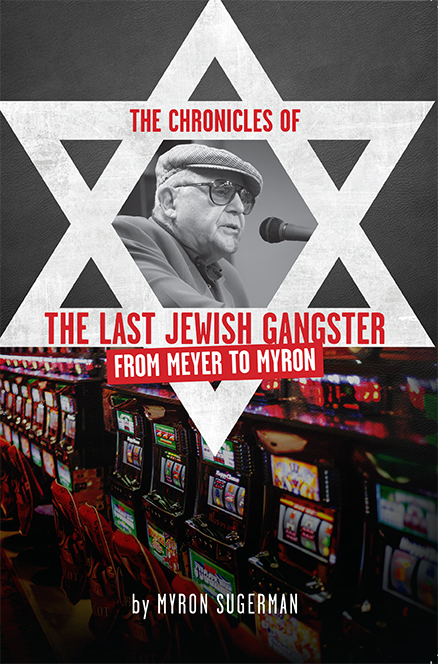

Excerpts from “The Chronicles of The Last Jewish Gangster” by Myron Sugerman

Sugerman to share his memories at November 9 event at The Mob Museum

The history of the Mob and the history of Jews in America are intertwined, and it’s a history that Myron Sugerman, author of the recently released book “The Last Jewish Gangster from Meyer to Myron,” traces from the earliest days of the Mafia to the present day. Sugerman tells the Mob story from a Jewish viewpoint, with stories gleaned from his firsthand experiences and family connections with some of the most infamous Jewish mobsters.

Enjoy a preview of what to expect at this program by reading an excerpt from Sugerman’s book below.

From Chapter 1 (pages 1 thru 3)

From Chapter 1 (pages 1 thru 3)

I was destined to go into this world. I loved it. I loved it from the first moment I was exposed as a kid. To be a part of my father’s world – jukeboxes, pinball machines, Bingo machines, and penny arcade games – was all I’d ever wanted since almost as far back as I can remember.

Like lots of Jewish old-timers from the Prohibition Era, my father Barney “Sugie” Sugerman made his living between the grey area between legal business and criminal activity. The company he founded in 1938 with Doc Stacher and Abe Green, the Runyon Sales Company, sold coin-operated machines – everything from jukeboxes to slot machines to pinball machines which back then were less innocent as you might think.

I was the architect that single-handedly revived the new gambling machine business in New Jersey and New York in the 1970s, a business that spread across the United States and abroad. I spoke the foreign languages of the many different ethnic groups in whose neighborhoods I did business…but more important, I was fluent in the language of the coin-operated machine industry and the lingua franca of the streets. I was baptized in these waters the day after my bris – the Jewish circumcision ceremony that takes place on the eighth day following the birth of a baby boy. And even before that, from the very moment of conception, while I was still in my mother’s womb, I was hearing the sound of gambling machines, saloons, gin mills, nightclubs, espresso houses and goulash joints.

I was born in Newark, New Jersey. As a kid growing up, even before my bar mitzvah, I used to polish the jukeboxes in Pop’s warehouse. When I got a little older I got involved a little deeper; at age 15 I was making collections from the jukeboxes Runyon owned that we’d placed and operated in bars all over Newark. In the Central Ward, the blacks called jukeboxes “piccolos,” and they called me “The Kid That Worked for the Piccolo Man.”

In June 1959, I graduated from Bucknell University with a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Languages, and that summer I started in the family business for real. No more polishing jukeboxes – Sugie had bigger plans for me.

Pop’s warehouse was filled with coin-operated machines, many of which were gambling machines, and some of which – the slot machines, for example – had been built especially for gambling. My idea was to become a major exporter; I went to work for Pop organizing an exporting business five days after graduating from Bucknell.

Pop was impressed with my enthusiasm for the business and decided to bet on me – so to speak. He bought me a ticket for Europe: first stop, Lisobn, Portugal. Dropping me off at Idlewild Airport (now JFK) with $3,000 worth of American Express traveler’s checks in my pocket, he told me to not come home until I’d emptied his warehouse.

I spent the next three months traveling through Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark and Holland. My first score was Hamburg, Germany. I was in the right place at the right time. I sold out the warehouse. In my innocence, I sent a cablegram home to Pop and told him to send me back an inventory and prices that I would have it for the following day when I was going to meet with the Geschaftsfuher of Helmut Rehbock GmbH in Hamburg. Pop sent me a cablegram and being unsure if he’d included reconditioning and packing, I added $200 more per machines, just to play it safe. The price was accepted for something like 100 machines, which created an extra $20,000 in profit. When I finally came home three months later, Sugie was at the airport with my mother and Sugie’s friend Herman Paster. I never saw such a big smile on his face. He asked me, “How’d you get $20,000 over the price?” I told him I wasn’t sure if he’d included reconditioning and wood crating. Obviously, he had!

I made especially good use of my time in Antwerp, Belgium. It was a free port, meaning you could ship goods through there without paying customs duties. On the tail end of that trip, I traveled to France and England.

In England, I was hosted by Herbie Katz – a chain-smoking gangster from New York who had a face that looked like a porcupine. Katz was a fugitive from American justice and married to a delightful Irish girl named Molly Malone. She deserved a Nobel Peace Prize for putting up with Mr. Katz. Herbie belonged to Tommy “Three Finger Brown” Lucchese. He was running slot machines illegally in Southampton when the British government legalized slot machines in 1959. Herbie liked it better when it was illegal. When I arrived in London from Southampton, Herbie was waiting for me at the train station. He took a look at me and said, “What am I? A babysitter for the Mob?” I was only 21 years old. My visit with Herbie Katz was more like one of public relations, because back home at Runyon’s offices on 221 Frelinghuysen Avenue in Newwark, Tommy Lucchese and Gerardo Catena, the two bosses, were entering into an agreement for Mickey Wichinsky in Las Vegas, who belonged to New Jersey. They were going to supply endless numbers of used Mills and Jennings slot machines to Herbie who would sell and be responsible to both enterprises. I was just a kid, fresh out of college, so this was a major deal being made between the powers-that-be, and I was just there to let Herbie babysit me by taking me into the different pubs of Southampton to see the “punters” lined up to pull on those one-armed bandits.

Even at the tender age of 21, I was good at the occupation Sugie had picked for me. Before I was through, I’d emptied the warehouse ten times over. But even as I was making my mark in my father’s world, big changes were brewing for Jewish gangers in Newark.

Copies of the book will be available for purchase at the November 9 event. Cash or check only.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org