Journalist tracks history of New York Mafia

Selwyn Raab, author of classic "Five Families," to speak at Mob Museum

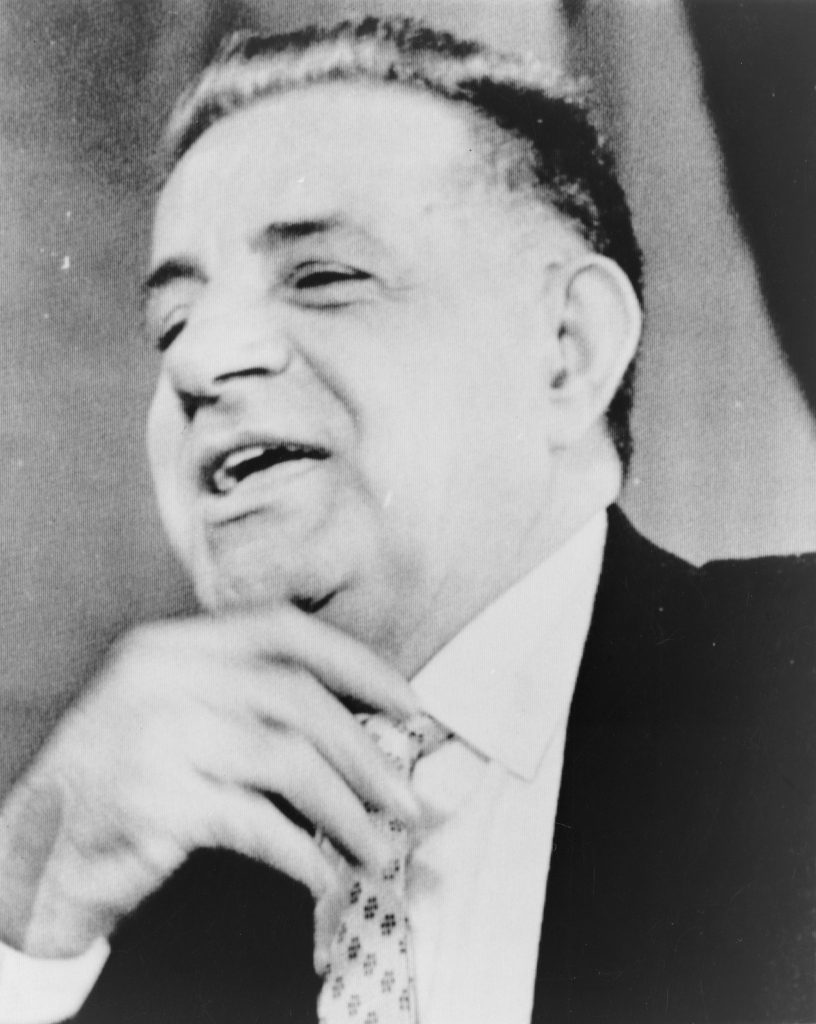

In the summer of 1963, Joseph Valachi, longtime Mafia soldier involved in more than a score of gangland killings for New York’s Genovese crime family, was serving a 20-year sentence in the Atlanta Penitentiary for narcotics trafficking. Valachi feared that crime boss and fellow inmate Vito Genovese had marked him for death inside the prison. On June 22 of that year, Valachi mistook an inmate for a Genovese enforcer and beat the man to death with an iron pipe. Now facing a murder charge, Valachi contacted U.S. authorities and offered to tell all about the vortex of America’s organized crime structure.

During an interrogation, FBI agent James P. Flynn asked Valachi about the Italian words “cosa” and “nostra” that agents had overheard organized crime figures use, and whether Valachi’s people referred to themselves as the “Mafia.”

“It’s not Mafia,” Valachi said. “That’s the expression the outsiders uses [sic].”

As recounted by Selwyn Rabb in his book Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires, that fateful conversation confirmed the secret term used for decades by Italian-American crime families in New York and beyond. When Flynn said that he knew the first part was “cosa” – Italian for “our” – Valachi took the bait.

“‘Cosa Nostra,’” Valachi said, naming the Mafia insider term for “our thing.” “So you know about it.”

That October, Valachi testified about Cosa Nostra (what the FBI would dub “La Cosa Nostra,” or LCN) on national television before the U.S. Senate’s McClellan Committee in Washington, D.C. His bold statements and revelations about the Mafia’s five families based in New York, though not always accurate, engaged the American public and provided a remarkable summary of the daily lives of members of the nation’s top crime families. As Raab writes, Valachi was “the first ‘made’ man to shatter the oath of omerta and provide accurate details about the Mafia’s customs and codes of behavior.”

Raab, whose 785-page book provides the most authoritative history of New York’s Bonanno, Columbo, Gambino, Genovese and Lucchese crime families from their roots in Sicily in the 1800s to the present day, will speak at the Mob Museum at 7 p.m. Thursday, November 17. The event is free with Museum admission.

Raab’s background in journalism goes back half a century, including as a newspaper reporter for the Bridgeport Herald, Newark Star-Ledger, New York World Telegram and New York Times, as news editor for WNBC-TV in New York and as executive producer for the PBS affiliate WNET-TV.

In Five Families, Raab traces the origins of each of the city’s crime clans to 1931, when Charles “Lucky” Luciano, the founder of the Genovese family, established the Mafia’s governing council, known as the Commission. That year, Luciano was fresh from arranging hits on two old-school Sicilian immigrant bosses within five months — first Joe Masseria and then Masseria’s successor, Salvatore Maranzano. To his Mafia cohorts in New York, Luciano claimed he acted in self-defense, as both Masseria and Maranzano were known to have plotted against him. He convinced Maranzano’s deputy, Joe Bonanno, and others that an alliance would avoid further gangland bloodshed. Luciano and Bonanno met with other bosses and united the five New York families.

Luciano and the Big Apple bosses then traveled to Chicago to meet with representatives of more than 20 Mafia groups from across the country. His new Commission operated like a corporate board, setting rules and settling disputes and problems by majority vote. The new organization also welcomed southern Italians such as Al Capone of Chicago to serve as bosses. While Luciano persuaded them it no longer made sense to install a “boss of bosses,” Commission members acknowledged Luciano as their unofficial leader. He separated the American Mafia from the Sicilian one, allowing the Commission to act independently inside its own country. But Luciano, Raab writes, by designating all five New York families as members of the Commission, “clearly defin[ed] New York’s keystone position in the Mafia’s national pecking order.”

“The five families would survive, under various names and leaders, into the next century,” Raab writes. “No other American city would have more than one Mafia family, nor would any other borgata [family] come close to matching the size, wealth, power, and influence of any of the New York families.”

The first edition of Raab’s book came out in 2005, and this year, in a new edition, he has added a epilogue detailing the latest activities of America’s Mafia families. Most of the gangs in major cities such as Detroit, Cleveland, Kansas City, Miami and Los Angeles have “been virtually eliminated or weakened to the level of a handful of elderly ‘has-beens’” but [r]emarkably, the Mafia’s venerable and strongest families survived in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other pockets of the Northeast.”

In New York, “current bosses and their soldiers are seemingly sustained by time-honored bread-and-butter rackets: illegal gambling; loan sharking; drug trafficking; and extortion of restaurants, nightclubs and businesses,” he writes.

And, Raab notes, the Sicilians are back, with the Gambino family basically led by immigrants from Sicily, known as “Zips,” with ties to organized crime families based in Sicily. Unlike previous Mafia gangs that considered the relatives of its members as off limits, the Zips are known to threaten — and to kill — family members of prospective “squealers” or defectors. However, today, according to law enforcement estimates, only about 700 to 800 “made” men exist compared with a high of 1,000 in the 1980s.

“The Genovese and Gambino borgatas, as they have since the formation of the American Mafia in the early 1930s, remain the nation’s largest and most potent gangs, each with more than a hundred soldiers,” the author writes.

“The Mob may attract new recruits, but experts are betting that a brain drain will eventually undermine the existing ranks. Demographics have eliminated large Italian-American neighborhoods in cities where, for generations, the Mafia lifestyle of huge profits and respect attracted a steady supply of eager applicants.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org