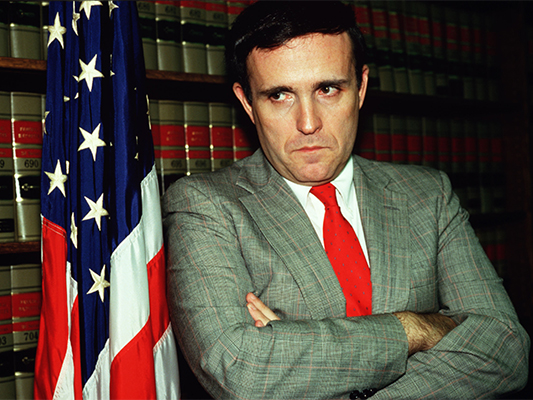

Rudolph Giuliani

Born: May 28, 1944, Brooklyn, New York

Nickname: Rudy

In 1989, when Rudolph Giuliani stepped down after six years as U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, he was perhaps the most famous law enforcement official in the United States. He left a legacy of successful prosecutions of leaders of New York’s “Commission” of organized crime families, the Mafia’s international heroin and cocaine ring in the “Pizza Connection” case, as well as high-profile political corruption and Wall Street criminal cases.

As mayor of New York for eight years, Giuliani made sweeping changes to law enforcement policies that reduced crime in the city by more than 50 percent and calmly shepherded the city and nation through the catastrophic 9/11 terrorist attacks that destroyed the World Trade Center.

Giuliani was born in Brooklyn to parents who were the children of Italian immigrants. He grew up with a father who reviled ethnic Italians who tarnished their community by turning to organized crime. His father noticed that there were no federal judges of Italian extraction in New York in the mid-1960s and encouraged his son to enter law enforcement. The younger Giuliani graduated from Manhattan College and later, right out of New York University’s law school in 1970, landed a job as an assistant U.S. attorney in the city’s Southern District. By age 30, he was the office’s third-highest-ranking prosecutor.

One of the federal cases Giuliani prosecuted in the 1970s came after he and his colleagues convinced New York Police detective Robert Leuci to work undercover within the force to report back about police corruption. Leuci’s story was told by Robert Daley in the nonfiction book Prince of the City that later became an acclaimed 2001 movie by the same name. Fifty-two New York cops were indicted on corruption-related allegations based on the evidence. Giuliani also won a conviction against Brooklyn area U.S. Congressman Bertram Podell, a Democrat who served several months in federal prison for accepting a $41,000 bribe.

Giuliani’s star rose. A recommendation from a federal judge he clerked for in law school got him in as assistant to President Gerald Ford’s Attorney General Harold Tyler in 1975. After Ford lost the presidential election to Jimmy Carter, a Democrat, in 1976, Tyler took Giuliani in as a partner in a corporate firm in Manhattan. Giuliani stayed there until 1981 after GOP presidential candidate Ronald Reagan defeated Carter. Giuliani changed his party affiliation from Democrat to Republican and through contacts was appointed associate attorney general, the third-highest spot in the Justice Department, under William French Smith. Giuliani’s next big step was becoming U.S. attorney for the Southern District two years later in June 1983.

Giuliani announced that his top priority as U.S. attorney was to defeat organized crime in New York, where the chiefs of the so-called “Five Families” lived and operated. He read Mob boss Joseph Bonanno’s 1983 memoir A Man of Honor, in which Bonanno described meetings with bosses of the other four families — Colombo, Gambino, Genovese and Lucchese — a national ruling body referred to as “the Commission.” The Commission, going back to 1931, met secretly to settle differences, consider new members, approve murders and dole out money earned through racketeering. Giuliani received permission from Washington to pursue a case against the Commission. By 1984, 350 FBI agents and 100 New York Police detectives were investigating the Mob. At the time, an estimated 1,000 “made” men and 5,000 Mob associates lived in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and elsewhere.

Giuliani’s probe included the placement of court-allowed recording devices in 1984 in places such as the Palma Boys Social Club in New York, where Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno held court, Paul Castellano’s home on Staten Island, an automobile used by a Colombo family member and a Jaguar car used by Lucchese family associate Sal Avellino to chauffeur various mobsters. From hundreds of hours of recorded conversations, investigators heard the gangsters talk about the Commission, narcotics sales and the contract murder of Bonanno figure Carmine Galante in 1979.

Giuliani decided to prosecute the leaders of the families and their upper-level cohorts together under the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, for allegedly conspiring to commit felonies including contract murders, loan sharking, extortion, labor racketeering and drug trafficking. It was the first time RICO, passed by Congress in 1970, was employed to prosecute a major federal case.

He argued the case before a federal grand jury and in February 1985 obtained indictments against a laundry list of New York’s Mob leaders and their lieutenants: Bonanno family boss Phil Rastelli and capo Anthony Indelicato; Colombo boss Carmine Persico and member Ralph Scopo; Gambino boss Paul Castellano; Genovese boss Anthony Salerno and member Gennaro Langella; Lucchese boss Anthony Corallo, underboss Salvatore Santoro and consigliere Christopher Furnari. Soon afterward, Castellano was shot and killed outside a restaurant in Manhattan and Rastelli was tried in a separate RICO case.

Giuliani assigned federal prosecutor Michael Chertoff to take the Commission case to trial. The government called 207 witnesses. Giuliani arranged for his star witnesses, Cleveland Mob underboss Angelo Lonardo, to testify, then the highest-ranking mobster to agree to serve as a witness. The case brought to light the Concrete Club, a scheme where Castellano and other mobsters demanded and received kickbacks on the cost of cement for building projects in New York in exchange for peace from Mob-controlled labor unions. In November 1986, the mobster defendants – including family leaders Salerno, Persico and Corallo – were convicted in the 21-count indictment and made to serve sentences of 40 to 100 years in prison, a crippling blow to the decades-old New York Mafia.

Giuliani also won racketeering indictments in 1986, during the Commission trial, in a separate case against Salerno and mobsters Vincent Cafaro, John Tronolone and Milton Rockman. The grand jury alleged that Genovese boss Salerno and the others conspired to engineer the selection of Jackie Presser for president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters in 1983 to control him and obtain union loans and jobs. Lonardo testified in the case, saying that he and Rockman met with Mob leaders in Chicago and with Salerno in New York to gather support for putting Presser in as head of the Teamsters. He also stated that the Mafia had controlled induction of the previous Teamsters president, Roy Williams.

This time, the jury acquitted Salerno and the others of rigging Teamster elections for Presser and Williams. Meanwhile, in May 1988, Giuliani’s office got guilty verdicts on Salerno, Genovese family member Matthew Ianniello and two others in a RICO case alleging extortion, union fraud and rigging bids for $30 million in cement work at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in New York.

The following month, Giuliani filed suit in New York to force the Teamsters to hold free elections and institute other reforms to eliminate organized crime influence in its locals. “The government’s complaint alleges that organized crime has deprived union members of their rights through a pattern of racketeering that includes 20 murders, a number of shootings, bombings, beatings, a campaign of fear, extortion and theft,” Giuliani stated.

In October 1988, a federal judge sentenced Salerno, who was already serving a 100-year sentence in the 1986 Commission case, to an additional 70 years for his conviction in the Javits center bid-rigging.

Another major Mafia case that came to Giuliani’s office was the famous “Pizza Connection” caper, in which the former chief of the Sicilian Mafia, Gaetano Badalamenti, and Bonanno crime family member Salvatore Catalano were charged as leaders of a $1.6 billion international heroin and cocaine smuggling and sales operation using pizza restaurants in New York as fronts since 1979. The 18 defendants were convicted in 1987. “It is a tremendous victory in the effort to crush the Mafia,” Giuliani stated in the Washington Post. “Five years ago nobody would have thought it possible to convict the head of the Sicilian Mafia and the head of a major part of an American Mafia family. The impact on the Mafia of these cases has been devastating. If this continues, there’s not going to be a Mafia.”

Before leaving office in January 1989, Giuliani also successfully prosecuted cases of alleged illegal insider trading on Wall Street and corruption in New York political circles. In 1987, Ivan Boesky, a Wall Street arbitrager who amassed $200 million investing in companies about to be taken over or bought out, was convicted of conspiring to file false documents, served two years in prison and was fined $100 million. In 1988, Giuliani then focused on a Boesky associate, Michael Milken, known as the “king” of selling unsecured “junk” bonds to raise funds for businesses. Milken was indicted on 98 counts including racketeering, insider trading and securities fraud, went to prison for nearly two years and paid $900 million in fines. Giuliani prosecuted and won racketeering convictions against Bronx Democratic leader Stanley Freidman and others in a bribery scheme involving the city’s parking meter violations agency. In 1988, four executives of the defense contractor firm Wedtech pleaded guilty to federal charges filed by Giuliani in illegal payoffs to public officials in exchange for no-bid contracts. The case also ended with the conviction of Congressman Mario Biaggi, a New York Democrat, for extorting payoffs from Wedtech.

His years as a “Mob buster” over, Giuliani entered electoral politics and ran for mayor of New York in 1989. He won the Republican nomination but narrowly lost to Democrat David Dinkins in the general election. Giuliani worked as a private attorney and ran for mayor again in 1993, defeating Dinkins. He won re-election in 1997.

While mayor, Giuliani sought to reduce crime in a city regarded as the nation’s crime capital. He implemented a “broken windows” policy: a no-tolerance stance toward petty crimes such as vandalism and panhandling. His administration is credited with reducing serious crime in New York by 56 percent during his eight years in office, including a 66 percent drop in murders and 70 percent decline in shootings. He ordered police sweeps to rid low-level drug dealers from Lower Manhattan.

In September 2001, in the final three months of his last term, Giuliani became the national face of New York after terrorists flew airliners into the World Trade Center’s iconic Twin Towers, causing both skyscrapers to collapse and killing nearly 3,000 people. Giuliani visited the site, kept residents informed regularly about rescue efforts as hope for the missing dwindled with each day and vowed that the city would rebuild and not be intimidated by terrorists. Time magazine selected him as its Person of the Year for 2001.