Whitey in Hollywood

Two big-budget movies explore the late Boston mobster’s criminal exploits and role as an FBI informant

One of the most overtly symbolic scenes in Mob movie-making comes at the end of Martin Scorsese’s Oscar-winning film The Departed, when a rat scurries into view on a balcony railing, tarnishing the image of the historic gold-domed Massachusetts State House.

Corruption at the highest levels allows rats to thrive, this scene implies, undermining officialdom’s credibility.

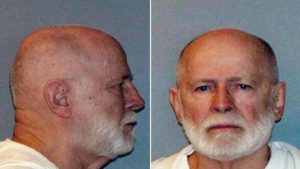

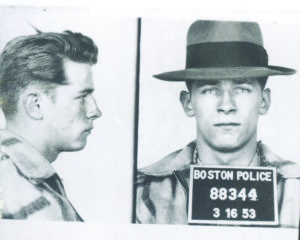

To many, the rat scene sums up not only the movie but also the life and death of James “Whitey” Bulger, an Irish-American gangster and FBI informant during his violent criminal reign in Boston. Nicknamed “Whitey” because of his hair color as a youth, Bulger preferred being called Jim.

Featuring Jack Nicholson in the lead role as a manipulative, evil character reminiscent of Bulger, The Departed is set in Boston and focuses on the law enforcement subculture of infiltrators and informants, with betrayal and corruption leading to deadly outcomes.

The 89-year-old Bulger’s recent murder in a federal penitentiary, and his lawless exploits with Boston’s Winter Hill Gang, play into the rat theme on obvious display in The Departed. In 2007, the movie won four Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director, a first for Scorsese.

Bulger’s recent death has sparked renewed interest in movies, documentaries and books about this government-protected killer from rough-and-tumble South Boston, or “Southie.”

In late October, Bulger was killed within 12 hours of his arrival at United States Penitentiary Hazleton in West Virginia, near the Maryland border. Weeks after the killing, a notice on the prison’s website still stated that visitation had been suspended. Two other inmates have been killed this year at the high-security facility of 1,262 male prisoners.

Bulger reportedly was transferred there because of disciplinary problems at a Florida prison where he had been serving two life terms plus five years in a gangland crime wave that included involvement in 11 murders from 1973 through 1985.

More than one inmate is believed to have been involved in beating Bulger to death in his wheelchair. One suspect is 51-year-old Folios “Freddy” Geas, a hit man from West Springfield, Massachusetts, serving a life sentence for the 2003 murder of a Genovese crime family leader in Springfield, the New York Times reported.

Bulger’s eyes apparently were dislodged from his head and he was beaten with a padlock-stuffed sock, according to an October 31 story in the Times. He was beaten to the point of being “unrecognizable,” an unnamed source told the newspaper.

Attorney Daniel D. Kelly, who has represented Geas, conceded the hit man has a “great disdain” for informants, but the attorney did not say Geas killed Bulger, according to the New York Post.

A funeral service for Bulger was held November 8 at St. Monica Church in South Boston. He was buried beside his parents at a cemetery in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, according to the Boston Globe.

Dick Lehr, author of Whitey: The Life of America’s Most Notorious Mob Boss, said Bulger “lived violently” and apparently died that way, too. “It marks the full circle of a terrible life,” Lehr, a professor and former Boston Globe reporter, told CNN.

With fellow journalist Gerald O’Neill, Lehr wrote the 2012 book Black Mass: Whitey Bulger, the FBI, and a Devil’s Deal. That book later was turned into the movie Black Mass, starring Johnny Depp as Bulger. The movie explores Bulger’s relationship with his politically powerful brother, William, who rose to the presidency of the Massachusetts state Senate, and John Connolly, an FBI agent later imprisoned on a murder conviction for his role as Bulger’s federal handler. The FBI gave Bulger protection in exchange for information on the Italian Mafia, or La Cosa Nostra, operating out of Boston’s North End.

In their 2011 film guide The Ultimate Book of Gangster Movies, George Anastasia and Glen Macnow wrote that Bulger was a “Top Echelon Informant” for the FBI, “the highest and most secret rank of federal snitch.”

“For years, he provided information about underworld rivals,” the authors wrote, “helping the feds make dozens of cases, most against traditional La Cosa Nostra gangsters. In exchange, two rogue FBI agents who were wined and dined by Bulger fed him the names of underworld figures who were providing law enforcement with information about him. Some of those people turned up dead.”

The FBI was so “crazed” about arresting high-profile Italian mobsters that it gave Bulger a long-term free run in Boston in exchange for information, according to public radio reporter David Boeri in the 2014 documentary film Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger.

“He was allowed to turn the Federal Bureau of Investigation into the Bulger Bureau of Investigation,” Boeri said.

Tipped to pending trouble, Bulger fled Boston in 1994. He remained at large for 16 years until his 2011 arrest 3,000 miles away in Santa Monica, a Southern California beach town where he had been living with his girlfriend in a rent-controlled apartment near the Third Street Promenade shopping district. Neighbors knew them as Charlie and Carol Gasko. From their apartment, authorities recovered more than $800,000 in cash and 30 guns hidden in holes in the walls. Also recovered were numerous true-crime books.

Bulger’s girlfriend, Catherine Greig, was sentenced to an eight-year prison term in 2012 for identity fraud and aiding and abetting a fugitive.

Until the end, Bulger insisted he was not a rat, saying he paid law enforcement officials as much as $50,000 for information but did not snitch. We’re paying; we’re not saying, was the explanation of his arrangement with federal authorities.

Following his arrest, Bulger said he’d had a secret immunity deal with U.S. Attorney Jeremiah O’Sullivan to protect each other after prosecutor O’Sullivan began to fear that Italian mobsters would seek revenge against him. O’Sullivan, who died in 2009, led the New England Organized Crime Strike Force from 1973 to 1989, during the height of Bulger’s power.

Some in authority don’t give credence to Bulger’s story, which he expressed after O’Sullivan had died, about a deal with the prosecutor. Burger concocted cover stories about his role in a face-saving effort not to be labeled a rat, his detractors say.

“He doesn’t mind being called a murderer,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney Fred Wyshak in the documentary film. “Obviously he doesn’t mind being called a drug dealer, but he doesn’t want to be called an informant because where he is from in Southie that’s the worst thing you can be.”

As in The Departed, the rat theme also pops up in the Black Mass film, including the opening scene in which Bulger associate Kevin Weeks, played by Jesse Plemons, says to a federal official recording his testimony: “Before we start, I want you to know something: I’m not a rat.” Weeks agrees to the term “government witness.”

After a prison stint, the real-life Weeks has collaborated with journalist Phyllis Karas on three books to date, including 2007’s Brutal: The Untold Story of My Life Inside Whitey Bulger’s Irish Mob.

In their film guide, Anastasia and Macnow wrote that the rat theme, at least in The Departed’s closing shot, was a bit much.

“It was unnecessary symbolism,” they write.

However, the authors are not excessively harsh in criticizing any aspect of the movie, including that final symbolic image. “It’s hard to find anything not to like” about The Departed, they write.

In the weeks following Bulger’s death, media coverage about his status as an informant has been extensive. In a recent interview on the late-night radio talk show Coast to Coast AM, author and journalist T.J. English said Bulger had delusions of grandeur, believing he could get away with murder. English wrote the 2015 book Where the Bodies Were Buried: Whitey Bulger and the World That Made Him.

English said Bulger, as an informant, was operating against an underworld code but had deluded himself about all that. “Believe it or not,” English said in the November 7 radio interview, “mobsters do have codes that they operate by — and not being a rat is definitely one of those codes.”

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. Henry taught journalism at Haas Hall Academy in Bentonville, Arkansas, and now is the headmaster at the school’s campus in Rogers, Arkansas. The Mob in Pop Culture blog appears monthly.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org