‘Goodfellas’ still going strong after 30 years

A new book on Martin Scorsese’s classic Mob movie explores its legacy

In the painting, a man with white hair and beard, his left hand steering an outboard motor, is piloting a small boat through a narrow waterway. Two dogs are along for the ride in the open air.

One dog is looking one way. The other dog is looking the other way.

This painting hangs in screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi’s New York City apartment. His mother drew it from a picture in National Geographic magazine.

For 30 years, after being briefly displayed in Martin Scorsese’s 1990 movie Goodfellas, the painting has been popular among film fans. Scorsese’s own mother, Catherine, playing the parent of a volatile New York City mobster, shows the painting to her son and two of his underworld associates at the dinner table in her modest home. A near-dead victim is in the trunk of the gangsters’ car outside. Soon they will finish him off.

But first, the painting.

Looking at his mom’s artwork over an impromptu late dinner, Tommy (Joe Pesci), says, “I like this one. One dog goes one way, and the other dog goes the other way.”

“One is going east,” the mother says, “and the other one is going west. So what?”

The painting’s place in movie lore is a testament to Goodfellas’ continued popularity, as the film celebrates its 30th anniversary this month. Other memorable moments from the movie — the deadly “shine box” insult, the “funny how?” scene — also have become part of popular culture.

It wasn’t always this way.

Even with a major star like Robert De Niro in the film, Goodfellas was panned before it hit movie theaters. A California test audience gave it the worst preview grades in Warner Brothers’ history at the time, prompting the studio to consider recutting some of the violent scenes, according to The Ultimate Book of Gangster Movies by George Anastasia and Glen Macnow.

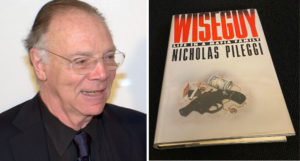

The movie, based on Pileggi’s 1985 true-crime book Wiseguy, ultimately was released without changes.

The book and movie focus on Henry Hill, who, beginning during his youth in Brooklyn, joined up with mobsters in his working-class neighborhood, later becoming a government informant and entering the Witness Protection Program. Christopher Serrone plays the young Henry Hill, while Ray Liotta portrays Hill as an adult.

Goodfellas did not win the Best Picture Oscar the year it was nominated. That went to Dances With Wolves, starring Kevin Costner. But since then, Goodfellas has taken off, ranked by many critics and fans with the first two Godfather movies as the best Mafia films of all time. In The Ultimate Book of Gangster Movies, the authors call Goodfellas “a brilliant movie packed with dozens of colorful characters.”

“Word of mouth and strong reviews helped it develop legs,” the authors note.

Though a lower-level Mob associate during much of his active criminal life, Hill, because of Pileggi’s book and the movie, became a well-known figure. Several other books since then have come out that Hill wrote with different authors, including a cookbook, a guide to Goodfellas-related locations in New York, and a book about his experiences in the Witness Protection Program.

“My life in the Mob made me famous,” Hill says in the 2004 book Gangsters and Goodfellas, written with Gus Russo, author of The Outfit and a Mob Museum Advisory Council member.

Hill, who died in 2012 at age 69, continues to generate interest. His paintings can be found for sale online, and new books about the world he lived in are still being released.

Some books focus less on Hill and more on one of the key parts of the movie’s plot, the December 1978 Lufthansa Airlines heist at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. (Hill supposedly was in Boston at the time of the heist, orchestrating a college basketball point-fixing scheme.)

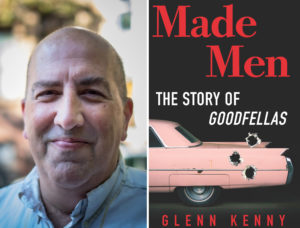

The Goodfellas mystique continues to grow. A book released this month, Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas, by film critic Glenn Kenny, examines in detail how the movie came together, exploring scene development, technical aspects and casting decisions. A postscript at the back of Made Men provides a summary of books in the “Goodfellas Library.”

In response to an email, Kenny, who writes for the New York Times and other outlets, said Goodfellas continues to be popular “because it’s so good.” He said the movie is “funny, harrowing, beautifully made, beautifully performed.”

“Despite the awful things the characters do, and a lot of their awful attitudes — their racism, homophobia, disregard for others, all that and more — Henry Hill and company are presented as real, three-dimensional people with ‘relatable’ aspects,” Kenny said in the email. “Some of the people in the movie you feel like you automatically know. Others you hope you will never meet!”

Kenny noted that the movie also has an “endless series of quotable scenes and bits, from ‘How am I funny?’ to Henry’s whine of ‘Karen!’ to Paulie’s ‘And now I gotta turn my back on you.’”

Scorsese, who has directed several movies with Mafia figures either in the forefront or on the periphery, including Mean Streets and Raging Bull, is one of the top two Mob movie directors in the industry, Kenny said.

“I still think the first two Godfather movies hold up well enough that I’d have to say that Scorsese and Coppola are tied as the best Mob movie directors ever,” he said in the email. “They both come from similar places — while Coppola wasn’t a New York fella, he has a similar family background to Scorsese, at least with respect to the Italian-American experience. Their roots give their observations and instincts a depth that no American directors looking at the Mob could ever hope for. And I think that the Godfather movies complement not only Goodfellas but also Mean Streets and Raging Bull. They’re unique, vivid pictures of times and ways of life that are gone forever but never stop gripping us.”

Kenny said Scorsese knows “more about filmmaking and films than almost any other director alive.”

A portion of Kenny’s book is devoted to the significance of music in Scorsese films. Pileggi, a veteran crime reporter who co-wrote not only Goodfellas but also a later Mob movie with Scorsese, Casino, agrees that music is extremely important to the veteran director. The 1995 film Casino also is based on a Pileggi true-crime book, Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas.

Over the telephone from his apartment in New York City, Pileggi said that when he and Scorsese were working on the script for Goodfellas, “Marty already had a vision of the music in his head.”

As an example, Pileggi said that as he was typing a scene in which the De Niro character, Jimmy, is at a bar smoking a cigarette and contemplating whether a character named Morrie should be killed, Scorsese turned to Pileggi and told him to type in the word “cream.” This ended up being the place in the movie where the song “Sunshine of Your Love” by the 1960s British rock band Cream loudly comes in.

During interviews, Scorsese has stressed the importance of music in his movies. “Probably the most enjoyable part of making movies is to select these songs,” Scorsese told The New York Times. Kenny uses this quote, with the attribution, in his book.

Speaking on the phone about Goodfellas, Pileggi said, “The music is practically another character.”

Pileggi said an additional aspect that works in Goodfellas’ favor is that many of the scenes are short, providing a fast “bam, bam, bam” effect. There are no long scenes to challenge anyone’s attention span, he said.

Whether directed by Scorsese or other filmmakers, Mob movies continue to be popular. Kenny said part of the reason is that “law-abiding citizens all have a secret side that wants to know what it’s like to be on the other side of life — to transgress, to break the rules, to take what they want however they want it and not worry about the consequences.”

“In crime movies they can do that vicariously,” he said in the email.

Kenny added that these movies also are appealing because of “the power aspect.”

“Goodfellas is what it’s about to be a Mob foot soldier, but it makes you wonder about the underboss Paulie — his quiet way of leadership. That’s fascinating,” Kenny said. “Even though they do evil, cowardly things, Mob figures are mythic and larger than life to some people, exactly because they live on the edge of what society deems acceptable. Everybody wonders what it’s like to be bad. Movies about criminals and crime let you find out without putting yourself in danger — physical or moral!”

As for Goodfellas, its continued popularity shows up in the way fans remember famous lines or props — like the dogs in the painting looking in opposite directions.

Pileggi said the painting, now hanging above his desk, is in his will, to be handed down to stepson Max Bernstein, a musician. Bernstein is the son of journalist and filmmaker Nora Ephron and her then-husband Carl Bernstein, the former Washington Post reporter of Watergate fame. Pileggi was married to Ephron for more than 20 years until she died in 2012 at age 71. Among the many movies she had a hand in as director or screenwriter is My Blue Heaven, starring Steve Martin and based in part on Hill’s experiences in the Witness Protection Program. Ephron wrote the screenplay for My Blue Heaven, which came out only weeks before Goodfellas.

While the dogs painting has fans among the general public, a lot of family pride is invested in Mrs. Pileggi’s artistic contribution to the movie. As Nicholas Pileggi noted on the phone, the final credit in Goodfellas is to his mother, Susan Pileggi. She got a kick out of telling people about it, Pileggi said, and in asking them, “Have you seen my movie?”

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org