavy sentence for the Bertha’s burglary. Then the FBI reached out to let him know that it had become aware that the Chicago Outfit wanted him dead. Cullotta decided to switch sides and become a government witness. In exchange for a shorter prison term, he entered the federal Witness Protection program and testified against his former partners.

Details

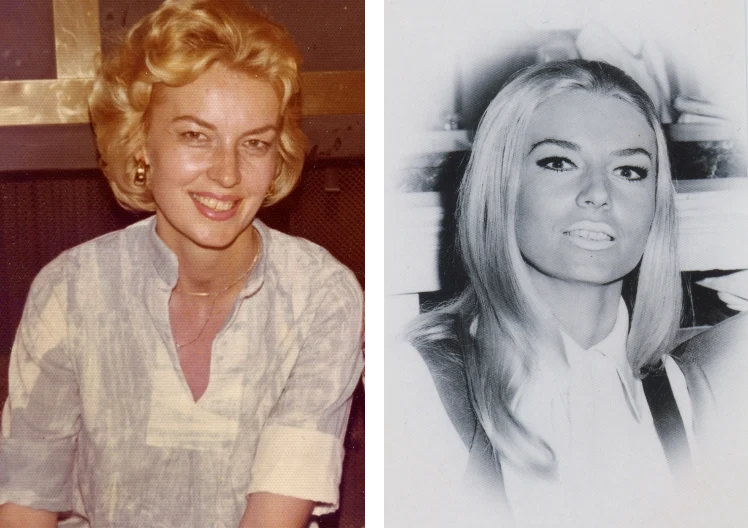

On October 4, 1982, Lefty Rosenthal left Tony Roma’s restaurant on East Sahara Avenue and got into his Cadillac Eldorado. When he turned the key in the ignition, the car exploded. C-4 explosives had been placed under the trunk next to the gas tank.

Rosenthal was lucky. His Cadillac came equipped with a steel plate under the driver’s seat that prevented him from feeling the full effects of the blast. He had time to climb out of the car before the gas tank exploded. He had cuts and bruises but no other injuries.

Details

Rosenthal left Las Vegas soon after the car bombing. He first moved to Orange County, California, and later to Florida, where he ran a bar and a sports betting website. Police investigated multiple potential suspects in the car bombing, but no one was ever arrested.

Details

Frank Rosenthal’s ex-wife, Geri, met an untimely end not long after the car bombing. Following her affair with Tony Spilotro and breakup with Frank, Geri moved to Los Angeles. On November 6, 1982, she collapsed on the floor of a Sunset Boulevard motel. She fell into a coma and died three days later at a hospital. The coroner said she died of an accidental drug overdose, but some, including the late Metro Commander Kent Clifford, suspected foul play.

Details

The FBI and Justice Department investigation of skimming in Las Vegas was known as Operation Strawman. The investigation, led by Strike Force prosecutor David Helfrey, resulted in two trials, known as Strawman I and Strawman II.

Details

Strawman I exposed the skim at the Tropicana Hotel, an operation led by the Kansas City Mafia. Bugs placed in a Kansas City house where mobsters met to discuss criminal business revealed the skim in detail. A search of Kansas City mobster Carl DeLuna’s house in 1979 turned up detailed written records of the skim operation. A 1983 trial resulted in seven convictions.

Details

Strawman II exposed the skim at the Argent casinos, an operation controlled by the Chicago Outfit. A 1985 trial resulted in convictions and guilty pleas for a number of high-profile Chicago mobsters, including Joey Aiuppa and Joey “The Clown” Lombardo.

Details

Details

THE AFTERMATH

In June of 1986, brothers Tony and Michael Spilotro went missing. Eight days later, their bodies were discovered buried in a shallow grave in an Indiana cornfield. Officials speculated at the time that the Spilotros had been beaten at the scene and perhaps buried alive. No suspects were arrested.

Details

During the Family Secrets trial in Chicago in 2007, testimony from Mob hit man Nick Calabrese revealed what actually happened to the Spilotro brothers. A large group of Chicago Outfit members beat them to death in the basement of a home in Bensenville, a Chicago suburb. Their bodies were transported to the Indiana cornfield and buried.

The Outfit bosses came to believe that Tony Spilotro had generated too much heat in Las Vegas and had to go. They took out his younger brother, too, to prevent him from exacting any sort of revenge.

Details

For years, people wondered why Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal was not indicted in the Strawman case. After all, he orchestrated the skim of millions of dollars from the Stardust and other casinos. In 2008, Las Vegas Review-Journal reporter Jane Ann Morrison, based on three former law enforcement sources, provided the answer: Rosenthal was an FBI informant.

Details

By the late 1980s, the traditional Mob had been rooted out of the Las Vegas casino industry. Entrepreneurs and corporations took center stage as the megaresort era began with the openings of The Mirage in 1989, the Excalibur in 1990 and the MGM Grand in 1993.

Details

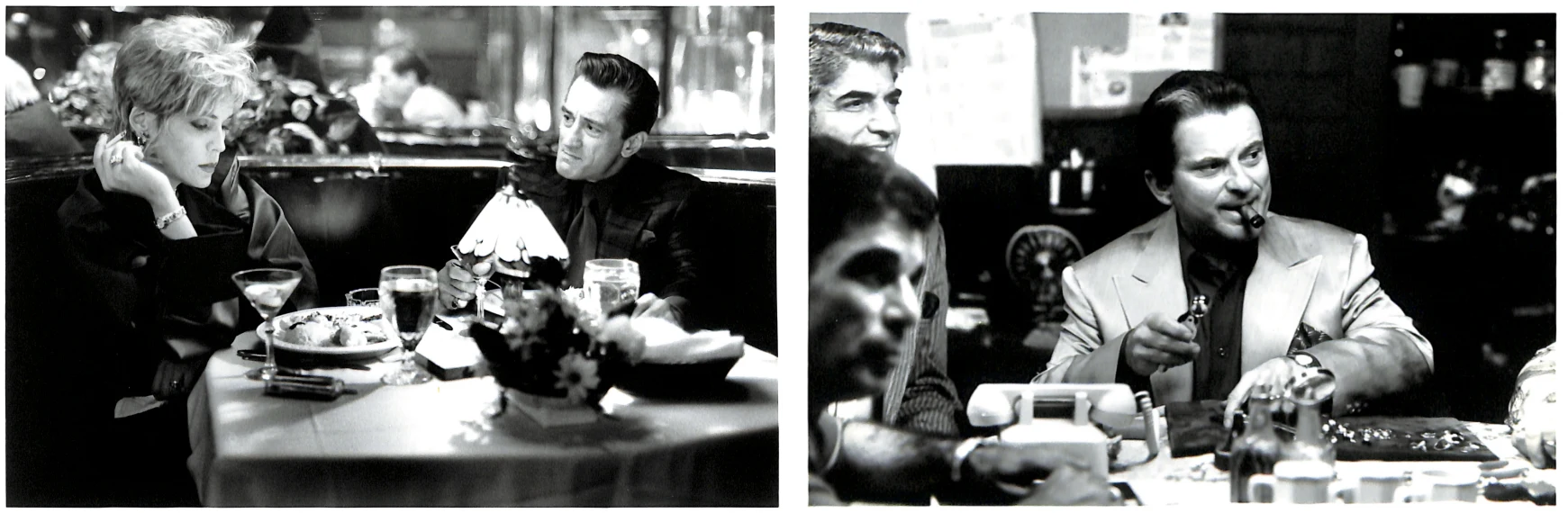

In 1995, Martin Scorsese released the movie Casino, starring Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Sharon Stone. The movie, co-written by Nicholas Pileggi, is a fictionalized depiction of the rise and fall of Lefty Rosenthal and Tony Spilotro in Las Vegas.

Details

Details

This exhibit received generous financial support from the Commission for the Las Vegas Centennial.

This project is funded by the sales of the Las Vegas License Plate.